Research Article

What Happened After the 2012 Shift in Canadian

Copyright Law? An Updated Survey on How Copyright is Managed across Canadian

Universities

Rumi Graham

University Copyright Advisor

& Graduate Studies Librarian

University of Lethbridge

Library

Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada

Email: grahry@uleth.ca

Christina Winter

Copyright Officer

University of Regina Library

Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada

Email: christina.winter@uregina.ca

Received: 3 Jan. 2017 Accepted:

9 June 2017

2017 Graham and Winter. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Graham and Winter. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – The purpose of this study is to understand the practices and

approaches followed by Canadian universities in copyright education,

permissions clearance, and policy development in light of major changes to

Canadian copyright law that occurred in mid-2012. The study also seeks to

identify aspects of copyright management perceived by the universities to be

challenging.

Methods – In

2015, an invitation to complete an online survey on institutional copyright

practices was sent to the senior administrator at member libraries of Canada’s

four regional academic library consortia. The invitation requested completion

of the survey by the person best suited to respond on behalf of the

institution. Study methods were largely adapted from those used in a 2008

survey conducted by another researcher who targeted members of same library

consortia.

Results – While

the university library maintained its leadership role in copyright matters

across the institution, the majority of responding institutions had delegated

responsibility for copyright to a position or office explicitly labeled

copyright. In contrast, respondents to the 2008 survey most often held the

position of senior library administrator. Blanket licensing was an accepted

approach to managing copyright across Canadian universities in 2008, but by

2015 it had become a live issue, with roughly half of the respondents

indicating their institutions had terminated or were planning to terminate

their blanket license.

Conclusion – In just seven years we have witnessed a significant increase in

specialized attention paid to copyright on Canadian university campuses and in

the breadth of resources dedicated to helping the university community

understand, comply with, and exercise various provisions under Canadian

copyright law, which include rights for creators and users.

Introduction

The

instrumental role of copyright in Canada is to properly balance two competing

ends: protection of creators’ private rights to stimulate the creation of new

works, and wide dissemination of creative works to advance the public interest

in learning, innovation and cultural enrichment (Théberge v. Galerie d’Art,

2002, para. 30). Observing that “Canadian universities have not generally been

proactive in managing copyright and knowledge transfer” (p. 7) while the

complexity and contested nature of copyright’s balancing act intensify

steadily, Horava (2010) conducted a survey in the

summer of 2008 to explore how academic libraries and their parent institutions

view and manage communication about copyright.

At

the time of the 2008 survey, a blanket reprographic licensing regime existed

across Canada’s publicly funded primary and secondary (K to 12) schools,

colleges and institutes, and universities. The regime was formed over the

decade following the 1988 Copyright Act amendments that expanded the scope of

managing copyright collectively. One product of that round of statutory reforms

was CanCopy, a literary works collective now called

Access Copyright (AC), which has operated since 1989 throughout Canada except

in the province of Quebec (Friedland, 2007). Quebec’s

literary works collective, Copibec, was formally

established in 1998 (Soderstrom, 1998). Educational

institutions entered into blanket licensing primarily due to uncertainty

regarding whether classroom copying can qualify as fair dealing under the

Copyright Act (Graham, 2016).

Within

two years of Horava’s (2010) survey, discord was

palpable in the post-secondary copyright realm as an initial attempt to renew

another AC model blanket license agreement was unsuccessful. Shortly after

negotiations broke down, AC filed its first proposed tariff for post-secondary

educational institutions in March 2010, which, to date, has yet to be certified

(Copyright Board of Canada, 2010). The decision of some institutions not to

renew their AC license after the August 2010 expiry date marked the beginning

of a movement away from blanket licensing. Unrest was heightened by legislative

and judicial proceedings in the last quarter of 2011. Parliament embarked on

yet another attempt to modernize the Copyright Act that had better prospects of

success due to the majority government, and in an unprecedented two-day period

the Supreme Court of Canada heard a total of five copyright cases.

Two

pivotal events brought matters to a head in mid-2012. First, Parliament passed

An Act to Amend the Copyright Act (2012), which, among other things, expanded

the “user’s right” (CCH v. LSUC,

2004, para. 12, 48) of fair dealing to include education. Second, the Supreme

Court delivered its rulings in the five copyright cases (Alberta (Education) v. AC, 2012; ESA v. SOCAN, 2012; Re:Sound v. MPTAC,

2012; Rogers v. SOCAN, 2012; SOCAN v. Bell, 2012), which have since

sparked much legal and academic debate, an example being the collection of

essays entitled The Copyright Pentalogy:

How the Supreme Court of Canada Shook the Foundations of Canadian Copyright Law

(Geist, 2013a). Of critical importance to educators was the pentalogy case in

which the Court determined that teachers’ copying of short excerpts for

classroom use can qualify as fair dealing if, on a properly conducted analysis,

the dealings, on the whole, can be shown to be fair (Alberta (Education) v. AC, 2012).

The

subsequent emergence of a “fair dealing consensus” among educators (Geist,

2012) prompted many institutions to revise their copyright management approach,

taking into account the fair dealing ruling in Alberta (Education) v. AC (2012) and expanded statutory fair

dealing provisions (e.g., Noel & Snel, 2012;

Universities Canada, 2012). K to 12

schools outside of Quebec withdrew from blanket licensing in 2013 (e.g., Geist,

2013b), but in 2015 the extent to which universities had followed suit was

unclear. Factors contributing to a climate of uncertainty were the Copyright

Board’s post-secondary tariff proceedings, copyright lawsuits against two

blanket licensing opt-out universities (Access Copyright, 2013; Copibec, 2014), and, for institutions covered by a

five-year AC blanket license that became available in Spring 2012, the question

of whether or not to renew before the license expired in December 2015.

Since

the authors are responsible for copyright at our respective institutions, we

were interested in discovering how the recent major developments in copyright

law have affected copyright practices and approaches at other universities. We

learned that Horava had no plans to update his 2008

survey but received his encouragement to pursue a similar investigation

ourselves (personal communication, September 14, 2014). We therefore undertook

this study to explore the current state of copyright education, permissions management,

and copyright policy development at Canadian universities as well as what has

changed in these areas over the past five to seven years.

Literature Review

The

two main issues examined by the 2008 survey were the locus of responsibility for

copyright within respondents’ library and university, and challenges

encountered in educating university community members about copyright (Horava, 2010). Almost 60% of respondents to the 2008 survey

held the senior administrative role in their library while only four

respondents (6%) were copyright officers. Responsibility for copyright within

respondents’ institutions was roughly equally often located in the library, in

central administration, or shared by the library and another campus unit (each

representing about 30% of all responses). The survey responses thus revealed a

wide variety of institutional approaches to managing copyright and educating

the university community.

Among

the challenges identified by the 2008 survey respondents was a lack of

institutional coordination in copyright management and education (Horava, 2010, p. 10). Others were concerned about overlaps

between copyright and various kinds of licensing, including blanket licensing

and licensing of electronic resources. Horava’s (2010)

recommendation that library websites should “explain the university licence with copyright collectives” (p. 28) confirms

blanket licensing was then the status quo. Doubts about its necessity were

nonetheless voiced by respondents in comments such as the following: “I suspect

we are often licensing and paying for access that is available to us under fair

dealing esp. since the CCH case. I think an argument could be made that we no

longer need Part A of the Access Copyright licence” (Horava, 2010, p. 21).

