Introduction

One of the key future

trends in higher education identified in both the “New Media Consortium (NMC) Horizon Report” (Johnson, Adams Becker, Estrada, & Freeman, 2014)

and the “Top Trends in Academic Libraries” (Association of College and Research

Libraries [ACRL] Research Planning and Review Committee, 2014) is the integration of online, hybrid,

and collaborative learning. Like many academic institutions, Griffith

University is moving to online modes of course delivery. For learning advisers

and information literacy librarians to address this shift, it is necessary to

engage with the e-learning environment. A core first year Bachelor of Business

course moving into the online environment presented the opportunity for

collaboration between an information literacy librarian, a learning adviser, an

academic, and an educational designer in the creation of an online resource for

the teaching of research and writing skills in support of student assessment.

Literature supports the

concept that embedding academic and information literacy skills into first year

university courses enables students to proceed more confidently with

researching and writing their assignments, and thus contributes to student

success in their course. The creation of online embedded resources represented

a new direction for library teaching and learning at Griffith University.

Therefore, it was necessary to assess the impact of the resources to clarify

the library’s contribution to student success and academic library value.

Drawing on measures and

methods identified in Information and Documentation: Methods and Procedures for

Assessing the Impact of Libraries, ISO16439” (International

Organisation for Standardisation [ISO], 2014), evidence was collected

and combined from a variety of sources to assess the impact of the online

resource. The evidence shows that this resource contributed to student success,

and that staff and student satisfaction with the resource contributed to

increased student confidence with academic and information literacy in respect

to their essay assessment task. An integral part of this success was due to the

collaboration between information literacy librarians and other stakeholders in

providing academic and information literacy support to the first year business

student experience and engagement.

Background

Griffith University offers

a mixed mode method of delivery which consists of face to face and online

offerings in courses and importantly, requires equity of access to services for

both on-campus and online students. The University consists of five campuses

over South East Queensland, with a student body of over 43,000. The Griffith

Business School, with a student population of over 11,000, delivers courses at

all five campuses as well as online. Historically, embedded information

literacy skills and academic skills have been taught face to face in lecture

time; however, due to the increasing amount of course content to be covered in

lecture times, the opportunity to contribute has been severely reduced in the

Griffith Business School. As more students move into the online method of

course delivery, face to face delivery also represents a lack of equity in

delivery for these students. Embedding online literacy resources offered an

opportunity to redress this issue for a compulsory first year Bachelor of

Business course, which had over 1,000 students enrolled. The online resource

“Research and Writing for Business Students” (the Module) was created in collaboration with the course

academic, the educational designer responsible for getting the course online,

and Business Team Library and Learning staff, consisting of an information

literacy librarian and a learning adviser.

Eight topics covering

researching, writing, and referencing were included in the Module to support

these students in their essay assignment task. The eight topics created

consisted of:

- Navigating the library website

- Unpacking the question

- Scholarly and peer reviewed journal articles

- Searching the library catalogue

- Writing the plan

- Searching Google Scholar

- Writing the essay

- Referencing

These topics covered the

key academic and information literacy skills needed to scaffold the completion

of the essay assignment task. The Module was positioned in the course

assessment folder, below the essay assignment task, in the learning

management system, Blackboard, in semester 2, 2014 and semester 1, 2015. It was

utilised in several tutorial and workshop sessions by course tutors to explain

key literacy skills needed to complete the essay assignment task, and so was

highly embedded into the teaching of the course.

Initial discussions about

the creation of the resource highlighted the need for seamlessly embedding it

in the course and for it not to appear as an add-on. To do this it was necessary

to use the same interface and design established for the rest of the course and

for the resource to be purposely built for the specific essay assignment task.

Each topic of the Module included a short YouTube video with additional

information and links to further resources, and focussed on the specific essay

assignment task. The topics were personalized as much as possible in order to

engage with students in the online environment, as suggested in the NMC Horizon Report (Johnson et al., 2014). For example, “searching the library

catalogue” used keywords relevant to the essay assignment task, and “writing

the essay” utilised exemplars provided by the academic.

The Module was designed in

collaboration with the educational designer to complement the overall course

interface, and the content was created in collaboration with the library

business team learning adviser and librarian and the course

academic. Importantly, it was strategically envisaged that the template

for the Module and some topics could also be repurposed in other courses.

Literature review

Collaboration

Embedding information

literacy and academic writing instruction into course curricula is not new.

