Research Article

Through the Students’ Lens: Photographic Methods for

Research in Library Spaces

Shailoo Bedi

Director, Academic Commons

& Strategic Assessment

University of Victoria

Libraries

University of Victoria

Victoria, British Columbia,

Canada

Email: shailoo@uvic.ca

Jenaya Webb

Public Services and Research

Librarian

Ontario Institute for

Studies in Education (OISE) Library

University of Toronto

Libraries

University of Toronto

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: jenaya.webb@utoronto.ca

Received: 15 Jan. 2017 Accepted:

29 Apr. 2017

![]() 2017 Bedi and

Webb.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Bedi and

Webb.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

–

As librarians and researchers, we are deeply curious about how our library

users navigate and experience our library spaces. Although we have some data

about users’ experiences and wayfinding strategies at our libraries, including

anecdotal evidence, statistics, surveys, and focus group discussions, we lacked

more in-depth information that reflected students’ real-time experiences as

they move through our library spaces. Our objective is to address that gap by

using photographic methods for studying library spaces.

Methods

–

We present two studies conducted in two academic libraries that used

participant-driven photo-elicitation (PDPE) methods. Described simply,

photo-elicitation methods involve the use of photographs as discussion prompts

in interviews. In both studies presented here, we asked participants to take

photographs that reflected their experiences using and navigating our library

spaces. We then met with participants for an interview using their photos as

prompts to discuss their experiences.

Results

–

Our analysis of students’ photos and interviews provided rich descriptions of

student experiences in library spaces. This analysis resulted in new insights

into the ways that students navigate the library as well as the ways that

signage, furniture, technology, and artwork in the library can shape student

experiences in library spaces. The results have proven productive in generating

answers to our research questions and supporting practical improvements to our

libraries. Additionally, when comparing the results from our two studies we

identified the importance of detailed spatial references for understanding

student experiences in library spaces, which has implications beyond our

institutions.

Conclusion

–

We found that photographic methods were very productive in helping us to

understand library users’ experiences and supporting decision-making related to

library spaces. In addition, engaging with students and hearing their

interpretations and stories about the photographs they created enhanced our

research understandings of student experiences and needs in new and unique

ways.

Introduction

Students’ images can elicit stories that

are not easily captured through other research methods. They can generate rich

descriptions of library spaces and reveal new and important insights into the

ways our users experience, navigate, and perceive the library. However, when

planning changes and improvements to library spaces or services, librarians

often rely on methods such as surveys or focus groups to seek input from users.

As Halpern, Eaker, Jackson, & Bouquin

(2015) note, “over-reliance on the survey method is limiting the types of

questions we are asking, and thus, the answers we can obtain” (p. 1). Although

surveys and focus groups are valuable for many types of research, they are

limited in providing "in the moment,” experiential data about how students

use our library spaces. In surveys and focus groups, students may be asked to

recall their perceptions or provide hindsight thinking about their experiences

with library spaces, services, or resources. However, when equipped with

cameras students can photographically document their experiences in a library

space as they move through it. The exercise of collecting images and discussing

them during follow-up interviews allows for deeper consideration of the

perceptions and experiences of being in a particular library space.

Over the past couple

of decades, many libraries have focused

their efforts on becoming user-centered, dynamic learning environments

developed to support student success. This change in focus has rendered much

discussion in the library and information science (LIS) literature about the

library as the “third place” (Ferria et

al., 2017; Harris, 2007; Montgomery & Miller, 2011). Authors often point

out that despite the proliferation of online resources the library’s physical

space is still critical to our users (Brown & Lippincott, 2003; Harris,

2007; Montgomery & Miller, 2011). Thus, continued exploration into library

user experience of library space, design, and wayfinding is worthy of

attention.

We propose that visual research methods,

specifically photographic methods, have a much larger role to play in

describing, interpreting, and understanding library users’ experiences.

Although visual research methods remain underrepresented in the LIS literature,

there are a few compelling examples that demonstrate great promise for LIS

research, especially for research focused on physical library spaces and the

student experience. Moreover, visual research methods offer valuable evidence

for decision-making and user-focused improvements to library space and design.

In

this article we present two studies that use visual research methods. The first

uses participant-driven photo-elicitation (PDPE) to understand users’

wayfinding strategies at the University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for

Studies in Education (OISE) Library, with the added goal of making user-focused

improvements to directories and signage. The second explores students’

experience in the library spaces at the University of Victoria using

photo-narrative as a way of guiding decisions for upcoming renovations and to

understand the student experience in library space. In addition to focusing on

questions in our immediate institutional contexts, we also make the broader

argument that students’ experiences with

the library are interwoven with the spaces and objects they encounter, and that

visual methods, and photographic methods

in particular, can reveal new and important insights into the ways library

users experience, navigate, and perceive library spaces.

Literature Review

Visual

methods are well established across the social sciences

and encompass a wide range of approaches, techniques, and types of images.

Among many other purposes, they can be used as a way for researchers to

document social processes (Hartel & Thomson,

2011), as part of ethnographic approaches to elicit information from

participants (Foster & Gibbons,

2007), or as a way to engage and empower communities

(Julien, Given, & Opryshko, 2013). Pollak (2017) provides a summary of visual methods used in

the social sciences and argues visual approaches are well suited to LIS

researchers “exploring information worlds filled with vagueness, contradiction,

fluidity, and movement” (p.105). The literature on visual methods is vast, but

Weber (2008) offers a comprehensive summary list of reasons to use images in

research

- Images can be used to capture the ineffable,

the hard-to-put-into-words.