In

2008, few empirical studies were available on academic library perceptions and

practices regarding copyright communication (Horava,

2010). Although they remain relatively scarce, a more recent investigation in

this area is a multiple-case study by Albitz (2013)

on how research universities manage copyright education. Using Mintzberg’s organizational model as a theoretical lens, Albitz (2013) conducted semi-structured interviews with 11

copyright officers at member institutions of the U.S.-based Consortia on

Institutional Cooperation. Among the topics explored were the locus of

copyright education and copyright officers’ responsibilities, credentials, and

perceptions of authority. Albitz found that it is

most important for the copyright officer at research universities to hold a

Juris Doctorate in intellectual property law, and that it is helpful but

somewhat less important for the position to be located within the library

rather than central administration.

Applying

a critical theory perspective, Di Valentino (2013) assessed understandings of

copyright law as reflected in fair dealing policies adopted by Canadian

universities outside of Quebec. This inquiry was guided by an interest in

“reducing schools’ reliance on private contracts and in promoting awareness of

fair dealing rights, and in reversing the trend of basing copyright compliance

on the avoidance of liability, which prevents users from taking full advantage

of their rights” (Di Valentino, 2013, pp. 14-15). The study’s examination of

institutional copyright websites showed that while most universities had a fair

dealing policy or set of guidelines, the presented copyright information was at

times explained inconsistently, was inaccurate or unnecessarily restrictive, or

was indicative of a strong tendency toward risk aversion.

In

another investigation, Di Valentino (2015) extended Horava’s

(2010) study by “looking at the issue from the other side” (p. 5). Faculty at

Canadian universities outside of Quebec were surveyed on their understanding of

institutional copyright policies and services and their practices regarding

copyright compliance. Di Valentino’s (2015) findings established that faculty

were broadly aware of institutional copyright policies, but 40% of respondents

were unsure about whether copyright training was available. Faculty appeared to

be comfortable when using publicly accessible Internet content in class but

much less confident about the permissibility of making an electronic copy of

excerpts for course use.

Aims

The

aim of our 2015 survey was to discover what has changed in the copyright

practices and approaches of Canadian universities since Horava’s

2008 survey. Three areas of central interest were:

1.

copyright

education, including instructional methods and topics;

2.

copyright

policy and the status of blanket licensing; and

3.

permissions

management for copied course materials distributed via coursepacks

(collections of readings and other course materials selected by instructors),

print and electronic reserve (e-reserve), and the institutional learning

management system (LMS).

Within

these three areas we sought to identify the locus of responsibility; to find

out what changes, if any, had occurred within the past five years; and to

identify institutional copyright challenges.

Methods

The

methods and survey questions used in our study are chiefly adapted from those

employed by Horava (2010). Both researchers obtained

approval for the study’s protocols from the research ethics review office at

our home institutions. Because our investigation, like that of Horava’s, was national in scope, the survey and

communications to invited respondents were translated into French. Our

web-based survey was created using an instance of LimeSurvey

hosted by the University of Lethbridge Library. Two parallel versions of the

survey were created, affording the option for participants to respond in either

English or French. Survey responses received in French were translated into

English.

Because

the spotlight on copyright in Canada had begun to intensify in 2010, questions

about changes in practices asked respondents to reflect on the past five years.

Unlike Horava’s study, our survey was completely

anonymous to encourage wide participation. Another point of divergence was our

decision to focus on institutional approaches and practices rather than those

belonging to the university library, since institutions may choose to situate

responsibilities for copyright outside of the library. As well, given that Di

Valentino (2013) had recently looked at information about copyright and fair

dealing on Canadian university websites, we excluded questions about copyright

webpages.

We

also chose to look at two areas not covered by the 2008 survey—permissions

clearance and blanket licensing—as they are pertinent in this time of flux

within national and international educational copying contexts (e.g., Cambridge v. Becker (2012); Cambridge v. Becker (2016); Cambridge v. Patton (2014)). A draft

version of the survey was pre-tested by two library colleagues at Canadian

colleges. Their feedback is reflected in the final version comprising 18 open-

and closed-ended questions (see the Appendix), which is similar in length to Horava’s (2010) 2008 survey containing 19 questions.

Applying

Horava’s approach, an invitation to complete our

survey was sent to the university librarian or library director at the member

institutions of Canada’s four regional academic library consortia: Council of

Atlantic University Libraries (CAUL), Bureau de Coopération

Interuniversitaire (BCI), Ontario Council of

University Libraries (OCUL), and Council of Prairie and Pacific University

Libraries (COPPUL). Recipients were asked to have the survey completed by the

institutional staff best suited to do so. The 79 universities invited to

participate in our survey is a slightly larger total than the 75 institutions

invited to complete Horava’s 2008 survey.

Our

2015 survey opened for one month in early March 2015, with a reminder issued

about one week prior to the closing date. Since we desired a response rate

comparable to that of the 2008 survey but the initial response rate was low,

with the approval of our research ethics offices we re-opened the survey for

another month in mid-October 2015. A reminder was sent about three weeks later.

Results

Respondents

Our

2015 survey produced 48 responses: 22 were received in March-April 2015 and a

further 26 followed in October-November 2015. The overall 61% response rate

fell short of the 84% response rate obtained by Horava

(2010, p. 9), but represents a sizable improvement over the initial response

rate of 28%. All geographic regions of Canada were represented in responses to

the 2015 survey: 38% were from Eastern Canada (CAUL) and Quebec (BCI), 25% were

from Ontario (OCUL), and 37% were from Western Canada (COPPUL). Response rates

by consortium ranged from a low of 47% to a high of 78% (see Table 1). Horava (2010) did

not report the consortial distribution of 2008 survey

responses.

Table 1

Survey Respondents by Consortium, 2015

|

Member Libraries

|

2015 Respondents

|

Response Rate

|

|

CAUL

|

16

|

9

|

56%

|

|

BCI

|

19

|

9

|

47%

|

|

OCUL

|

21

|

12

|

57%

|

|

COPPUL

|

23

|

18

|

78%

|

|

Totals/Average

|

79

|

48

|

61%

|

Figure 1

Survey respondents by institutional size (FTE), 2015 and 2008.

Figure 2

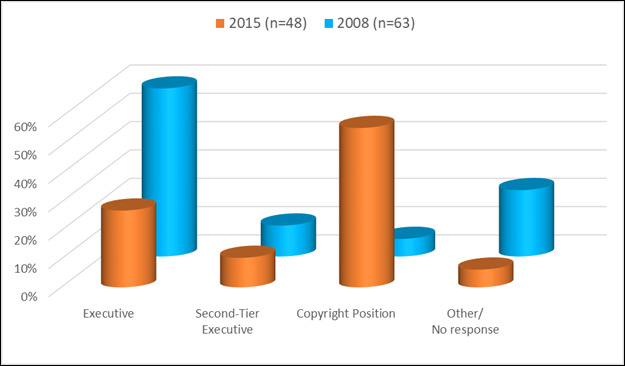

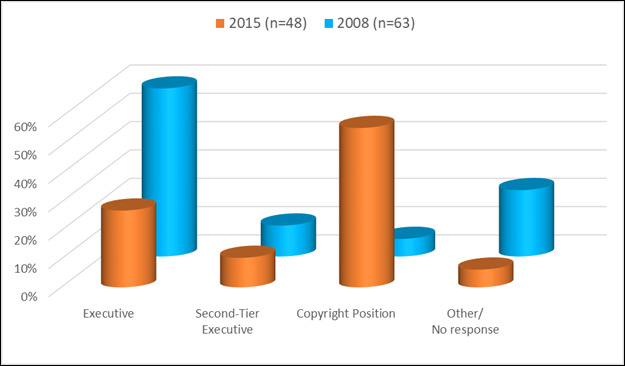

Survey respondents by position title, 2015 and 2008.