Literature supports that a collaborative approach to the embedding of

information literacy instruction in course curricula has positive outcomes for

students (Creaser et al., 2014; Menchaca, 2014;

Nelson, 2014; Pan, Ferrer-Vinent, & Bruehl, 2014). A

three-pronged collaboration model between an academic, a learning adviser, and

an information literacy librarian has been suggested to overcome the often

unrelated way that information literacy and academic skills have been presented

in the past to university students (Einfalt

& Turley, 2009, 2013; Kokkinn & Mahar, 2011; Taib & Holden, 2013).

Tinto (2005) suggests that any support given to students should be

related to a specific course and a specific task in order to help students

succeed in that course and actively involve them in learning. Theis, Wallis,

Turner, and Wishart (2014) agree that the

development of students’ academic literacies is enhanced through the use of

curriculum embedded resources rather than add-on generic offerings from the

library.

Any support strategy must

be contextualised and connected to the environment

in which student learning takes place (Nelson,

2014). The “NMC Horizon Report” (Johnson

et al., 2014) identifies the rise of online pedagogy at higher education

institutions. The e-learning environment can provide a student-centred approach

where students can proceed at their own pace and use different media types that

suit their style of learning (Lu & Chiou, 2010). For information and

academic literacy resources to be useful in an online environment,

collaboration in creation should be widened from the three-pronged approach to

include an educational designer in order to enhance the environment in which

the resources are to be placed (Gunn, Hearne,

& Sibthorpe, 2011). As such, a four-pronged collaboration model

between librarian, learning adviser, educational designer, and course academic

was used in the development of the Module.

Evaluation

“The Value of Academic

Libraries: A Comprehensive Research Review and Report” (Oakleaf, 2010)

summarizes the importance for academic libraries to demonstrate their value,

particularly in light of budgetary restraint and competing stakeholder

interests. This importance is also

emphasised in other studies (Bausman, Ward, & Pell, 2014; Brown &

Malenfant, 2012; Creaser & Spezi, 2012, 2014; Gibson & Dixon, 2011;

Tenopir, 2011). Rather than just reporting on library achievements, Kranich,

Lotts, and Springs (2014) explore the notion of academic libraries turning

outward so that library impact is measured in the contributions library

achievements make to the broader community. Whilst there are many ways of

defining value, Oakleaf (2010) identifies the two main approaches as financial

value and impact value. Menchaca (2014) argues that for measuring value in the

academic library, impact is the more important measure as it relates to

learning. As libraries engage with the online space and the embedding of

seamless resources, they face new challenges as users may no longer identify

that space with the library. Consequently, the need to demonstrate impact

becomes more crucial (Sputore, Humphries, & Steiner, 2015).

Studies support measuring

impact that aligns with university outcomes

(Brown & Malenfant, 2012; Oakleaf, 2010; Pan et al., 2014). Library impact on institutional

outcomes of “student success, student achievement, student learning, and student

engagement” can be explored through evidence based practice (Oakleaf, 2010, p.

12). As mentioned in the literature, links, although not always causal, have

been examined between library usage and student outcomes such as attainment,

recruitment, and retention (Haddow, 2013; Hubbard & Loos, 2013; Soria,

Fransen, & Nackerud, 2013, 2014; Stone & Ramsden, 2013). Gathering

data, analyzing it, and presenting findings can demonstrate to academic faculty

that collaborating with library staff is worthwhile and can contribute to

student outcomes, thus creating library value (Oakleaf, 2010). As impact and

value are so closely linked, this allows establishment of not only value for

the Module but broader academic community library value (Bausman et al., 2014;

Bonfield, 2014; Brown & Malenfant, 2012; Creaser & Spezi, 2012;

Menchaca, 2014; Oakleaf, 2010; Pan et al., 2014; Tenopir, 2011).

“Information and

Documentation: Methods and Procedures for Assessing the Impact of Libraries,

ISO16439” (ISO, 2014) provides an internationally

recognised basis for assessing library impact (Henczel,

2014). The standard describes effects such as “changes in skills and

competence” and “higher success in research, study or career” (ISO, 2014, p. 14) as demonstrating library

impact. In addition, collaboration between library and academic staff for

embedding library resources in courses can also affect library impact through

changes in attitudes and behaviour (ISO, 2014).

Combining methods can provide a fuller or richer story for assessing impact,

but may also need more detailed analysis, as the findings from different source

data may not be consistent (ISO, 2014).

Henczel (2014, Sept.) provided a diagrammatic interpretation of the standard

methods and procedure for assessing the impact of libraries (Figure 1).