- Images

can make us pay attention to things in new ways.

- Images

are likely to be memorable.

- Images

can be used to communicate more holistically, incorporating multiple

layers, and evoking stories or questions.

- Images

can enhance empathic understanding and generalizability.

- Through

metaphor and symbol, artistic images can carry theory elegantly and

eloquently.

- Images

encourage embodied knowledge.

- Images

can be more accessible than most forms of academic discourse.

- Images

can facilitate reflexivity in research design.

- Images

provoke action for social justice. (p. 44)

Visual research methods have slowly begun to gain

ground as part of a move toward more holistic approaches to studying libraries

and library users. The groundbreaking ethnographic project, Studying Students: The Undergraduate

Research Project at the University of Rochester, led by Foster and Gibbons

(2007), employed a wide range of methods including visual methods in which

students produced photographs, maps, and drawings as part of the research

process. Briden (2007) discusses the Rochester

project’s use of photo-elicitation interviews as a way to have students share

“details about their lives in a way that conventional interviews alone could

not achieve” (p.47). Researchers put cameras in the hands of participants and

provided them with a list of 20 photo prompts such as “All the stuff you take

to class”, “Your favorite place to study”, and “Your favorite part of the day”

(p. 41). The resulting images, in conjunction with interviews,

brought together a vivid description of students’ lives at the University of

Rochester, and helped shed light on how the library factored into the total

student experience.

More recent examples of visual methods applied in library contexts

also show significant promise for providing new insights into our users’

experiences (Haberl & Wortman, 2012;

Julien, Given, & Opryshko, 2013; Lin & Chiu,

2012; Neurohr & Bailey, 2016; Newcomer, Lindahl,

& Harriman, 2016; Treadwell, Binder,

& Tagge, 2012). Furthermore,

these studies point to the constructive, user-centered input that visual methods can provide for

making improvements to library spaces and services. For example, Newcomer et

al. (2016) used photo-elicitation as part of a broader ethnographic project to

solicit student input on the design of a new arts campus at their institution.

In their conclusion they highlight the value of ethnographic approaches for

gathering unexpected data from user populations, and note that the results of

their study have already been used to inform planning for the new arts campus.

There are many

considerations in using photographs in research, one of the primary ones being

that photographs are not neutral; they are contextual, intentional products. By

using photographs in conjunction with interviews in methods such as

photo-elicitation and photo-narrative, researchers can investigate these

complexities and understand the photographer’s intentions. Narrating through an image means storytelling

about things and experiences related to what has been photographed; it does not

mean telling or describing only what can be seen in a picture (Collier, 2001;

Pink, 2001). The photo by itself is not an independent data point or an

objective representation of data. Rather the photo is an interpretation of the

creators’ subjective experience (Liebenberg, 2009). The process of photographic

research methods, such as photo-narrative or photo-elicitation, goes beyond

describing each photograph taken by the participant, and includes an interview

that incorporates questions about what it is we are seeing, and what it is that

we are not seeing and why. Questions

about what was happening before and after a given photo are also critical to

understanding the contextual details (Liebenberg, 2009; Pink, 2001).

Ultimately, photographs can be thought of as a starting point in

photo-elicitation. As Weber (2008) writes, photographs and other artworks

“provide a versatile and moveable scaffolding for the telling of life history,

life events, life material” (p.48).

Aims

As librarians and researchers, we wanted

to know more about how our library users experience our library spaces.

Although we had data from our own libraries about space use and wayfinding

gained through anecdotal evidence and assessment instruments like statistics,

surveys, and focus group discussions, we recognized that we were missing more

in-depth research information that reflected specific and “in the moment”

student experiences in our spaces. As a result, the aim of both studies presented here is to

gather data that provides detailed and in-depth knowledge about user

experiences in our library spaces.

The overarching research question that

frames the two studies is: how do students use and navigate our library spaces?

While both projects have

goals for local service improvements, this work will also contribute to the LIS

literature by expanding our understanding of how students’ experiences within

the library are tightly interwoven with the spaces and objects they encounter

during their visits. By examining and comparing the use of photographic methods

in two independent studies and argue that photographic methods have broad

applicability for researchers interested in library space and design.

Methods

The studies we

present in this article use two types of photo-elicitation methods to examine

student experiences in library spaces. Described simply, photo-elicitation

involves the use of photographic data to provide discussion stimuli in

interviews. The photos used in the interview can be photos taken or collected

by the researcher, but more commonly, are photographs taken by the research

participants themselves that are then later discussed in the photo-elicitation

interview. This method is often referred to as participant-driven

photo-elicitation (PDPE). The studies presented here both use forms of PDPE

where research participants took the photographs used in the research.

In her summary of the literature, Rose (2012) identifies

four main strengths of photo-elicitation interviews:

- Photo-elicitation interviews evoke different information than other

social science techniques. In other words, “things are talked about in

these sorts of interviews that don’t get discussed in talk-only

interviews” (p. 305).

- Photographs can be helpful in shedding light on the more mundane or

day-to-day activities of participants’ lives. Having research participants

take photographs and then discuss them in interviews, gives participants a

“distance from what they are usually immersed in and allows them to articulate

thought and feelings that usually remain implicit” (p. 306).