The 2008 and 2015 surveys both asked about the size of

respondents’ institutions, based on full-time equivalent (FTE) students. As

seen in Figure 1, respondents’ institutions in 2008 (Horava,

2010, p. 11) and 2015 were proportionally similarly sized. For both surveys,

almost half of the respondents were from small institutions, with the other

half roughly equally split between medium and large institutions.

One

difference between the results of the two surveys is a remarkable growth in the

number of institutional positions specifically dedicated to copyright in 2015,

as indicated in Figure 2. In 2008, 59% of survey respondents held executive

positions (university librarian or library director) and only 6% held

copyright-specific positions (Horava, 2010, p. 11).

By 2015, 56% of respondents held copyright positions and only 27% held the

senior library executive position. In both 2008 and 2015, about 10% of

respondents held second-tier executive (associate university librarian)

positions.

Locus of

Responsibility

The 2015 survey questions on the position, department

or office responsible for copyright education, policy and permissions were

open-ended and did not ask respondents to specify the administrative locus

associated with each answer. Responses that referenced a copyright office or

position within the library were coded under “Library.” When two or more

positions or campus units were mentioned, the response was coded under

“[first-named unit] shared” (e.g., “Library shared”). Our survey results thus

do not allow us to make a clear distinction between copyright offices managed

by the library and copyright offices managed by other campus units, as only

some responses happened to name the locus of administrative oversight

associated with the identified responsible unit or position.

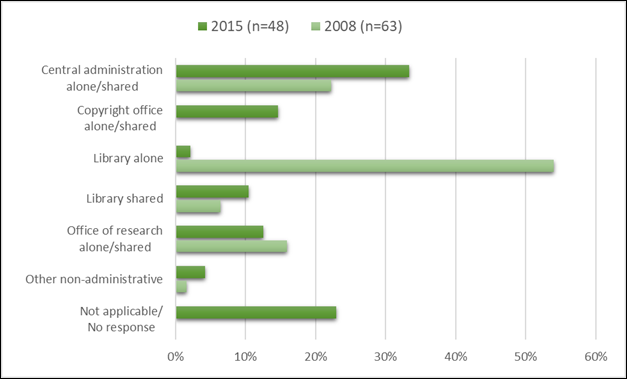

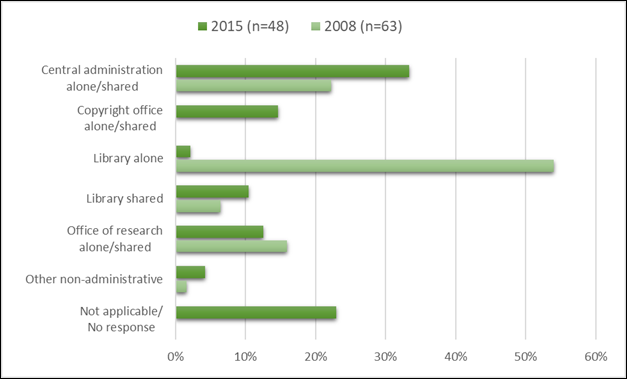

Figure 3

Responsibility for copyright education, 2015 and 2008.

Responsibility for Copyright Education

In 2008 (Horava, 2010, p. 13) and 2015, most respondents (between

50% and 60%) said the locus of institutional responsibility for copyright

education resided with the university library acting either alone or with other

campus units.

Figure 3 indicates the campus unit next most often identified as being

responsible for copyright education in 2015 (27%) was the copyright office

acting alone or in a shared capacity, but in 2008 it was central administration

(29%). Thus, between 2008 and 2015 some movement is discernable, as

responsibility for copyright education formerly located in central

administration appears to have been transferred to the copyright office.

Responsibility

for Policy or Services for Owners of Copyrighted Materials

Both surveys examined the locus of responsibility

for matters pertaining to copyright owned by employees and students in works

created in the course of employment or academic studies. The questions probing

this issue were somewhat different, however. The 2008 survey asked whether a

campus unit other than the library was responsible for managing copyright from

a rights-holder’s perspective and if they answered “yes,” respondents were

asked to specify the unit (Horava, 2010, p. 35). The

2015 survey instead asked which campus unit was responsible for developing policies

on ownership of copyrighted materials. Despite differences in how they are

framed, the gist of both questions is the identity of the campus unit

responsible for helping authors and other creators understand and protect their

copyright interests.

Figure 4

Responsibility for policy (2015) and service (2008) provisions for copyright

owners.

Figure 5

Responsibility for policy on use of copyrighted works, 2015.

As shown in Figure 4, more than 50% of responses to

the 2008 survey indicated the library was responsible for helping owners

protect their copyright interests, and a further 40% said this responsibility

was held by central administration or the office of research (Horava, 2010, p. 15). The 2015 responses to the somewhat

different question about responsibility for copyright ownership policy indicate

the responsible unit was most often central administration alone or in a joint

capacity. But in 2015 when responsibility for policy on copyright owners’

rights was situated outside of central administration, the responsible units

were roughly equally often the copyright office, the office of research, or the

library, each acting alone or with other campus units.

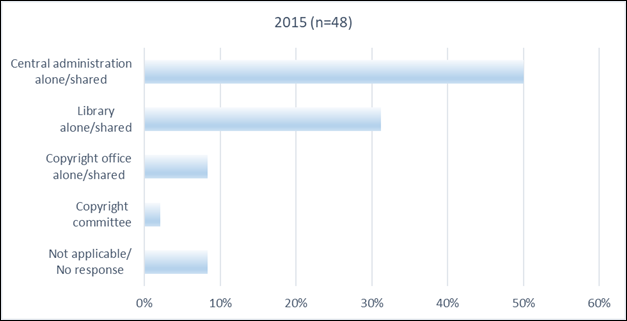

Responsibility

for Policy on Uses of Copyrighted Materials

The locus of responsibility

for institutional policy relating to copyright compliance and use of

copyrighted materials was a question explored only in the 2015 survey. Figure 5

indicates that by far the campus unit most often holding this responsibility, alone

or in a joint capacity, was the library, followed at a distance by the

copyright office, which together account for two-thirds of responses. The

extent to which central administration and copyright committees led

user-focused policy development is relatively modest as they were identified as

the responsible unit by under 20% and under 10% of

respondents, respectively.

Responsibility for Permissions Clearance

Permissions clearance is the process of first

assessing whether a work is protected by copyright and whether permission to

use the work is needed, and then, when necessary, obtaining copyright owner

consent. The Supreme Court decisions in CCH

v. LSUC, 2004 and Alberta (Education)

v. AC, 2012 as well as the 2012 Copyright Act amendment that added

education as a fair dealing purpose together provide educational institutions

with a much-enriched understanding of the applicability of statutory user’s

rights to educational uses of copyrighted works. Institutional responsibility

for clearing permissions for course-related use of copyrighted materials was a

second issue explored only in the 2015 survey.