At Griffith University,

Lizzio’s (2006, 2011) Five Senses of Success framework has been used as a

predictor of student outcomes. This framework examines students’ success as

depending on their sense of capability, connection, purpose, resourcefulness,

and identity, and is particularly useful as it facilitates “conscious and

reflective practice” and forms a basis for student engagement strategies for

the broader Griffith University community (Wilson, 2009, p. 7). A sense of

resourcefulness and capability can be promoted if students can find the

information they need and are prepared for assignment tasks at university level

(Lizzio, 2011; Wilson, 2009). A sense of connection is encouraged by the

quality of relationships that are formed at university with peers, staff and

the affiliation with their school (Lizzio, 2011; Wilson, 2009). As strengths

and talents are developed and students learn how things are done at university, a sense of purpose and

identity are fostered (Lizzio, 2011; Wilson, 2009). Initially, the Five Senses of Success framework was

introduced to support student retention and engagement within the first year,

but this has been expanded to incorporate the whole student lifecycle (Lizzio,

2011). The use of the Five Senses of Success framework to examine the student

experience is supported in other studies that evaluate student support and

engagement, and adds metrics that are meaningful outside of the library environment

(Burnett & Larmar, 2011; Chester, Burton, Xenos, & Elgar, 2013;

Hutchinson, Mitchell, & St John, 2011; Sidebotham, Fenwick, Carter, &

Gamble, 2015). The Five Senses of Success framework indicators can be aligned

with those characteristics that have been previously used to evaluate

e-learning programs, such as usability, content richness, flexibility, and

learner community (Chiu, Hsu, Sun, Lin, & Sun, 2005; Lu & Chiou,

2010; Wang, 2003).

Figure

1

Henczel’s

(2014, Sept.) interpretation of impact assessment process based on ISO16439.

Figure 2

Impact assessment

process based on Henzcel’s (2014, Sept.) interpretation.

Aim

The aim of this paper is to

assess the impact of embedding an online academic and information literacy

resource into a first year business course. Measuring the impact will not only

determine whether the resource created and provided to students made any

difference to their success, but also demonstrate academic library value.

Methods

Drawing on measures and

methods identified in ISO16439 (2014), evidence was collected and combined from

a variety of sources over semester 2, 2014, and semester 1, 2015 to assess the

impact of the Module on student success.

Using ISO16439 (2014) as

interpreted by Henczel (2014, Sept.)

(Figure 2), an impact objective was established to discover if the Module

contributed to student success. This objective was aligned with impact

indicators based on Lizzio’s (2006, 2011) Five Senses of Success

framework of capability, connection, purpose, resourcefulness, and identity.

Inferred and solicited evidence was collected to support and explore those

indicators.

Inferred evidence was

gathered from usage statistics (number of hits on the Module), and from

performance measures (comparing student essay grade between those that did and

did not use the Module). Solicited evidence was gathered from a survey of

students, students in focus groups, and interviews with other stakeholders such

as course lecturers, tutors, and educational designers.

Inferred Evidence

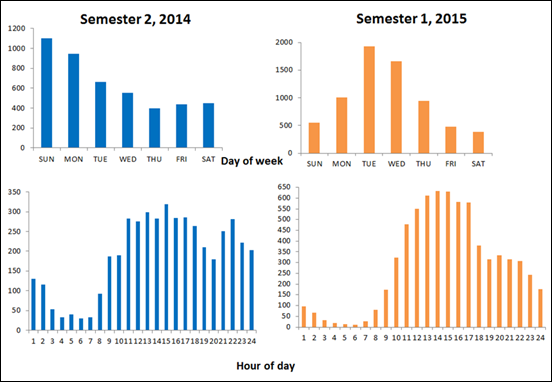

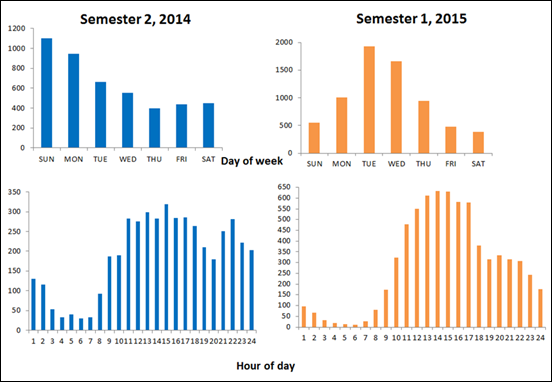

Statistics tracking in the

learning management system was activated for the Module for both semester 2, 2014

and semester 1, 2015. Usage data for day and time of access to the Module was

also available from the learning management system, Blackboard. Usage data

was matched to assessment grades from the Grade Center and the results analyzed

using Microsoft Excel.