- PDPE gives participants more power in the research process. Putting

research participants in charge of making photographs, rather than simply

answering a researcher’s questions, “gives them [participants] a clear and

central role in the research process” (p. 306).

- Photo-elicitation also facilitates collaboration between the researcher and participants that

other methods do not.

By using

photo-elicitation, we sought to gain new insights into students’ day-to-day

experiences in library spaces. Moreover, we hoped to engage in a more

user-driven type of research. The particular adaptations of photo-elicitation

applied in each situation, and the research instruments used, are described

below.

OISE Library,

University of Toronto

Context

The OISE Library’s Wayfinding Study was designed to

gain insight into the challenges and successes that users face when navigating

the OISE Library space. The OISE Library is 1 of 44 libraries in the University

of Toronto Libraries system, with collections and services that support

graduate students and faculty in the field of education. The library houses a

main stacks collection and several special collections, including a historical

education collection, a juvenile fiction collection, and a curriculum resources

collection for teacher candidates.

Research Questions

Reference desk interactions, directional statistics,

informal observations, and anecdotes from staff at the library’s Service Desk

all indicate that users experience difficulties navigating the library space

and locating resources. However, our current knowledge falls short of

understanding what actually happens when students leave the desk. Moreover, we

have very little meaningful knowledge of users’ personal experiences navigating

the library space. In seeking to fill these gaps, my research sought to answer

the following questions:

- How do users navigate the library?

- How do users locate places and items in the

library?

- Where are they successful?

- Where, specifically, do they encounter barriers?

- How do they perceive libraries?

Recruitment

I used a broad recruitment strategy directed to

students in the first year of their programs at OISE. I targeted new OISE

students because I sought participants with a range of library experiences but

also wanted to include students who were new to the OISE Library space. I sent

invitations to all of OISE’s incoming students via the Library’s Personal

Librarian Program emails (~1,000 students). Over 20 students responded, and I

was able to recruit 17 of those to complete the study. The 17 participants

represented a combination of frequent OISE Library users, students who had

never been to the OISE Library but had experiences in academic libraries, students

who described themselves as having rarely used any library (academic or

public), and several international students who considered the experience quite

different from library experiences in their home countries.

Method: Participant-driven photo-elicitation

At its basic level, photo-elicitation is a method that

employs photographs in interviews. I asked the research participants to

complete a short, independent photo survey followed by a one-on-one interview

to discuss the photos they made. For the photo survey activity, I asked

participants to walk through the OISE Library and complete tasks that they

might carry out on a trip to the library, including locating books (see Appendix

A - OISE Library Participant Photo Survey Tasks). I asked them to

photographically document their efforts and decisions along the way. I

reinforced that the intent of the tasks was not to test their ability to locate

library materials, but simply to get them moving through the library space.

Whether or not they located the items was not important.

Once participants had completed the photo survey

tasks, we met for an interview to discuss their photos and unpack their

experiences. The timing of interviews immediately following the photo survey

meant that participants could easily recall the intention of most of the

photos, and their feelings and experiences were still fresh in their minds. The

interviews themselves were very loosely structured, which allowed discussion to

emerge from the photos. After several introductory questions, most of the

interview questions were quite broad, and were driven by the participants’

photos: “Why did you take this one?” or “What’s happening here?” (see Appendix

B - OISE Library Interviewer’s Guide). This allowed the discussion to move

beyond the description of the photograph (“this is the stairwell”) and start

in-depth discussions about participants’ experiences with specific objects and

spaces.

My primary aim in using this style of structured PDPE

for the OISE Library study was to focus on navigation within the library.

Although I did provide specific tasks for participants to complete, I wanted to

ensure, as much as possible, that the data meaningfully reflected their

experiences in the space. In other words, I wanted to be able to focus on the

decisions they made, the photos they decided to take, and their explanations of what was important

in this exercise. This can be contrasted with methods where researchers are

present (e.g., Haberl & Wortman, 2012) or where

video cameras are used to document participants’ every move (e.g., Kinsley,

Schoonover, & Spitler, 2016). By handing them the

camera and allowing them to work through the tasks and space on their own, I

was asking participants to independently decide what was important, what they

wanted to photograph, to show and talk about.

University of

Victoria

Context

At the University of Victoria Libraries, we recently received some

funding to explore potential physical changes to all three campus libraries,

with the help of external consultants and architects. The interest in

implementing a research study using photo-narrative was to generate data on how

students use the library space as they are using it and what they think about

the space and design and how that impacts their experience. As mentioned,

photo-narrative is a type of photo-elicitation and differs only in the final

presentation of results where the photos and interview are used together to

create a narrative of telling of the experience. Also, a photo-narrative

approach lends itself to include an exhibition component. Although there are

three libraries on campus, the photo-narrative study focused on the Mearns

Centre for Learning/McPherson Library, the main library. The reason for this

limited scope was to make this research project more manageable.

Research Questions

For this particular study, the main research questions included:

- How are students using the library space?

- How do they shape or re-shape the spaces?

- What type of learning is going on in that

library space?

- What is missing from the space and design

that might impact their learning or general experience of the space?

These questions served to guide the project.