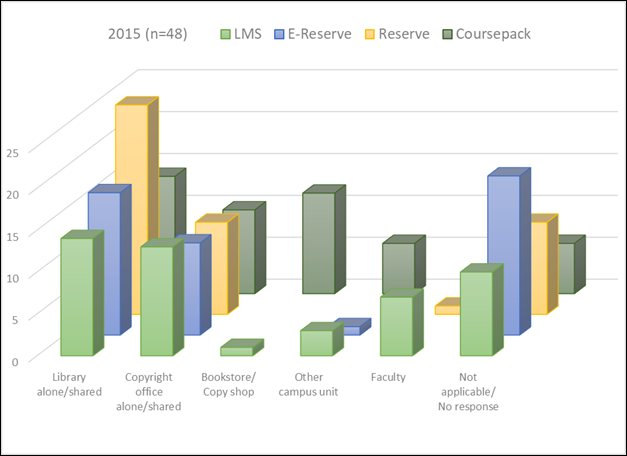

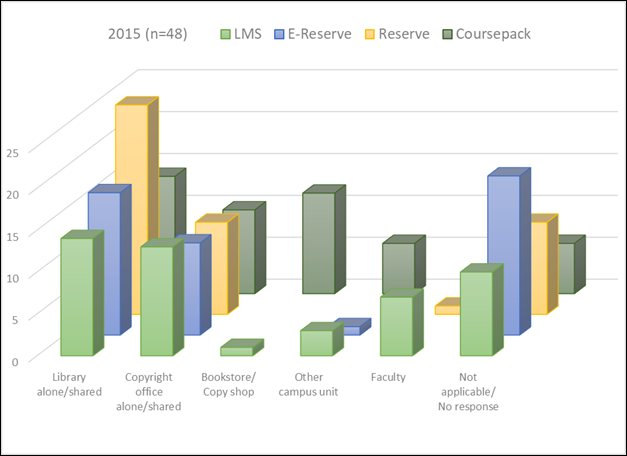

Figure 6

Responsibility for permissions clearance, 2015.

Figure 6 shows that the library, acting alone or in a

shared capacity, was across the board most often identified as being

responsible for permissions clearance for materials distributed via the LMS,

e-reserve, print reserve, and coursepacks. The unit

next most often responsible for permissions clearance was the copyright office,

alone or shared, for all distribution modes except coursepacks

where the bookstore or commercial copy shop was in second place. LMS

permissions clearance was the responsibility of the teaching faculty at seven

institutions.

Responsibility

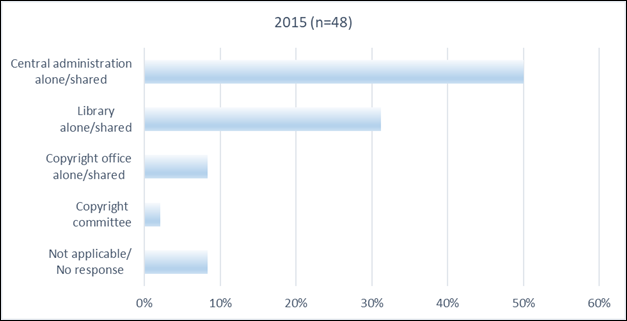

for Blanket Licensing

A

third aspect of copyright responsibility considered only in the 2015 survey

pertains to decisions on institutional blanket licensing. As presented in

Figure 7, 50% of respondents said this responsibility was the purview of

central administration alone or in a shared capacity, but more than 30%

indicated issues relating to blanket licensing were decided by the library

acting alone or jointly with other campus offices. Thus, most institutions

considered blanket licensing to be a matter for either central administration

or the university library. About 10% indicated blanket licensing matters to be

the responsibility of the copyright office acting alone or with other offices,

or a copyright committee.

Figure 7

Responsibility for blanket licensing decisions, 2015.

Table 2

Methods Used to Educate Users of Copyrighted Works, 2015 and 2008

|

User

Education Method

|

Frequency of

Response

2015 (n=45)

|

Frequency of

Response

2008 (n=62)

|

|

individual

assistance

|

33.3%

|

77.4%

|

|

information

literacy

|

68.9%

|

66.1%

|

|

faculty

liaison/outreach

|

28.9%

|

64.5%

|

|

reference

service

|

---

|

62.9%

|

|

webpage

|

86.7%

|

62.9%

|

|

printed

information

|

17.8%

|

50.0%

|

|

online

tutorial

|

4.4%

|

19.3%

|

|

other

|

24.4%

|

11.2%

|

|

none

|

2.2%

|

4.8%

|

Copyright Education

Education for

Users of Copyrighted Works

Although

the 2008 and 2015 surveys both asked about methods used to educate users of

copyrighted materials, the question was posed in different ways. The 2008

survey presented a list of education methods and asked respondents to check off

all that applied, whereas the 2015 survey question was open-ended, resulting in

an inability to make exact comparisons between the two sets of responses.

Nevertheless, in most cases the categories of education methods arising in 2015

responses were mappable to those used in the 2008

survey (Horava, 2010, p. 22), presented in Table 2.

In 2008, users most often received education via individual assistance, but in

2015 responses the most frequently mentioned education method was webpages.

Information literacy was the second most frequently used education method in

2008 and 2015. In 2015, no respondents mentioned reference service as an

education method, and unlike 2008 respondents, very few said print materials

were used. “Other” user education methods noted in 2015 were e-mail, guidelines

or policy statements, and mailings or newsletters. Very few 2015

respondents—about 2%—said no copyright user education was offered.

Education for Creators of Copyrighted Works

An open-ended question in the 2015 survey asked about

methods used to educate creators about their copyrights. For ease of comparing user education methods

to those used in creator education, Table 3 summarizes the latter under the

same categories used in Table 2, which were borrowed from Horava

(2010). Responses to the 2015 survey indicate the most frequently identified

method of providing copyright information to both creators and users of

copyrighted works was webpages. “Other” means of providing copyright education

to creators mentioned by 2015 survey respondents were collective agreements,

e-mail, guidelines or policy statements, mailings or newsletters, and

university committees. More than 13% of responses indicated copyright education

for creators was not offered.

Copyright Education Topics

The topics addressed in education directed at users

and creators of copyrighted works are another aspect of copyright education

considered only in the 2015 survey. Table 4 reveals the two most frequently

identified copyright user education topics to be copyright infringement

exceptions (users’ rights), with strong emphasis placed on the fair dealing

provisions of the Canadian Copyright Act. As evidenced in Table 5, the three

most frequently mentioned topics of education directed at creators of

copyrighted works were creators’ or owners’ copyrights, negotiating publisher

contracts or addenda, and open access. Four topics are common to Tables 4 and

5, indicating their relevance to both users and creators of copyrighted works:

fair dealing, copyright basics (key provisions of the Copyright Act), copyright

permissions or licensing, and open access.

