Introduction

The purpose of reference services in academic libraries has always been

to help users with their research endeavors. The manner in which help is

provided differs from institution to institution and has evolved over time.

Literature shows that in order to provide library patrons with help and

guidance, librarians in most academic institutions have been transitioning away

from a service point, such as the reference desk, into more specialized and

advanced assistance through referrals made by library support staff (Arndt,

2010), or by

the delivery of individualized consultation services to users. Studies have

shown that staffing reference desks or one-point service desks with library

support staff has been efficient; one study determined that 89% of questions

could be efficiently answered by non-librarians (Ryan, 2008).

Individualized research consultation (IRC) services have had many names

over the years: “term paper clinics”, “term paper counseling”, “research

sessions”, “term paper advisory service”, “personalized research clinics”,

“research assistance programs”, “individualized instruction” and so on. Essentially,

an IRC is a one-on-one instructional session between a librarian and a user in

order to assess the user’s specific research needs and help them find

information. While group instruction is a great way to introduce students to various

library skills, individual research consultations allow for more in-depth

questions that are specific to a student’s information needs. One advantage

that this type of service provides over traditional reference services is that

it gives “students the individualized attention and serves them at their points

of need” (Yi, 2003, p. 343).

Aim

Academic

librarians can spend many hours helping individuals with their research

projects. While research has examined the ways in which information literacy

(IL) skills have been taught in the classroom, research conducted for

one-on-one consultations is reported less frequently. With this observation, a

scoping review seemed appropriate to further enhance our knowledge of IRC

assessment methods. As Arksey and

O'Malley (2005) stated:

Scoping studies might aim to map rapidly the key concepts

underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence

available, and can be undertaken as stand-alone projects in their own right,

especially where an area is complex or has not been reviewed comprehensively

before. (p. 21)

Colquhoun

et al. (2014) further formalize the definition of scoping reviews:

A scoping review or scoping study is a form

of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question aimed at

mapping key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research related to a

defined area or field by systematically searching, selecting, and synthesizing

existing knowledge. This definition builds on the descriptions of Arksey and O’Malley, and Daudt to

provide a clear definition of the methodology while describing the key

characteristics that make scoping reviews distinct from other forms of

syntheses. (p.1292)

This scoping review attempts to answer the following question: Which evaluation methods are used to measure impact and

improve individualized research consultations

in academic libraries?

Method

Researchers conducted a systematic search of the following databases for

the years 1990-2013: Library and Information Science Abstracts (LISA), Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC), Library and

Information Technology Abstracts (LISTA), Scopus, and Web of Science. Search

terms included: individual consultation, research consultation, one-on-one

consultations, research clinics, personalized research, and evaluation,

assessment, impact, with combinations of these terms. Researchers used the

thesauri of individual databases alongside keyword searching.

Using a manual search of the included articles’ reference lists, the

authors located additional relevant articles. Some articles were found while searching

the reference lists, dating back further than our original search date range.

As they were key first articles on the topic and answered our inclusion

criteria, we decided to keep them. Due to constraints with acquiring proper

translation, we only included articles written in English or French, with

English abstracts of articles in other languages assessed, if available. We searched

Google Scholar for online grey literature in hopes of locating unpublished

studies and other reports exploring individualized research consultations, with

little additional information found.

We included descriptive articles, qualitative and quantitative studies,

single case studies, and review articles if they discussed evaluating or

assessing individual consultations. We excluded book chapters, policy papers

and documents, commentaries, essays, and non-published theses, as these types

of documents did not address evaluating/assessing IRCs as primary studies. We

included articles that discussed individualized research consultations at the

undergraduate or graduate level, included some form of evaluation or

assessment, and were based within a library setting. We excluded articles that

discussed group instruction, were not included in a library setting (such as

consultation for profit), and which did not include any form of evaluation or

assessment.

Both authors conducted data collection and synthesis, and collectively

wrote the background, conceptualized the review, undertook the searches, and

screened the articles. We each screened the articles, and then compared. We

discussed disagreements between the inclusion and exclusion of the articles,

and reached a decision for each situation. We both synthesized the data and

crafted the findings.

Data collected from the reviewed articles included aims of the studies,

type of evaluation/assessment involved, procedures and methods used, audience

level (e.g., undergraduate, graduate, faculty, etc.), and main findings.

Results

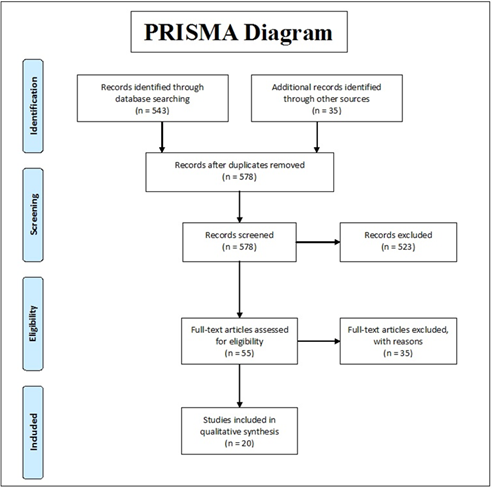

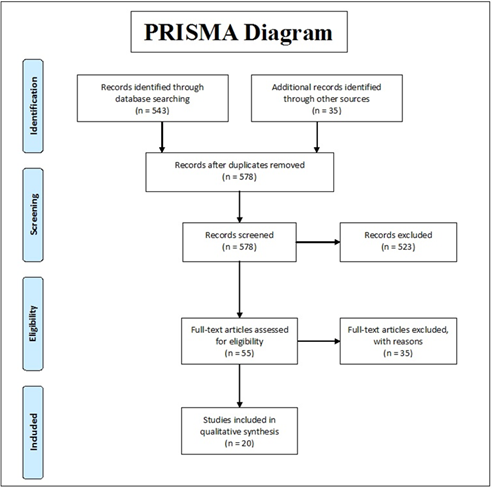

The modified PRISMA flow chart (Moher,

Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009) in Figure 1

demonstrates the number of articles and results from the selection and

screening process. Researchers identified 543 potential articles through

database searching (after duplicates removed), and found an additional 35

articles through cited reference searching of the references lists of the

included articles. All titles and abstracts were reviewed, and 523 of the

articles did not include any form of evaluation, or mention individual

consultations, and were therefore excluded. We examined full text sources of

the remaining 55 articles against inclusion and exclusion criteria, leaving 20

articles for our qualitative synthesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Modified PRISMA flow chart