Recruitment

Aiming to generate a broad set of student experiences through the

photo-narrative study, all current undergraduate and graduate students were

eligible to participate in the study. After gaining Human Research Ethics

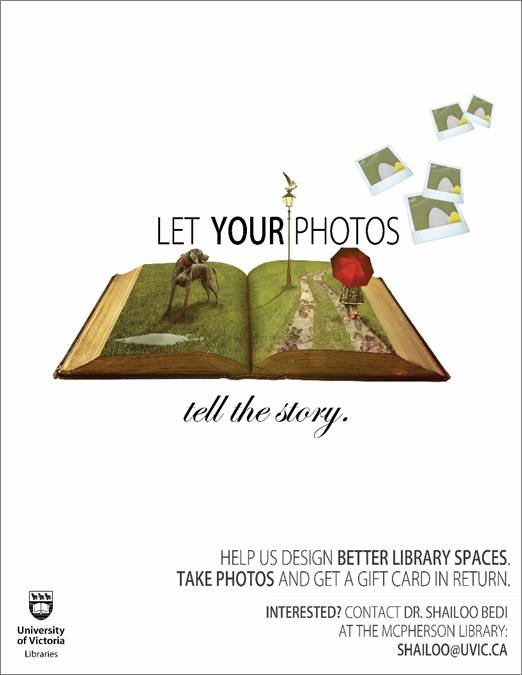

approval, I employed print and virtual promotional posters using the slogan

“Let your photos tell the story” (Appendix

C - University of Victoria Promotional Poster). In addition, I sent emails

to all department secretaries on campus asking them to put out a recruitment

email on their student listservs. My goal was to recruit between 10 to 15

students who use and experience the library space on a regularly basis. Student

research participants were not required to be professional photographers. Also,

no incentive was offered other than an enlarged image of a student photograph

that would be mounted as a thank you for their participation. Recruitment began

in September 2016, and 10 students took part in the study between September and

December 2016.

Method

As students

expressed interest to participate, I asked them to meet with me briefly to

review the research project, to sign a participant consent form, and to review

the ethics and privacy issues if taking photos that might include other

students. I also clarified with the students that they would keep the

intellectual property for their images and that they could choose to keep their

name attached to their photos. I provided the student research participants with

lanyard tags that identified them as student research participants and

encouraged them to spend some time collecting photos that represented their

experience and use of library space and design. Although most students opted to

use their smart phone cameras, some expressed interest in using a higher

resolution camera that they either owned or else borrowed from the University

of Victoria Libraries’ Music and Media unit. Once student participants had

completed collecting their photos, I asked them to meet for a semi-structured

interview where we would review their top 10-12 images that represented their

experiences (see Appendix D - University

of Victoria Interview Questions).

Another

component of this photo-narrative research project includes an opportunity for

participants to co-curate an exhibition in 2017 with me, featuring select

photos from each participant with an opportunity for viewers of the exhibit to

leave comments. The comments collected in the guestbook will be part of the

overall data collection for this photo-narrative study. Exhibiting as a method

of inquiry is occasionally used in combination with photo-narrative, not just

as a method of research

dissemination, but also to serve the purpose

of data collection. In this way, exhibition as a method of inquiry has the

potential to strengthen research participants’ connections to other viewers and

their environment (Gubrium & Holstein, 2012).

Gathering viewer input is focused on the shared experiences reflected in the

exhibited photos, and not on the quality of the image. Research participants

were asked to select the images they would like included in an exhibit and

could elect to remain anonymous in the display. The exhibition component of the

research was explained to all participants at the point of recruitment, and

consent to participate in the research clearly highlighted all components of

the research process.

Results

OISE Library

Participants’ photographs and the subsequent

interviews for the OISE Library Wayfinding Project yielded sophisticated

descriptions of their experiences navigating the library space. Between January

2015 and January 2016, a total of 17 participants made 533 photographs, ranging

from 4 photos from one participant to 75 from another. The follow-up interviews

yielded 536 minutes of interview recordings, with interviews ranging from 20-44

minutes.

Although the data analysis is not yet complete,

initial results point to some key areas where signage can be improved to help

make the journey through the library easier for users. In the first stage of

analysis I examined the recorded interviews and the accompanying photographs,

listening for mentions of things related to the photo tasks I provided. I did

not code the photographs separately from the interview transcripts. Rather,

they are stored together in NVivo and analyzed as part of the same dataset. To

address my research questions, I focused on gaining insights into the successes

and challenges participants faced in navigating the library, noting any

suggestions or recommendations they made. While the interviews reflected a wide

range of experiences and suggestions, three broad themes emerged from this

first phase that have proven valuable for recommendations for improvements.

They include: (1) the overall layout

of the library; (2) the consistency

of directional prompts, including naming conventions and the visual consistency

across collections, signage, call numbers labeling, and catalogue records; and

(3) the terminology used for

directional cues in the space. For the purposes of this article, I will briefly

discuss how photo-elicitation helped shed light on problems with the

consistency of directional prompts as well as the signage terminology at the

OISE Library.

Many participants described the process of locating

items as connecting “clues” (or directional prompts) they encountered over the

course of their journeys. They described observing clues in places like call

numbers, signage, the names of collections, or by the titles of the books, and

then making a guess about their next steps. Many participants remarked that

these clues did not always lead clearly to the next step in ways they expected.

One participant provided a brilliant example of where inconsistent naming

across signs, call numbers, and the catalogue record caused a temporary barrier

in her search for the second book on the list.