Solicited Evidence

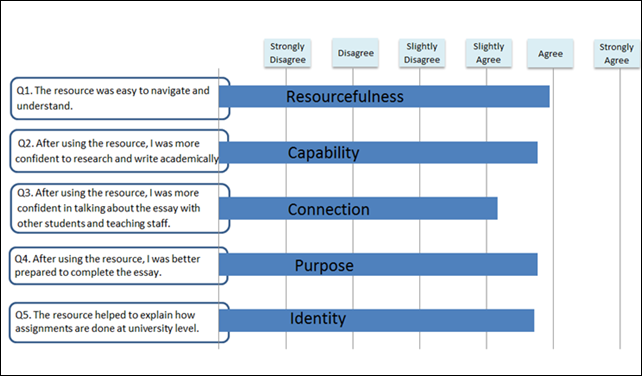

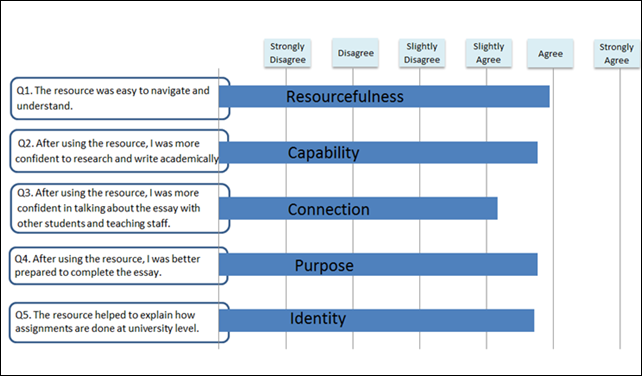

Following a pilot survey in

semester 2, 2014, a student survey was conducted in semester 1, 2015 with an

announcement and link to the survey placed in the learning management system,

Blackboard. The survey contained basic demographic questions, five response

scale questions, and one open ended question for comments. An even number

of options for the response scale questions ranging from strongly agree to

strongly disagree was used to remove the undecided or neutral response (ISO, 2014).

Each of the five response scale questions was designed to address one of

Lizzio’s (2011) Five Senses of Success (Table 1).

Table 1

Survey Questions

|

Survey Questions

|

Five Sense of Success (Lizzio, 2011)

|

|

1. The resource was easy

to navigate and understand.

|

- Resourcefulness; did the Module help

students to find information they need?

|

|

2. After using the

resource, I was more confident to research and write academically.

|

- Capability; did the Module help

students to prepare for tasks at university?

|

|

3. After using the

resource, I was more confident in talking about the essay with other students

and teaching staff.

|

- Connection; did the Module help

students to engage with peers, academic staff and support staff?

|

|

4. After using the

resource, I was better prepared to complete the essay.

|

- Purpose; did the Module help students

to develop strengths and talents?

|

|

5. The resource helped to

explain how assignments are done at university level.

|

- Identity; did the Module help students

to learn how things are done as a business student at university?

|

Two focus groups were held

during face to face tutorial time: 15 students in the first focus group and 18

students in the second group. Students were asked if they had used the Module

and what they found useful about it.

Stakeholder interviews were

conducted and an email was sent to the lecturer, tutors, and educational

designer with the following five questions:

- Did you refer to any sections of the Module in your tutorial

sessions?

- What was your impression of it?

- Did any of your students comment on it?

- If so, what did they say?

- Do you have any suggestions as to how to improve on it?

Results

Inferred Evidence

Inferred evidence data

collection was from spreadsheets within the learning management system which

were collated with spreadsheets from the Grade Center. Although a time

consuming process, the online data collection resulted in a clearer picture of

how students accessed and returned to the Module, and matching usage with

student essay assignment grades offered clearer information than could be

gleaned from evaluating face to face teaching sessions.

Usage data

As presented in Table 2, the

Module was accessed 4,442 times in semester 2, 2014.

Table 2

Module Usage Statistics

|

Semester 2 2014

|

Semester 1 2015

|

|

No. of students enrolled

|

1,023

|

784

|

|

Hits to Module

|

4,442

|

6,537

|

|

No. of students who

accessed Module (unique hits)

|

910

(89%)

|

750

(96%)

|

|

Average number of hits by

students who used the Module

|

4.88

|

8.72

|

|

% of students who used

the Module >once

|

90%

|

95%

|

For individual students,

this varied from not accessing the resource at all to accessing the resource 29

times. In 2014, 89% of the students accessed the resource, increasing to

96% in 2015. The average number of hits to the resource per student was 4.88,

indicating that students did find value in the resource, as they went back to

it multiple times. In semester 1, 2015, the Module was accessed 6,537 times,

varying from accessing the resource once to accessing the resource 37 times.

The average number of hits to the resource per student was 8.72.

Usage data for day and time of access to the Module

(Figure 3) highlights the 24/7 availability of the Module. The Module was used

on all days of the week and at all hours of the day.