Table 3

Methods Used to Educate Creators of Copyrighted Works, 2015

|

Education

Methods for Creators

|

Frequency

of Response (n=45)

|

|

individual

assistance

|

24.4%

|

|

information

literacy

|

37.8%

|

|

faculty

liaison/outreach

|

22.2%

|

|

webpage

|

64.4%

|

|

printed

Information

|

6.7%

|

|

other

|

22.2%

|

|

none

|

13.3%

|

Table 4

Topics Addressed in Education for Users of Copyrighted Works, 2015

|

Education

Topics

|

Frequency

of Response (n=45)

|

|

fair

dealing

|

66.7%

|

|

exceptions

to infringement

|

28.9%

|

|

copyright

basics

|

22.2%

|

|

copyright

permissions or licensing

|

22.2%

|

|

copyright

compliance and ethical use of protected works

|

20.0%

|

|

open

access

|

20.0%

|

|

course-related

copying

|

17.8%

|

|

images

|

13.3%

|

|

LMS

use

|

13.3%

|

|

digital

or multimedia works

|

11.1%

|

|

how

to obtain help with copyright issues

|

11.1%

|

|

coursepacks

|

6.7%

|

|

motion

pictures and videos

|

6.7%

|

|

library-licensed

resources

|

6.7%

|

|

reserve

or e-reserve

|

6.7%

|

|

materials

accessed or streamed from the Internet

|

6.7%

|

|

attribution

or source citation

|

4.4%

|

|

public

domain

|

4.4%

|

|

blanket

licensing

|

2.2%

|

|

not

applicable or in development

|

4.4%

|

Changes in Copyright Education

Most respondents (77%) said their institution’s

approach to copyright education has changed appreciably over the past five

years. Table 6 summarizes several broad themes identified in respondents’ brief

explanations of what has changed.

Copyright

Policy

Policy Scope and Content

The 2008 survey asked whether university copyright

policy guided, or was guided by, the library’s provision of copyright

information and vice versa (Horava, 2010, p. 35).

Rather than looking at the extent to which university copyright policy and

library-provided copyright information were influenced by the other, the 2015

survey sought to determine the prevalence of institutional copyright guidelines

or policies as well as the issues they address.

Of the 48 respondents to the 2015 survey, 81%

confirmed the existence of institutional guidelines or policy pertaining to

copyright. Just under 70% of respondents who shared the topics of institutional

policy mentioned fair dealing, and 41% said policy covered copyright basics.

The specificity of the subject matter of institutional copyright policies

appears to vary widely as respondents identified topics ranging from the narrow

issue of defining the meaning of “short excerpt” to the broad matter of the

public domain, as evidenced in Table 7.

Table 5

Topics Addressed in Education for Creators of Copyrighted Works, 2015

|

Education

Topics

|

Frequency

of Response (n=43)

|

|

creators'

or owners' copyrights

|

53.5%

|

|

negotiating

publisher contracts or addenda

|

37.2%

|

|

open

access

|

37.2%

|

|

copyright

basics

|

18.6%

|

|

Creative

Commons licensing

|

11.6%

|

|

fair

dealing

|

11.6%

|

|

copyright

permissions or licensing

|

11.6%

|

|

publishing

protocols, models, avenues

|

9.3%

|

|

predatory

publishing

|

9.3%

|

|

self-archiving

|

7.0%

|

|

granting

agency policies

|

4.7%

|

|

author-side

publication charges (APCs)

|

2.3%

|

|

theses

and dissertations

|

2.3%

|

|

moral

rights

|

2.3%

|

|

faculty

collective agreement

|

2.3%

|

|

waiving

or sharing copyrights

|

2.3%

|

|

not

applicable or in development

|

14.0%

|

Table 6

Aspects of Copyright Education That Have Changed, 2015

|

Broad

Themes

|

Frequency

of Response (n=40)

|

|

education

programs launched or intensified

|

65.0%

|

|

new

copying environment due to terminated blanket license

|

35.0%

|

|

education

programs moved to copyright office

|

30.0%

|

|

new

or revised help pages and guidelines

|

30.0%

|

|

new

case law and statutory amendments

|

20.0%

|

|

new

administrative structures or processes

|

10.0%

|

Table 7

Topics Addressed by Institutional Copyright Guidelines or Policy, 2015 (n=39)

|

Policy

Topics

|

Frequency

of Response

|

|

fair

dealing

|

69.2%

|

|

copyright

basics

|

41.0%

|

|

course-related

copying

|

15.4%

|

|

public

performances

|

5.1%

|

|

staff

policy regarding copyright compliance

|

5.1%

|

|

copyright

office

|

2.6%

|

|

definition

of short excerpt

|

2.6%

|

|

exhibition

rights

|

2.6%

|

|

use

of images

|

2.6%

|

|

moral

rights

|

2.6%

|

|

copyright

permissions

|

2.6%

|

|

ownership

of works produced by university employees

|

2.6%

|

|

public

domain

|

2.6%

|

Table 8

Copyright Policy Year of Establishment and Last Revision, 2015

|

Time

Period

|

Policy

Established

Frequency

of Response (n=48)

|

Policy

Last Revised

Frequency

of Response (n=48)

|

|

before

1997

|

8.3%

|

--

|

|

between

1997 and 2010

|

8.3%

|

4.2%

|

|

2011

and after

|

54.2%

|

39.6%

|

|

not

applicable/no response

|

29.2%

|

56.3%

|

Policy Establishment and Revision

The 2015 survey asked respondents to identify the date

on which their institution’s copyright policy was established as well as the

date on which the policy was last revised. Table 8 indicates more than half of

the institutions (54.2%) had established copyright policies in 2011 or later,

which likely accounts for most of the slightly greater proportion of

institutions (56.3%) that did not provide a policy revision date.

About 63% of survey respondents were unable to

identify the main areas of change in the most recent copyright policy revisions

or did not respond to this question. Areas of policy revisions mentioned by

four to six respondents were Copyright Act amendments, fair dealing, outcomes

of copyright court cases, and educational exceptions to infringement. Other

policy revision areas identified by one or two respondents were library

licenses, blanket licensing, digital copies, a shift to individualresponsibility

for copyright compliance, and copyright and teaching.

Institutions in 2015 most often used the university’s

copyright website to communicate copyright policy to their communities, as

shown in Table 9. The next most frequently mentioned means of communicating

institutional policy on copyright were e-mail and meetings.

Participation in Blanket Licensing

Although publicly funded Canadian post-secondary

institutions were blanket licensees from the 1990s to at least 2010, by 2015

some had announced their withdrawal from the blanket licensing regime (Katz,

2013). About 44% of respondents to the 2015 survey said their institution had

terminated their blanket license and 4% did not answer the question about

blanket licensing, leaving just over half of respondents, 52%, whose

institutions remained blanket licensees. But an even greater proportion, 62%,

said their institution had opted out of blanket licensing in the past. Furthermore, five respondents (10%) at

institutions holding an AC blanket license said plans to exit the license were

underway.

Table 9

Methods of Communicating Copyright Policy to University Community Members, 2015

|

Communication

Method

|

Frequency

of Response (n=48)

|

|

copyright

website

|

60.4%

|

|

e-mail

|

29.2%

|

|

meetings

|

29.2%

|

|

university

news

|

16.7%

|

|

workshops

|

14.6%

|

|

personal

communication by staff specialists

|

8.3%

|

|

administrative

memos

|

6.3%

|

|

newsletters

|

6.3%

|

|

posters

|

4.2%

|

|

click-through

agreement on LMS

|

2.1%

|

|

checklists

|

2.1%

|

|

not

applicable/no response

|

22.9%

|

Table 10

Consideration of Library Licenses as Permission Sources for Course Readings,

2015 (n=48)