The first photograph in Figure 1, taken near the

entrance to the Children’s Literature Collection, prompted an in-depth

discussion about the inconsistent directional prompts Participant 6

encountered. For example, she pointed out that the book’s call number included

the letters “JUV FIC,” but the catalogue record indicated that the item was

located in the “Children’s Literature” collection, not the Juvenile Fiction

collection. In the section itself, there are signs that read “Juvenile Fiction”

and “The Margo Sandor Collection,” as well as labels that read “Children’s

Literature Collection (CLC)” but at the time there was no sign that clearly

indicated she had arrived in the Children’s Literature Collection area.

Ultimately, she said, “I just wasn’t sure what to trust” (Participant 6).

Figure 1

Participant 6’s photo of the Children’s Literature

Collection in the OISE Library, and the same photo as annotated by the

researcher after the interview.

In several other interviews, participants pointed to

terminology on key library signage and made comments that challenge what we

often take for granted when describing library spaces and collections. For example,

Figure 2 sparked a frank discussion with one student about the term “stacks”:

So, I saw that stacks was on the second floor, so I

went up and then I got lost and I wasn’t sure where I was anymore. And to be

honest [pointing to above photo], I don’t know what stacks means…. And then I

felt silly, I didn’t want to ask cause I thought that was a stupid question

[Participant 7].

As library insiders, we know that there are gaps in

the trail of clues our users attempt to follow. The photo-elicitation data,

tied to specific places and particular items in the OISE Library, provided

detailed insights into a library outsider’s journey. Participants' photographs,

coupled with their thoughtful discussions about library environments, provide

an alternate view that can re-open our eyes to things like signs and even

common terms such as “stacks” that have become second nature to those of us who

work in libraries. As Weber (2008) notes, participants’ photographs can make us pay

attention in new ways. Viewing my own library space in new ways allowed me to

pinpoint specific problems, such as inconsistencies in signage, or problematic

library terms, and to make suggestions for improvements.

In addition to providing evidence to support

improvements to the OISE Library’s signage, my initial analysis has revealed

new and unexpected insights into aspects of users’ library experiences that

went beyond my research questions. As a result, I plan to review the data to

explore additional themes that emerged around student-library relationships.

The initial analysis has already revealed some of the complexities about how

students inhabit library spaces, including how they work together (or don’t) to

develop etiquettes to share space and resources, the connections and ownership they

feel with the particular locations and items in the library, how they work around library policies and processes to

accomplish what they need, as well as the things make them anxious, and the

things make them happy.

Figure 2

Participant 7’s photo showing a sign for the stacks at

the OISE Library.

Figure three shows a photo made by Participant 1 to capture their favourite study spot. The participant explained that the combination of natural light and electrical outlets made this place “prime real estate.” The photo also led to a long discussion about the use of library spaces for events, the importance of quiet study spaces, and the sense of ownership students feel for their favourite library places. I hope the second phase of analysis will reveal more examples like this and open the door to potential new research questions regarding the student culture in library spaces.

University of

Victoria Libraries

The research

project is not yet complete at the University of Victoria. Although the data

collection from the student research participants has been completed, along

with the accompanying interviews, and the interview data has been analyzed, the

exhibition of photos is still forthcoming, and scheduled for late Spring 2017.

Since the guestbook comments are considered part of the data collection for

this study, the results are therefore incomplete. However, I am able to share

some emerging trends and themes from the photo collection and interviews with

participants.

Of the 10

participants, 6 students are graduate students, 3 in master’s programs and 3 in

doctoral programs. The remaining 4 are undergraduate students. Also worthy of

note is that 6 of the 10 participants identified as international students. All

but 3 agreed in having their name identified with the images they had taken,

while the others will be identified with pseudonyms for the

exhibition of photos and in any publications that include samples of the photos

from the study. In total, I recorded 314 minutes of interview time from 10

participants. The collection of photos exceeded the 10 to 12 images I requested

from each participant. The photos were not coded separately from the interview.

Rather, the themes emerged as part of the discussion with the research

participant that included their photos. This is an important part of a visual research

method, in that themes are not generated from the perspective of the researcher

but are co-constructed with the participant and the researcher.

From reviewing

the photos and interview data with each participant, the preliminary themes

include furniture, technology, lighting, artwork, and group learning space.

Within these themes there was much discussion about how each aspect was working

within each category, and also how each could be improved to make the student

experience even better. Although there is much to share and highlight from the

results, I will limit the discussion to only two of the themes: furniture and

lighting.

Figure 3

Participant 1’s

photo showing their favourite study spot in the OISE

Library.

The photos that

students took of the furniture, and as demonstrated through their interview

discussion, highlighted a strong appreciation of the variety of furniture

available to them, including large comfy chairs or sofas, individual study

carrels, large desks in the Learning Commons workstations, big open table

spaces, and the ever popular person-shaped Bouloum

lounge chairs. Although this variety was much appreciated, several students

took images of how worn-out some of the furniture fabric has become, making

them less appealing. Several commented on their reluctance to sit in such

spaces, but they often had no choice because the library very busy and full.

One participant commented, “…most days you are lucky to even get a seat, so you

just take what you can get. Really many students are sitting on the floor

between stacks…” This comment also pointed to another aspect of the furniture

theme, which is that we simply do not have enough

furniture to meet student needs. This was conveyed through photos that also

highlighted students spread out on the floor with their laptops, books, coats,

and backpacks.