Figure

3

Module

usage statistics: days of week and hour of day access.

Performance results

Comparing the average essay grade for those students

who used and those students who did not use the Module (Table 3) indicates that

use of the resource achieves a higher than average mark. In semester 2, 2014,

the average class essay grade was 64%, those who used the Module acquired a

slightly higher than average grade of 65%, and for those who did not use the

Module the average grade was 47%. For semester 1, 2015, the average class grade

was 58%, with those who used the Module receiving 61% and those who did not use

the Module receiving on average 15%. This larger difference in 2015 between

users and non-users of the Module could be attributed to the much higher usage

of the Module in 2015. A high percentage of students (96%) accessed the Module

in 2015. The remaining 4% who did not may represent the lesser engaged

students.

Table 3

Comparison of Module Usage

and Assignment Grade

|

Semester 2, 2014

|

Semester 1, 2015

|

|

Average essay grade

|

16/25

(64%)

|

17.5/30

(58%)

|

|

Average essay grade those

who used the Module

|

16.25/25

(65%)

|

18.2/30

(61%)

|

|

Average essay grade those

who did not use the Module

|

11.7/25

(47%)

|

4.5/30

(15%)

|

Solicited Data

Solicited

evidence collection tended to be better facilitated by a face to face approach.

The online survey did not reveal as much information as the face to face focus

groups.

Survey

The median survey response to all questions was

between “slightly agree” and “agree,” indicating that the Module contributed to

student success, as shown in Figure 4. This was supported by survey comments,

in particular “I was feeling quite overwhelmed by the task of writing the

essay, however after using the research and writing tool I feel a lot more

confident and at ease as I have a better understanding of how to approach the

task. Thank you.”

Figure 4

Survey results.

However, the number of

responses to the survey was low (42 responses, of which 35 used the Module) and

hampered by institutional policy on survey timing. This meant that the survey

had to be concluded the same day as the essay assignment was due, limiting

student reminders. It is worth noting that surveys as a method of

gathering evidence in the academic or institutional environment for evaluation

of assessment items needs to be carefully considered within the larger

institutional environment due to conflicting survey priorities. Even though

response rates were low, the data from the survey adds to the overall picture

of assessing the Module and highlights the advantages of a combined methods

analysis.

Focus groups

Overall, the focus group discussions were positive.

For those students who did use the resource, they found the Module easy to

navigate, particularly with the table of contents, as students could easily

select the topics that were most useful to them. Of the eight topics, those

rated as most useful were “Writing the report” and “Referencing,” although

others found the searching topics useful as they were unsure of search terms.

Other comments included “Had no idea what to do and resource gave me lots of

ideas of what to do,” “Helped clarify the questions,” and “Video format easy to

watch.” Two students did not watch the videos as they preferred to use the

transcript, which highlights the need to consider different learning styles.

The most frequent reason given

for not using the Module was that they did not know it was there, which

highlights the importance of collaboration for support and promotion from

academic staff. Interestingly, students responded that they had not used the

Module even though topics had been shown during tutorial time. This highlighted

the problem of assessing the impact of a highly embedded resource when students

assumed that it was just another teaching tool of the course and did not

associate it with being provided by the library.

Stakeholder

interviews

Tutors reported via the course convenor that they

received fewer than usual academic and information literacy questions about the

essay assignment from students, and the “Students said they found the videos

helpful and came to see me to clarify points in relation to their essay.”

Tutors’ comments below highlight the use of the

Module as a teaching tool:

“I can

report that the Research and Writing for Business Students Module on the course

website were a valuable learning and teaching tool. I referred to every section

of it during tutorials/workshops leading up to the due date for the submission

of the essay.”

“The

short video clips were generally very good and I received overwhelmingly

positive feedback from my student cohort.”

Some tutors mentioned that whilst the Module was

embedded into the tutorial and videos scheduled at various points in the

semester, technical issues on numerous occasions prevented the videos from

being played.

Tutors’ comments also highlighted the timesaving

benefits of the Module for tutors:

“The

fact that the resources are all together is handy for students and helpful to

tutors who have limited time allocated in class to develop students

"basic" writing skills. The students can choose to access the support

tools/information whenever, wherever, however many times they like.”

“In responding

to queries from students about an aspect of their research or writing process,

I was able to direct them to the relevant resource in addition to providing my

own guidance by e-mail or in person.”

One suggested improvement “Would be to make the

video clips more concise to hold students attention. This could perhaps be

achieved by using more focused and direct language.”