|

In-House

Coursepacks

|

Copy

Shop Coursepacks

|

LMS

Readings

|

Print

Reserve Readings

|

E-Reserve

Readings

|

|

yes

|

66.7%

|

12.5%

|

52.1%

|

70.8%

|

58.3%

|

|

no

|

8.3%

|

18.8%

|

12.5%

|

10.4%

|

6.3%

|

|

uncertain

|

10.4%

|

18.8%

|

31.3%

|

10.4%

|

4.2%

|

|

not

applicable

|

10.4%

|

45.8%

|

4.2%

|

4.2%

|

27.1%

|

|

no

response

|

4.2%

|

4.2%

|

0.0%

|

4.2%

|

4.2%

|

|

100.0%

|

100.0%

|

100.0%

|

100.0%

|

100.0%

|

Table 11

Format of Copyright Permission Tools, 2015

|

Tool

Format

|

Frequency

of Response (n=23)

|

|

permissions

clearance services and education

|

47.8%

|

|

copyright

management software

|

30.4%

|

|

guide

for copyright and permission decisions

|

21.7%

|

|

copyright

clearance form for instructors

|

13.0%

|

|

look-up

tool for permitted uses of licensed content

|

8.7%

|

|

model

permission clearance letters

|

8.7%

|

|

tool

offered by a copyright collective

|

8.7%

|

|

website

information

|

8.7%

|

Table 12

Institutional Copyright Challenges, 2015

|

Challenge Area

|

Challenge Themes

|

Frequency of Response

|

|

Education

|

communicating copyright information effectively

and comprehensively

|

76.7%

|

|

(n=43)

|

ensuring copyright/licensing compliance

|

30.2%

|

|

overcoming obstacles to compliant practices

|

18.6%

|

|

addressing staffing and staff expertise

requirements

|

9.3%

|

|

dealing with legal and statutory interpretation

uncertainties

|

7.0%

|

|

evaluating a possible move away from blanket

licensing

|

4.7%

|

|

helping faculty and students understand their

copyrights and publication choices

|

4.7%

|

|

|

|

|

Policy

|

fostering policy understanding and compliance

|

57.9%

|

|

(n=38)

|

applying policies appropriately

|

21.1%

|

|

establishing or updating institutional policy

|

15.8%

|

|

monitoring copyright and licensing compliance

|

7.9%

|

|

achieving appropriate staffing for policy-related

education and services

|

7.9%

|

|

addressing specific policy-related issues

|

7.9%

|

|

|

|

|

Permissions

|

managing administrative challenges of permissions

clearance service

|

42.9%

|

|

(n=35)

|

helping users understand why permissions are

important and how to assess them

|

34.3%

|

|

acquiring permissions for specific kinds of works

|

31.4%

|

|

securing administrative support for permissions

staffing, systems or tools

|

22.9%

|

|

acquiring permissions generally

|

5.7%

|

Copyright

Permissions

Applicability of Library Licenses

The first of two 2015 survey questions on copyright

permissions asked if the applicability of library licenses is assessed when

permissions are cleared for course readings distributed via coursepacks,

the LMS, print reserve, or e-reserve. As indicated in Table 10, between 52% and

71% of respondents said that library licensing is taken into account when

permissions are cleared for readings distributed in all modes except coursepacks produced by commercial copy shops. The greatest

degree of uncertainty about whether library licenses are considered in the

permissions clearance process pertained to readings distributed via the LMS.

Permission Tools

In response to the second question about permissions,

52% of respondents said one or more tools had been developed to help university

community members clear copyright permissions, 44% indicated no tools had been

developed, and 4% said the question was inapplicable. Table 11 summarizes the

formats of permission tools developed by universities, as described by respondents.

Educational,

Policy, and Permissions Challenges

In each of the three key areas probed by the 2015

survey, respondents were asked to identify the most significant challenges

faced by their institutions. Single dominant concerns surfaced within the areas

of copyright education and copyright policy. For copyright education, the

institutional challenge mentioned in 77% of responses was effective and

comprehensive communication of copyright information. For copyright policy,

fostering understanding of and compliance with institutional policy was the

challenge noted in 58% of responses. No single concern was dominant in the area

of permissions challenges, but managing administrative aspects of permissions

service and helping users understand and perform permissions clearance were

identified in 43% and 34% of responses, respectively. Table 12 outlines themes

that arose within the challenges identified in all three areas.

The

following are examples of comments submitted by respondents in the three areas

of copyright challenges faced by universities. Some of the mentioned challenges

pertained to more than one challenge area:

Education:

·

“Staffing

for an intensive educational effort. Entrenched practices of some faculty and

staff members.”

·

“Meet

with lecturers, make existing class notes compliant, ensure that teaching staff

comply with institutional policy on fair use.”

·

“Reaching

everyone. Multi-campus environment.”

·

“Creating

buy-in from faculties and departments, who may simply view copyright clearance

and related steps as hindrances or obstacles, rather than as a fundamental

component of post-secondary education.”

Policy:

·

“Connecting

the institutional policy to specific compliance practices/procedures.”

·

“Re-writing

the Fair Dealing Guidelines to make them more user-friendly, less daunting,

shorter while still being useful.”

·

“Ensuring

compliance with FD Policy and identifying individuals who will need assistance

transitioning from working under the AC License to the FD Policy.”

·

“We

do not have a policy or guideline on converting physical AV media to formats

that allow our institution to stream video content to distance students or

web-based courses.”

Permissions:

·

“Permission

for French documents (especially European, costly and long delays).”

·

“Our

permissions process is quite labour intensive. No

database currently in place to support full workflow process.”

·

“Materials

in copyright but orphaned. Dealing with copyright with regards to music,

lyrics, recordings etc.”

·

“Reapplying

for permissions – keeping track of continuing use and when permissions expire.

Ensuring instructors and staff are aware of which permissions need

reapplication. Getting publishers to reply to requests in a timely manner.”

Discussion

Responsibility for Copyright

Results

of this study evidence several areas of marked change in the copyright

practices and approaches of Canadian universities since 2008. While the library

continued to play a prominent role in copyright education from 2008 to 2015, a

shift in the locus of responsibility from central administration to the

copyright office is notable. Our survey did not reveal reasons for this change,

but a possible inference is that it was precipitated by foundational shifts in

the copyright landscape that heightened concern about copyright issues across

Canadian universities and a perceived need for specialized copyright expertise.

A

reverse shift took place in the area of copyright ownership policy or advocacy.

While the library was most often responsible for promoting and protecting

rights-holders’ interests in 2008, the largest proportion of 2015

respondents—about one third—said responsibility for owner-focused policy was

most frequently held, alone or jointly, by central administration. At the same

time, the proportion of 2015 respondents who said this responsibility belonged

to the library or copyright office, alone or with other units—one quarter—was

not far behind.

The

2015 survey results show the university library most often played the lead role

in permissions clearance for course materials made available to students via

four common distribution modes. The unit next most frequently responsible for

permissions clearance was once again the copyright office, acting alone or with

others, for all distribution modes except coursepacks.

Overall,

the 2008 and 2015 survey results indicate the library is the primary locus for

most matters related to copyright. This attestation of the library’s continued

copyright leadership role within Canadian universities notwithstanding, in

several cases the copyright office served as the institutional lead unit in

copyright matters. Moreover, the position held by the majority of survey

respondents in 2015 specialized in copyright, whereas in 2008 most respondents

held the position of university librarian or library director.

Educational Approaches and Topics

As

more than three quarters of 2015 survey respondents said their institution’s

approach to copyright education had changed, methods used to educate university

staff and students about copyright clearly evolved between 2008 and 2015.

Compared to 2008, copyright user education in 2015 far less often involved

individual assistance, faculty outreach, reference service, and print

materials, but had become more heavily dependent on copyright webpages. On the

other hand, reliance on information literacy remained strong, as about

two-thirds of respondents in both 2008 and 2015 said their institution used

this approach in copyright user education.