The theme around

the lighting also had many equally positive reflections, including areas in the

library where lighting could be improved. Several students took images of the

large windows facing west that are almost floor to ceiling and look out on the

grassy quads and water fountain (see Figure 4).

Students’

comments about such images were overflowing with praise about the abundance of

natural light. One international student commented,

…coming from

China and my experience with my undergraduate library, we had very few windows.

The lighting was almost always fluorescent tubes. I feel my day is lucky when I

have the opportunity to sit at one of the large windows to study and…enjoy the

view of such a beautiful campus.Yet there were also

many photos of areas in the library that are dark and ominous (see Figure 5).

Figure 4

Participant’s

photo of natural light at UVic McPherson Library.

Figure 5

Participant’s

photo of a dark corner of UVic McPherson Library.

One student

mentioned that as a graduate student they

have an assigned carrel in one of the darkest and most closed off spaces

in the library. I really appreciate the carrel but find I move to another

carrel next to a window if it is not being used. I don’t like feeling like [I]

am in a cave, especially when I have hours ahead of me working on a laptop and

reading and composing.

Meanwhile,

another graduate student added,

if I can get a carrel by the window, I find I stay longer to do my

work…On the days, I can only get a study space in the dark areas of the

library, I don’t find I am as productive and I have a tendency to leave before

I am done what I planned.

The study

suggests that the quality of the lighting in the library impacts how long a

student will stay in the library and how much work they might complete.

Discussion

Strengths

One of the

commonly reported strengths of methods such as photo-elicitation or

photo-narrative is that the power of data collection is shifted, in part, into

the hands of the research participant (Liebenberg, 2009; Pink, 2001; Rose,

2012; Schwartz, 1989). In the two studies presented here, participants’

photographs acted as the main prompts during the interview, and this, in turn,

allowed the research participants drive more of the conversation. In this

context, the research participant is placed in an active role in co-constructing

knowledge with the researcher. Harper (2002) describes the collaborative work

inspired by photo-elicitation well, noting “When two or more people discuss the

meaning of photographs they try to figure out something together” (Harper,

2002, p. 23). Furthermore, the opportunity to incorporate an exhibition aspect

with a visual research method (as in the University of Victoria study), allows

for more voices to be included in the data-gathering phase of the research (Gubrium & Holstein, 2012).

Another key

strength of photographic methods is their applicability to spatial research.

The methods used in the two studies presented here allowed researchers to

follow lines of questioning with participants that tied participants’

experiences directly to particular locations, objects, signs, furniture, etc.

We are interested in how students’ experiences are interwoven with particular

spaces and objects, and the photographs served as visual queues

that prompted space-specific discussions that would be lost in other research

methods. For example, the photograph in Figure 1 prompted a description of

various signs visible from a particular location in the library. Then, building

on the description of the space, the participant’s comments broadened into a

conversation about the difficulties that inconsistent cataloguing, signage, and

labeling systems cause for library users. This type of detailed spatial

reference could not be elicited through methods such as focus groups or

surveys.

Some of the key

benefits of visual images for library research are also very practical. For

instance, both researchers found that working with images facilitated the

interview process and established a level of comfort between the researcher and

the participant. This is in line with Collier’s (2001) comment that photographs

can be seen as an “ice-breaker,” a medium that creates a comfortable space for

discussion.

Learning and

Recommendations

As with any

research project, we identified things we would do differently next time as

researchers. One key challenge we both experienced using photographic methods

was with the large amount of data that was collected. At the University of

Victoria, despite the criteria to the research-participants to bring only their

top 10-12 photos to the interview with the researcher, students wanted to share

many more photos than that. At times, this became quite overwhelming in guiding

the students to be more analytical about their images and experience, since

many students are accustomed to taking copious amounts of photos with today’s

technology and image-rich culture, perpetrated by the Internet and social

media. For those considering a similar approach, it might make sense request a

budget to buy disposable cameras with a finite number of exposures that would

ensure the same number and quality of images among research participants.

At the OISE

Library, participants also created a lot of photos, 533 in total. Because of

the “journey” style process, participants were documenting as they completed

the photo tasks, so allowing them to make an unlimited number of images worked

well. These images also flowed easily at the interview stage and really shaped

the telling of participants’ stories. However, because of the number of

participants involved, data analysis was labour

intensive. For researchers planning to use a data collection method such as

PDPE, the number of participants is also an important consideration. As key

patterns and themes begin to emerge in the interview process, consider whether

more data is needed to address the questions at hand. For the OISE Library

study, 10 participants would likely have provided the insights needed to

address the research questions.

A significant

and unexpected outcome of this project relates to the contributions of

international students. When international students at the University of

Victoria were asked why they were interested in the study, many spoke about the

comfort they had in the image-based nature of this research project. For many

of the international students, English was an additional language, but with the

focus of the study on photographs they felt there was a common language between

them and the researcher, especially during the interview phase. Similarly, one

international student participant at the OISE library also pointed to the

potential of photographs for research with international students. Although the

participant expressed concern about her English not being very good, she also

explained that she was excited for the chance to engage in research in a way

that allowed her to articulate her ideas through reference to her photographs.