The educational designer has since shown the Module

to other interested academics and commented that:

“The

quality and value pretty much speaks for itself. Academics like that it's

co-located in the Assessment folder so it's easy for students to find and it's

contextual. They like that it's similar to what is taught into a course

on-campus, but it's online... which means students can access it whenever they

like, when they need it, as they are doing their assignments... they can see

that it will lead to fewer questions for them!”

Discussion

Gathering the data to support the impact objective

was made easier with the use of the framework offered by ISO16439 (2014) for assessing library impact, in

conjunction with the indicators offered by the Five Senses of Success framework

(Lizzio, 2011). Using this multifaceted approach to data collection, as

recommended by the standard, allowed for a fuller picture to be drawn.

The inferred evidence showed a positive impact. The

usage results indicate that the Module added to the student sense of

resourcefulness and capability; they were assisted in finding the right sorts

of information they needed at the right time (Lizzio, 2011). The high number of

repeat visits to the Module at various times of the day indicates that students

found the Module of assistance in writing and researching for their

assignment. The increase in usage over the semesters may highlight the

uptake of the Module as a teaching tool by teaching staff. The high number of

average hits to the Module per student indicates the library’s engagement with

the students enrolled in these courses. Linking this back to student success,

this high usage could be interpreted as the Module contributing to the

resourcefulness and capability of students in engaging them in the learning

process in assignment preparation and research (Lizzio, 2011).

The performance measures indicate that the Module

added to the students’ sense of capability; they were more able to complete the

assignment to satisfactory levels if they had used the Module (Lizzio, 2011).

Matched with the high usage rates, these performance statistics could indicate

that those students who used the Module were more engaged with the course.

The solicited evidence suggests that students saw

the Module in a positive light and that staff were happy with the impact it had

on students’ work and learning. The student survey and focus groups gave some

indication that students found a sense of purpose and identity in their

preparation (Lizzio, 2011). Their comments and survey responses supported that

they were learning how to research and write for their assignment task, as well

as how things were done at university (Lizzio, 2011). The interviews with

stakeholders gave a sense of promoting connection, that students were part of

their learning process and were able to access help from the Griffith

University community (Lizzio, 2011).

Assessing the impact of the Module provides the

opportunity to reflect on practice. From feedback it was evident that some

structural changes need to be made to the Module to make it more targeted and

direct. Looking at the Module from the student’s viewpoint and also the

environment into which it has been embedded has made it clear that any topic

which was not assessment focused needs to be re-examined. The necessity of

collection and analysis of data is highlighted by the fact that Module usage

may not correspond with student identification of assistance from a learning

adviser or librarian, as the resource for assignment assistance is so embedded

into the course. This indicates an area for further study, as highlighted by

Sputore et al. (2015). However, the evidence collected does provide support for

continuing collaboration using the four-pronged collaboration model between

librarians, learning advisers, academics, and educational designers in the

production of these embedded online assessment based resources (Gunn et al.,

2011).

The assessment of the Module enabled the alignment

of library practices to institutional strategic and operational plans through

collaboration and building partnerships with academics, learning advisers, and

educational designers. It has helped to demonstrate the library’s

contribution to the achievement of Griffith University’s strategic changes,

such as meeting operational plans of a fully online, seamless student model and

meeting opportunities presented by changes to teaching semesters.

Using a combination of ISO16439 (2014) with Henczel’s (2014, Sept.) diagrammatic

interpretation of the standard and Lizzio’s (2006, 2011) Five Senses of Success

framework may be beneficial to other academic libraries and the broader library

community wishing to engage in evidence based practice to measure library

impact that aligns to institutional outcomes. For other libraries, different

impact objectives and indicators more relevant to their institutional outcomes

may be more beneficial in assessing impact.

Engaging in this research has provided the

opportunity to document procedures and practices surrounding data gathering,

analyzing, and reporting. Documenting the process is valuable to establish a

library connection to institutional outcomes, and worth considering for any

libraries wishing to engage in evidence based practice.

Conclusions

Overall, the evidence showed that over 90% of

students accessed the online resource “Research and Writing for Business Students,”

and it was well received by both staff and students. Students have stated that

it gave them the confidence to get started on their assignments, and academic

staff commented that it decreased the amount of generic questions they received

about the assignment. Using the criteria of the Five Senses of Success (Lizzio,

2006, 2011) as impact indicators, it is believed that the gathered evidence

indicates the Module did achieve the impact objective of a positive impact on

the contribution to student success for these first year business students.

Assessing the impact of the online resource

“Research and Writing for Business Students” on student success has helped to

demonstrate the value of the library at Griffith University to the wider

community. The Business Library and Learning team at Griffith University moved

its teaching practice into the online environment, but did not lose relevance

in supporting students. The four-pronged collaboration relationship required

for this approach was fostered with stakeholders outside of the library.