Copyright

education for creators was not explicitly investigated in the 2008 survey, but

in 2015, the most frequently used method of educating creators was making

copyright information available via webpages, with information literacy in

distant second place. It may be the case that more attention is paid to

educating copyright users than copyright creators: while the proportion of

respondents who provided no information about their institution’s user

education methods was very small, it was six times greater for creator

education.

Only

the 2015 survey explored the topics addressed in copyright education. Fair

dealing was clearly a central concern, as it was identified as a focus of

copyright user education by more than two-thirds of respondents. The next most

frequently addressed topic in user-focused education, exceptions to

infringement in general, was identified by roughly one-third of respondents.

Fair dealing was also addressed in copyright education for creators, but not as

frequently as creators’ copyrights, negotiating publishing agreements, and open

access.

The

vast majority of 2015 survey participants’ institutions provided copyright

education that was directed most often at copyright users and was somewhat less

frequently tailored to copyright creators. Tables 4 and 5 indicate fair

dealing, copyright basics, copyright permissions or licensing, and open access

were addressed in education directed at both groups. This suggests copyright

educators recognize the importance of ensuring that their institutional

communities understand the fundamental interdependence of provisions for users’

rights and creators’ rights in the Copyright Act, given that everyone is both a

user and creator of copyrighted material.

Fair

dealing and open access promote the public interest in lawful, wide public use

of protected intellectual works. At the same, they also assist creators who

wish to build upon prior ideas and knowledge or disseminate their works

broadly. Similarly, rights granted to copyright owners under the Act, including

the right to authorize uses of their works, provide a means for creators to

control certain uses of their works. When users wish to use protected works in

ways not otherwise covered, knowing how to seek permissions properly will help

users protect themselves against unintentional infringement.

The

broad array of topics addressed in copyright education and the fact that

respondents said the greatest change in this area was new or intensified

educational programs evidence a serious commitment by Canadian universities to

enhance awareness and understanding throughout their communities of users’ and

creators’ rights under the Copyright Act.

Policy Prevalence and Focal Points

We

assume 100% of institutions represented in the 2008 survey results held a

blanket copying license, whereas only 52% of 2015 survey respondents said their

university was a blanket licensee. This finding aligns with those of Di

Valentino (2013) who reported slightly over half of the institutions in her

sample (41 universities outside of Quebec) had an AC blanket license. The

premise that almost all educational copying requires permission was questioned

by a few of Horava’s 2008 respondents, but by 2015,

more than half of the universities responding to our survey had parted ways

with blanket licensing or had definite plans to exit their license in the near

future. Blanket licensing as a policy approach to copyright compliance is thus

a live issue currently trending toward reliance on alternative approaches.

New

developments have also unfolded in other aspects of copyright policy. Well

above three quarters of the 2015 survey respondents said their university had

instituted a copyright policy or guidelines. It is notable that more than half

of responding institutions initiated copyright policy for the first time in

2011 or later. Likely related to this finding is the fact that several

respondents said their institution adopted the 2012 revision of the fair

dealing policy that was developed and recommended by the Association of

Universities and Colleges Canada (now Universities Canada). As well, having a

copyright policy in place was possibly a particular concern for institutions

who were, or were moving toward, operating without a blanket license. Of the

topics covered in copyright policy, the one identified in more than two-thirds

of responses was fair dealing. The next most common focal point of

policy—copyright basics—was mentioned in less than half of responses.

Taken

together, these developments suggest institutional approaches to copyright

policy in 2015 had evolved substantially since 2008. The proportion of

universities opting out of blanket licensing was nearing 50% and adoption of

institutional copyright policy was prevalent, with a primary focus on the

user’s right of fair dealing.

Permissions Clearance Practices

Responses

to the 2015 survey indicate that library licenses for full-text resources are

assessed by most universities during permissions clearance for all modes of

distributing course readings except commercially produced coursepacks.

All the same, roughly one-third of survey respondents did not know whether

clearing permissions for materials distributed via the LMS took into account

the potential applicability of library licenses. Reasons for this relatively

high level of uncertainty level are unclear, but one respondent’s comment

raises an issue that may be applicable in settings where instructors are

responsible for LMS permissions clearance: “I have put ‘Uncertain’ . . .

because we do provide the information and tool so that teaching faculty can

check if use is covered by our licenses but we do not have data as to what

level it is used.”

More

than half of the responding institutions said they had developed tools to help

institutional community members clear copyright permissions. The form of those

tools was most often permissions clearance services or education, or copyright

management software. These findings point to considerable investment of various

kinds of resources to enhance permissions assessment and management at Canadian

universities.

Challenges

The

challenges in copyright education identified by 2008 and 2015 survey

respondents, on the whole, touch on similar themes, the most common in 2015

being effective and comprehensive communication of copyright information to all

university community constituencies. This challenge is likely to remain an

important and large undertaking because copyright encompasses inherently

complex concepts and requirements that are difficult to reduce to simple,

memorable ideas while remaining true to how the copyright system actually

works.

In

2015, the most frequently identified challenges in the policy and permissions

arenas were fostering copyright policy understanding and compliance, and

managing administrative aspects of permissions, respectively. The former

essentially covers much the same ground as the most frequently identified

challenge in the area of copyright education:

communicating copyright information effectively and comprehensively.

Respondents’ comments indicate administrative aspects of permissions challenges

involve issues such as significant delays in securing permissions in a timely

fashion and dealing with large volumes of uses needing permissions clearance

without adequate staffing levels.

The

challenge themes arising from the 2015 survey collectively suggest universities

appreciate the importance of ensuring that their communities and operations are

properly guided by the provisions of current copyright law and licensing

agreements. Interestingly, the lack of institutional coordination of copyright

matters regarded by many 2008 survey respondents as a major organizational

challenge (Horava, 2010, p. 27) did not arise as a

strongly articulated concern in 2015.

Limitations

The

overall goal of the 2015 survey was to gain a well-rounded picture of current

institutional copyright practices and aspects that may have changed since 2008.

A limitation of our study is that its response rate, while strong, was markedly

lower than the rate achieved in the 2008 survey. Reasons for the lower response

rate are unclear, although uncertainty regarding the outcomes of legal and

tariff proceedings are likely contributing factors.

Another

limitation is that our survey necessarily yields only a snapshot of copyright

practices and approaches at a time when many Canadian universities held a

blanket AC license with a December 2015 expiry date. Since our study was

conducted just prior to this deadline, in several cases the current status of

blanket licensing and other aspects of institutional copyright policy and

practices may differ from the responses we received to licensing questions in

2015.

A

further limitation is the omission of survey questions that might have shed

more light on the administrative relationship between the copyright office and

the library as well as the specific nature and scope of positions holding

responsibility for various aspects of copyright. We decided against their

inclusion to contain the length of the survey in order to encourage wide

participation.

Future research

Our

study uncovered considerable growth in the number of copyright-specific

positions since 2008. Because our survey did not ask whether these were new

hires or the result of reallocation of existing personnel to a dedicated

copyright position, however, this issue is worthy of investigation in a future

study. We note that Horava (2010) also identified the

role of copyright officers as an area for further research. Some ground work

has already been laid by Patterson (2016) in an examination of the role of Canadian

copyright specialists in universities. Additional areas warranting further

inquiry include the copyright practices and approaches and role of copyright

specialists in other types of educational institutions, such as K to 12

schools, community colleges, and polytechnical

institutes.