International

students comprise a diverse group of users that have traditionally been on the

periphery in terms of engagement with library research projects at many

institutions. The interviews with international students in our two studies

suggest that they feel a positive connection to photographic research methods

because the use of images created an inclusive method to facilitate

participation by a diverse community of users. This outcome, while unexpected,

is consistent with Julien, Given, & Opryshko’s

2013 article that draws on feminist theory and puts forward photographic

methods as a way to highlight the voices of marginalized communities. This

outcome also inspires the need for more careful thought around the theoretical

frames that are associated with visual research methods, including Freire’s

(1970) foundational work in critical education, which aimed to empower

disadvantaged or marginalized communities, as well as the work of visual

researchers such as Wang & Burris (1994), who drew on Freire’s work and

feminist theory to develop the photovoice method as a research tool for

bringing voices to marginalized groups. The theoretical underpinnings as well

as the potential benefits of photographic methods for international students

and other marginalized student populations are areas for further exploration.

Conclusions

Preliminary findings from the two studies presented

support trends in the LIS literature that point to the value of photographic

methods in library research. We feel that photographic methods have a strong

role to play in understanding how spaces and objects shape user experiences.

Additionally, we found that photographic methods are well suited for providing

unexpected insights and engaging participants in meaningful discussions about

libraries. Although as researchers we set the criteria and parameters of the

projects and developed the photographic tasks and interview questions, the fact

that our participants were moving through the spaces by themselves and deciding

what to photograph led to many moments of realization for us during the

interviews. Whether it was the discovery of a long forgotten (and misleading)

directional sign, a personal admission that not understanding library

terminology was embarrassing, or an in-depth discussion about a student’s favourite place in the library, these unexpected lines of

discussion provided fresh perspectives on the spaces we take for granted.

Given that many

libraries are focusing their efforts on becoming user-centered

learning environments, it is critically important for librarians to continue to

ask research questions that help solve the needs of our users in our physical

spaces and to promote better physical access. Expanding our research methods

allows us to reach our users in different ways, and to promote better

engagement with them, and ultimately gain additional, and perhaps even more

meaningful, data. The photo-elicitation data presented here has already proven

productive in generating answers to our research questions and supporting

practical improvements to the library. Additionally, participants’ willingness

to describe the intentions of their photographs and engage in in-depth

conversations about libraries led to many unexpected insights for us. In fact,

it is in these moments (our “aha” moments) when we learn something completely

new about how users experience our libraries, that we enjoy this research the

most.

Acknowledgments

This paper was originally presented at the 2016 Centre

for Evidence Based Library & Information Practice (C-EBLIP) Symposium at

the University of Saskatchewan. The authors would like to thank Virginia Wilson

for her amazing work at C-EBLIP and for connecting our two research projects.

References

Briden, J. (2007).

Photo surveys: Eliciting more than you knew to ask for. In S. Gibbons, & N.

F. Foster, (Eds.). Studying students: The Undergraduate Research Project at

the University of Rochester (pp.

40-47). Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Brown, M. B., & Lippincott, J. K. (2003). Learning spaces: More than

meets the eye. EDUCAUSEreview,

1, 14-16.

Collier, J. (2001). Approaches to analysis in visual anthropology. In T.

van Leeuwen and C. Jewitt

(Eds.) Handbook of Visual Analysis.

(pp. 35-60). London, UK: Sage.

Ferria, A., Gallagher,

B. T., Izenstark, A., Larsen, P., LeMeur,

K., McCarthy, C. A., Mongeau, D. (2017). What are

they doing anyway?: Library as place and student use of a university library. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 12(1), 18-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B83D0T

Foster, N. F., & Gibbons, S. (2007). Studying students: The undergraduate research project at the University

of Rochester. Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the

oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum Publishing.

Gubrium, J.F., &

Holstein, J.A. (2012). Narrative practice and the transformation of interview

subjectivity. In J. F. Gubrium, J.A. Holstein, A. B. Marvasti, & K.D. McKinney, 27-43. , (Eds.). The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The

Complexity of the Craft. 2nd

ed. (pp. 27-43). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Haberl, V., & Wortman, B. (2012). Getting

the picture: Interviews and photo elicitation at Edmonton Public Library. LIBRES:

Library and Information Science Research Electronic Journal, 22(2), 1-20.

http://www.libres-ejournal.info/

Halpern, R., Eaker, C., Jackson, J. & Bouquin, D. (2015). #DitchTheSurvey:

Expanding methodological diversity in LIS research. In the Library with the

Lead Pipe. Retrieved from http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/ditchthesurvey-expanding-methodological-diversity-in-lis-research/

Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation.

Visual Studies, 17(1), 13-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14725860220137345

Harris, C. (2007). Libraries with lattes: The new third place. Australasian Public Libraries and

Information Services, 20(4), 145-152.

Hartel, J., &

Thomson, L. (2011). Visual approaches and photography for the study of

immediate information space. Journal of

the Association for Information Science and Technology, 62(11), 2214-2224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.21618

Julien, H., Given, L. M., & Opryshko, A.

(2013). Photovoice: A promising method for studies of individuals’ information

practices. Library & Information Science Research, 35(4), 257–263.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2013.04.004

Kinsley, K. M., Schoonover, D., & Spitler,

J. (2016). GoPro as an ethnographic tool: A wayfinding study in an academic

library. Journal of Access Services, 13(1), 7-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2016.1154465

Liebenberg, L. (2009). The visual image as discussion point: Increasing

validity in boundary crossing research. Qualitative

Research, 9(4), 441-467. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468794109337877

Lin, Y-C., & Chiu, M-H. (2012). A study of college students’

preference of servicescape in academic libraries. Journal

of Educational Media & Library Sciences, 49(4), 630-636. http://joemls.dils.tku.edu.tw/index.php?lang=en

Montgomery, S. E., & Miller, J. (2011). The third place: The library

as collaborative and community space in a time of fiscal restraint. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 18(2-3), 228-238.