References

Association of

College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Research Planning and Review Committee.

(2014). Top trends in academic libraries: A review of the trends and issues

affecting academic libraries in higher education. College & Research Libraries News, 75(6), 294-302. Retrieved from http://crln.acrl.org/content/75/6/294.full.pdf+html

Bausman, M., Ward, S. L., &

Pell, J. (2014). Beyond satisfaction:

Understanding and promoting the instructor-librarian relationship. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 20(2),

117-136. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2014.911192

Bonfield, B.

(2014). How well are you doing your job? You don’t know. No one does. In the Library with the Lead Pipe.

Retrieved from http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2014/how-well-are-you-doing-your-job-you-dont-know-no-one-does/

Brown, K., & Malenfant, K. J. (2012). Connect,

collaborate, and communicate: A report from the value of academic libraries

summits. Chicago, IL:

Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/value/val_summit.pdf

Burnett, L.,

& Larmar, S. (2011). Improving the first year through an institution-wide

approach: The role of first year advisors. The

International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 2(1), 21-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v2i1.40

Chester, A., Burton, L. J.,

Xenos, S., & Elgar, K. (2013). Peer

mentoring: Supporting successful transition for first year undergraduate

psychology students. Australian Journal

of Psychology, 65(1), 30-37. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ajpy.12006/epdf

Chiu, C. M., Hsu, M. H., Sun, S. Y., Lin, T. C., & Sun,

P. C. (2005). Usability, quality, value and e-learning continuance decisions. Computers & Education, 45(4),

399-416. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2004.06.001

Creaser, C.,

Cullen, S., Curtis, R., Darlington, N., Maltby, J., Newall, E., & Spezi, V.

(2014). Working together: Library value at the University of Nottingham. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 15(1/2),

41-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/PMM-03-2014-0011

Creaser, C.,

& Spezi, V. (2012). Working together:

Evolving value for academic libraries. Retrieved from http://libraryvalue.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/ndm-5709-lisu-final-report_web.pdf

Creaser, C., & Spezi, V. (2014).

Improving perceptions of value to teaching and research staff: The next

challenge for academic libraries. Journal

of Librarianship and Information Science, 46(3), 191-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0961000613477678

Einfalt,

J., & Turley, J. (2009). Engaging first year students in skill development:

A three-way collaborative model in action. Journal

of Academic Language and Learning, 3(2), A105-A116. Retrieved from

http://journal.aall.org.au/index.php/jall/article/view/87/73

Einfalt,

J., & Turley, J. (2013). Partnerships for success: A collaborative support model

to enhance the first year student experience. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 4(1),

73-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v4i1.153

Gibson, C.,

& Dixon, C. (2011). New metrics for academic library

engagement. In D. M. Mueller (Ed.), A

Declaration of Interdependence - ACRL Conference March 30–April 2, (pp.

340-351). Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved

from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/national/2011/papers/new_metrics.pdf

Gunn,

C., Hearne, S., & Sibthorpe, J. (2011). Right from the start: A rationale

for embedding academic skills in university courses. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 8(1), 1-10.

Retrieved from http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1159&context=jutlp

Haddow, G. (2013). Academic library use and student retention: A

quantitative analysis. Library &

Information Science Research, 35(2), 127-136. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2012.12.002

Henczel,

S. (2014). The impact of library associations: Preliminary findings of a

qualitative study. Performance

Measurement and Metrics, 15(3), 122-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/PMM-07-2014-0025

Henczel,

S. (2014, Sept.). Library Metrics

Workshop. Presented at Griffith University, Brisbane, Queensland,

Australia, September 12, 2014.

Hubbard, M. A., & Loos, A. T. (2013). Academic

library participation in recruitment and retention initiatives. Reference Services Review, 41(2),

157-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907321311326183

Hutchinson,

L., Mitchell, C., & St John, W. (2011). The transition experience of

enrolled nurses to a bachelor of nursing at an Australian university. Contemporary nurse, 38(1-2), 191-200. http://dx.doi.org/10.5172/conu.2011.38.1-2.191

International

Organisation for Standardisation. (2014). Information

and documentation: Methods and procedures for assessing the impact of

libraries, ISO16439. Retrieved from http://saiglobal.com

Johnson,

L., Adams Becker, S., Estrada, V., & Freeman, A. (2014). NMC Horizon report: 2014 higher education

edition. Austin, TX: The New Media Consortium. Retrieved from http://cdn.nmc.org/media/2014-nmc-horizon-report-he-EN-SC.pdf