Conclusion

Framed

as an update to Horava’s 2008 survey, our study

explored the extent to which Canadian universities have responded to several

major developments in Canadian copyright law by adjusting their copyright practices

and approaches. Horava (2010) noted new workflows and

positions were developed over the 2000s to support a new priority on acquiring

licensed digital content that occurred with little attention paid to copyright

or the volume of information transfer. In contrast, our study results indicate

a much-elevated level of copyright awareness is prevalent at Canadian

universities, as evidenced by the topics covered in current copyright education

and copyright policy and by the variety of tools and resources available to

help users clear copyright permissions for teaching and research purposes.

A

variety of approaches still exist, but shared practices may now be more common,

as several respondents noted their institutional copyright policy was modeled

on the 2012 revised Universities Canada fair dealing policy and Di Valentino

(2013) found this same policy had been “adopted in some way” (p. 17) by many

universities in her study. We suggest institutions sharing similar copyright

policies are also likely to share broadly aligned copyright practices. A

specific change in approach is reflected in the far greater prevalence of

copyright-specific positions and offices in 2015. University libraries

nevertheless maintain a lead role in the areas of copyright education,

copyright use-focused policy, and permissions clearance, with copyright offices

often having the distinction of being next most likely to hold the lead role.

Universities

appear to be paying greater and more nuanced attention to copyright policy and

copyright education from users’ and creators’ viewpoints. Given that fair

dealing was by far the most frequently identified focus of institutional

copyright policy and copyright education for users, it is apparent that

provisions for user’s rights in the Copyright Act have achieved a heightened

prominence and importance on Canadian university campuses.

Despite

substantive challenges that remain in the copyright realm, over the past

several years Canadian universities have evidently augmented the attention and

resources dedicated to ensuring their communities, on the one hand, understand

and comply with Canadian copyright law, and on the other hand, are aware of and

fully exercise the Copyright Act’s provisions for user’s rights such as fair

dealing.

Acknowledgements

This

study was partially funded by a 2015 research grant from the Canadian Library

Association. The authors thank Tony Horava for

permission to adapt the survey instrument used in his 2008 study.

References

Access

Copyright. (2013). Canada's writers and publishers take a stand against

damaging interpretations of fair dealing by the education sector [Press

release]. Retrieved from http://accesscopyright.ca/media/35670/2013-04-08_ac_statement.pdf

An Act to

Amend the Copyright Act (2012, S.C., ch. 20).

Retrieved from

http://www.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?Language=E&Mode=1&DocId=5697419

Alberta

(Education) v. Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), 2012 SCC

37 Supreme Court of Canada, (2012). Retrieved from https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/9997/index.do

Albitz, R. S.

(2013). Copyright information management and the university library: Staffing,

organizational placement and authority. Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 39(5), 429-435. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2013.04.002

Cambridge

University Press v. Becker, 863 F. Supp. 2d 1190 (N.D. Ga., 2012). Retrieved

from http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=univ_lib_copyrightlawsuit

Cambridge

University Press v. Becker, 863 F.Supp.2d 1190 (N.D. Ga., 2016). Retrieved from

http://policynotes.arl.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/DKT-No.-510-Order-dated-2016_03_31.pdf

Cambridge

University Press v. Patton, 769 F.3d 1232 (11th Cir. 2014). Retrieved from http://media.ca11.uscourts.gov/opinions/pub/files/201214676.pdf

CCH

Canadian Ltd. v. Law Society of Upper Canada, 2004 SCC 13 Supreme Court of

Canada, (2004).

Retrieved from https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/2125/index.do

Copibec. (2014). $4

million class action lawsuit against Université Laval

for copyright infringement [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.copibec.qc.ca/Portals/0/Fichiers_PDF_anglais/NEWS%20RELEASE-Copibec%20Novembre%2010%202014.pdf

Copyright

Board of Canada. (2010). Statement of

proposed royalties to be collected by Access Copyright for the reprographic

reproduction, in Canada, of works in its repertoire: Post-secondary educational

institutions (2011-2013). Ottawa,

ON: Copyright Board of Canada. Retrieved from http://www.cb-cda.gc.ca/tariffs-tarifs/proposed-proposes/2010/2009-06-11-1.pdf.

Di Valentino,

L. (2013, May 9). Review of Canadian university fair dealing policies. FIMS Working Papers. Retrieved from http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/fimswp/2

Di Valentino,

L. (2015). Awareness and perception of copyright among teaching faculty at

Canadian universities. Partnership: The

Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 10(2),

1-16. doi:10.21083/partnership.v10i2.3556

Entertainment

Software Association v. Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of

Canada, 2012 SCC 34 Supreme Court of Canada, (2012). Retrieved from https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/9994/index.do

Friedland, M. L.

(2007). Report to Access Copyright on

distribution of royalties. Toronto: Access Copyright. Retrieved from http://www.accesscopyright.ca/media/8359/access_copyright_report_--_february_15_2007.pdf

Geist, M.

(2012). Fair dealing consensus emerges within Canadian educational community.

[Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.michaelgeist.ca/content/view/6698/125/

Geist, M.

(2013a). The copyright pentalogy: How the

Supreme Court of Canada shook the foundations of Canadian copyright law.

Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

Retrieved from http://www.press.uottawa.ca/sites/default/files/9780776620848.pdf

Geist, M. (2013b).

Ontario government emphasizes user rights in its copyright policy for

education. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.michaelgeist.ca/2013/07/ontario-govt-copyright-policy/

Graham, R.

(2016). An evidence-informed picture of course-related copying. College & Research Libraries, 77(3),

335-358. doi:10.5860/crl.77.3.335

Horava, T. (2010).

Copyright communication in Canadian academic libraries: A national survey. Canadian Journal of Information and Library

Science, 34(1), 1-38. doi:10.1353/ils.0.0002

Katz, A.

(2013). Fair dealing’s halls of fame and shame, 2013 holiday edition. [Blog

post]. Retrieved from http://arielkatz.org/archives/3064

Noel, W.,

& Snel, J. (2012). Copyright matters! Some key questions & answers (3rd ed.).

[Toronto, ON]: Council of Ministers of Education. Retrieved from http://cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/291/Copyright_Matters.pdf

Patterson, E.

(2016). The university copyright

specialist: A cross-Canada selfie. Paper presented at the ABC Copyright

Conference 2016, Halifax, NS. Retrieved

from http://abccopyright2016.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/ABC-2016.pdf

Re:Sound v. Motion

Picture Theatre Associations of Canada, 2012 SCC 38 Supreme Court of Canada,

(2012). Retrieved from https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/9999/index.do

Rogers

Communications Inc. v. Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of

Canada, 2012 SCC 35 Supreme Court of Canada, (2012). Retrieved from https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/9995/index.do

Society of

Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada v. Bell Canada, 2012 SCC 36

Supreme Court of Canada, (2012). Retrieved from http://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/9996/index.do

Soderstrom, M. (1998).

New licencing agency in Quebec. Quill & Quire, 64(3), 13.

Théberge v. Galerie d’Art du Petit Champlain inc., 2002 SCC 34 Supreme Court of Canada, (2002).

Retrieved from https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/1973/index.do

Universities

Canada. (2012, October 9). Fair dealing policy for universities. Retrieved from http://www.univcan.ca/media-room/media-releases/fair-dealing-policy-for-universities/

![]() 2017 Graham and Winter. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Graham and Winter. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.