Neurohr, K. A., &

Bailey, L. E. (2016). Using photo-elicitation with Native American students to

explore perceptions of the physical library. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 11(2), 56-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.18438/B8D629

Newcomer, N. L., Lindahl, D., & Harriman,

S. A. (2016). Picture the music: Performing arts library planning with photo

elicitation. Music Reference Services Quarterly, 19(1), 18–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10588167.2015.1130575

Pink, S. (2001). Doing visual ethnography: Images, media and

representation in research. London: Sage.

Pollak, A. (2017).

Visual research in LIS: Complementary and alternative methods. Library and Information Science Research,

39(2), 98-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2017.04.002

Rose, G. (2012). Visual

methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials (3rd

ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Schwartz, D. (1989). Visual ethnography: Using photography in

qualitative research. Qualitative

Sociology, 12(2), 119-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00988995

Treadwell, J., Binder, A., & Tagge, N.

(2012). Seeing ourselves as others see us: Library spaces through student eyes.

In L. M. Duke, & A. D. Asher, (Eds.). College libraries and student

culture: What we now know (pp.

127-142). Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

Wang, C., & Burris, M.A. (1994). Empowerment through photo novella:

Portraits of participation. Health

Education Quarterly, 21(2), 171–186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/109019819402100204

Weber, S. (2008). Visual images in research. In J. G. Knowles & A.

L. Cole (Eds.). Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives,

methodologies, examples, and issues, (pp. 42-54). London: Sage Publications.

Appendix A

OISE Library Participant Photo Survey Tasks

Library A Photo Survey Participant

Instructions

INSTRUCTIONS: Please use the following tasks to guide your

visit to the library and take photos along the way. Please return with the iPad

to the OISE Library Service Desk when you have completed the tasks. Have fun!

Task 1: Locate the following item:

Antler, J., & Biklen, S.

K. (1990). Changing education: Women as radicals and conservators.

Albany: State University of New York Press.

(call number 305.420973 C4562)

Please take photos

along the way.

Consider things like:

- Signage

- Locations and layout

- Tools you use, actions you take

- Things that helped as well as problems/barriers

Task 2: Make your way to the following item:

Cleary, B., & Tiegreen,

A. (1981). Ramona Quimby, Age 8. New York:

Dell.

(call number JUV FIC C623Rq)

Please take photos

alone the way.

Consider things like:

- Signage

- Locations and layout

- Tools you use, actions you take

- Things that helped as well as problems/barriers

Task 3: Anywhere in

the library, take photographs of the following:

- One or more places in the library where you felt

lost

- Something that helped or assisted you

- Something you really like

- Something you really dislike

- Anything

else that you take note of (good or bad!)

Appendix B

OISE Library Interviewer’s Guide

Thank the student

again for participating in the study. Review

the purpose of the study and the participant’s own participation. Review the

participant’s consent options, withdrawal options, compensation options, ways

the data will be stored and used, and the reason for the project.

We are interested in

what students really do in the library, how they locate information, and what

types of useful guides and barriers might exist in the OISE Library. We’ll be talking about the

photographs you took last week and I’ll be recording this session.

A few questions to get

started:

- Prior to this project, how often had you used the

OISE Library?

- How would you describe your overall experience

navigating the OISE Library?

Following these

initial questions, the interview will be guided by going through the

participants’ photographs and associated tasks. Questions will be open-ended

and will seek to elicit descriptions related to understanding the actions of

participants and how they navigated the library space. For example:

This photograph looks

like it is associated with Task #1 from the photo survey list. Tell me about

what’s happening here… Why did you take this one? Where did you go next? What

did you do next?

Once all the

photographs have been examined, the PI will ask the following questions:

1.

What was your least favorite activity in the photo tasks? Why?

2.

What are the key things you would change to

improve the OISE Library experience?

3.

Next time you have to locate something in the

OISE Library, what would you do? Would you try anything different?

4.

Do you have any other suggestions, thoughts, or

questions?

Following completion

of the interview, the PI will thank the participant again, sign off on

completion of participation and provide the incentive funds. The PI will ask

whether/how the student would like to be contacted with follow-up about the

research project and whether they would be interested in continuing to

participate on providing input to the OISE Library on service improvements.

Appendix C

University of Victoria Promotional Poster

Appendix D

University of Victoria Interview Questions

Interview Questions

Research Project: Student Experience of Library Space Told

through Student Photo-narratives

This interview questions used with research

participants in a semi-structured interview to discuss their top 10 to 12

photos.

- Tell me about the photographs you have selected.

- Why have you selected these images?

- If you were to describe your images, what would you say about

them?

- How do these images resonate with your experiences of library

space?

- What struck you as particularly interesting or concerning about

the space?

- Did you learn something about your use of space you were not

aware of before this project? If so, what?

- From this experience, what are the top 3 things that library

could do to improve your experience of library space?

For the photography exhibit, what impression

about student use of library space would you like viewers to walk away with? And

why?