Kokkinn, B.,

& Mahar, C. (2011). Partnerships for

student success: Integrated development of academic and information literacies

across disciplines. Journal of Academic

Language and Learning, 5(2), A118-A130. Retrieved from

http://journal.aall.org.au/index.php/jall/article/view/170/115

Kranich, N., Lotts, M., & Springs,

G. (2014). The promise of academic libraries: Turning outward to transform

campus communities. College &

Research Libraries News, 75(4), 182-186. Retrieved from http://crln.acrl.org/content/75/4/182.short

Lizzio,

A. (2006). Designing an orientation and transition strategy for commencing

students: A conceptual summary of research and practice. Griffith University first year experience project. Retrieved from http://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/51875/Alfs-5-Senors-Paper-FYE-Project,-2006.pdf

Lizzio,

A. (2011). Succeeding@ Griffith: Next generation partnerships across the

student lifecycle. In Griffith University

Student Lifecycle, Transition and Orientation. Retrieved from http://www.griffith.edu.au/learning-teaching/student-success/first-year-experience/student-lifecycle-transition-orientation

Lu, H. P.,

& Chiou, M. J. (2010). The impact

of individual differences on e-learning system satisfaction: A contingency approach. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 41(2), 307-323. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.00937.x

Menchaca,

F. (2014). Start a new fire: Measuring the value of academic libraries in

undergraduate learning. portal: Libraries

and the Academy, 14(3), 353-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2014.0020

Nelson,

K. (2014). The first year in higher education-Where to from here? The International Journal of the First Year

in Higher Education, 5(2), 1-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v5i2.243

Oakleaf,

M. (2010). The value of academic

libraries: A comprehensive research review and report. Chicago, IL:

Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/value/val_report.pdf

Pan,

D., Ferrer-Vinent, I. J., & Bruehl, M. (2014). Library value in the

classroom: Assessing student learning outcomes from instruction and

collections. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 40(3–4), 332-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.04.011

Sidebotham,

M., Fenwick, J., Carter, A., & Gamble, J. (2015). Using the five senses of

success framework to understand the experiences of midwifery students enroled

in an undergraduate degree program. Midwifery,

31(1), 201-207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2014.08.007

Soria, K. M., Fransen, J., &

Nackerud, S. (2013). Library use and undergraduate student outcomes: New

evidence for students' retention and academic success. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 13(2), 147-164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2013.0010

Soria, K. M., Fransen, J., &

Nackerud, S. (2014). Stacks, serials, search engines, and

students' success: First-year undergraduate students' library use, academic

achievement, and retention. The Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 40(1), 84-91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.12.002

Sputore, A., Humphries, P., & Steiner, N. (2015). Sustainable

academic libraries in Australia: Exploring ‘radical collaborations’ and

implications for reference services. Paper presented at IFLA WLIC, 15-21 August, 2015, Cape Town, South

Africa. Retrieved from http://library.ifla.org/1078/1/190-sputore-en.pdf

Stone, G., & Ramsden, B. (2013). Library impact

data project: Looking for the link between library usage and student

attainment. College & Research

Libraries, 74(6), 546-559. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl12-406

Taib,

A., & Holden, J. (2013). "Third generation" conversations: A

partnership approach to embedding research and learning skills development in

the first year. A practice report. The International

Journal of the First Year in Higher Education, 4(2), 131-136. http://dx.doi.org/10.5204/intjfyhe.v4i2.178

Tenopir,

C. (2011). Beyond usage: Measuring library outcomes and value. Library Management, 33(1/2), 5-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01435121211203275

Thies,

L., Wallis, A., Turner, A., & Wishart, L. (2014). Embedded academic

literacies curricula: The challenges of measuring success. Journal of Academic Language & Learning, 8(2), 43-59. Retrieved

from http://dro.deakin.edu.au/eserv/DU:30064956/thies-embeddedacademic-2014.pdf

Tinto,

V. (2005 January). Taking student success seriously: Rethinking the first year

of college. In Ninth Annual Intersession

Academic Affairs Forum, California State University, Fullerton, 05-01.

Retrieved from http://www.hartnell.edu/sites/default/files/Library_Documents/bsi/V%20Tinto%20retention.pdf

Wang, Y. S. (2003). Assessment of learner satisfaction

with asynchronous electronic learning systems. Information & Management, 41(1), 75-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(03)00028-4

Wilson,

K. (2009 June). The impact of

institutional, programmatic and personal interventions on an effective and

sustainable first-year student experience. Presented at the 12th Pacific

Rim First Year in Higher Education Conference, Preparing for Tomorrow Today:

The First Year Experience as Foundation. Townsville, Australia. Retrieved from https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/409084/FYHE-2009-Keynote-Keithia-Wilson.pdf

![]() 2015 Rae and Hunn. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Rae and Hunn. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.