Qualitative thematic analysis

This section presents the analysis of the 20 included articles’

extracted data, which are compiled and organized in Table 1 for rapid review.

An in-depth overview of each study is available in the Appendix.

Table 1

Assessment Methods and Included Articles

|

Assessment Methods

|

Usage Statistics

|

Survey

|

Objective Quantitative Methods

|

|

Included Articles

|

Attebury,

Sprague, & Young, 2009

|

Auster, Devakos,

& Meikle, 1994

|

Erickson & Warner, 1998

|

|

Becker,

1993

|

Bean,

1995

|

Donegan, Domas,

& Deosdade, 1989

|

|

Hoskisson &

Wentz, 2001

|

Cardwell, Furlong, &

O'Keeffe, 2001

|

Reinsfelder, 2012

|

|

Lee, 2004

|

Coniglio, 1984

|

|

|

Meyer, Forbes, & Bowers, 2010

|

Debreczeny, 1985

|

|

Yi, 2003

|

Gale

& Evans, 2007

|

|

|

Gratch &

York, 1991

|

|

Imamoto, 2006

|

|

Magi & Mardeusz,

2013

|

|

Rothstein,

1990

|

|

Schobert, 1982

|

|

Total

|

6

|

11

|

3

|

We grouped articles into three overall types of assessment methods:

usage statistics, survey, or

objective quantitative methods. Table 1 lists the

assessment methods with their affiliated articles. These categories were

inspired by Attebury, Sprague and Young (2009), who

previously classified such articles in two main categories: “Surveys as

evaluation tools have been a popular means of assessment […] while for other

authors analysis of statistics and writing about their program has served as a

useful mean of evaluation” (p. 209).

Table 2 summarizes the specific methods of assessment, which articles

they are correlated with, and the number of students surveyed/tested, if

applicable. Where usage statistics were used, the type of statistics gathered

include number of students encountered, number of hours or sessions provided,

librarian’s preparation time, length of the meeting, student’s affiliation

(e.g., department or program), reason for requesting an appointment (e.g.,

course-related, paper, dissertation, etc.), and student’s gender. When a survey

was used, methods included the use of an evaluation form completed by patrons

following the appointment, surveys sent to users of the service weeks or months

later, and use of an evaluation form completed by the service’s provider (e.g.,

librarian, MLS student). When the assessment was via an objective quantitative

method, all three articles developed their own unique assessment methods to

evaluate individual research consultations. In these cases, the methods all

include a certain level of objectivity, as opposed to the more subjective

nature found with assessment using surveys. The methods included assessment of

assigned database searches performed by the patron, information literacy skills

test (multiple choice questions), and citation analysis of the draft and final

papers’ bibliographies from the students.

Table 2

Specific Methods of Assessment Used

|

Assessment

Methods

|

Specific

methods of assessment

|

Articles

|

No. of

students surveyed or tested

|

|

Usage statistics

|

1.

Usage

statistics compilation

Stats

acquired:

|

n/a

|

|

No. of students

seen

|

Attebury, Sprague, & Young, 2009

|

|

Yi, 2003

|

|

No. of hours or

sessions provided

|

Attebury,

Sprague, & Young, 2009

|

|

Becker,

1993

|

|

Hoskisson &

Wentz, 2001

|

|

Lee, 2004

|

|

Meyer, Forbes, & Bowers, 2010

|

|

Yi, 2003

|

|

Librarian’s

preparation time

|

Attebury,

Sprague, & Young, 2009

|

|

Lee, 2004

|

|

Length of meeting

|

Attebury,

Sprague, & Young, 2009

|

|

Yi, 2003

|

|

Student

affiliation (dept., or program)

|

Lee, 2004

|

|

Reason

for request (course-related, paper, dissertation, etc.)

|

Attebury, Sprague, &

Young, 2009

|

|

Yi, 2003

|

|

Student’s

gender

|

Attebury, Sprague, &

Young, 2009

|

|

Survey

|

1.

Evaluation form filled by patrons after individual

consultation

|

Auster, Devakos, & Meikle,

1994

|

39

|

|

Bean,

1995

|

27

|

|

Gale & Evans, 2007

|

23

|

|

Magi & Mardeusz,

2013

|

52

|

|

Imamoto, 2006

|

95

|

|

Rothstein, 1990

|

77

|

|

2.

Surveys sent to users of the service weeks or months

later

|

Cardwell, Furlong, & O'Keeffe, 2001

|

16

25

|

|

Coniglio, 1984

|

57

|

|

Debreczeny, 1985

|

60

|

|

Gratch & York, 1991

|

17

|

|

Shobert, 1982

|

19

|

|

3.

Evaluation form to be filled by the service’s

provider (librarian, MLS student)

|

Auster, Devakos, & Meikle, 1994

|

n/a

|

|

Bean,

1995

|

45

|

|

Gale & Evans, 2007

|

n/a

|

|

Rothstein, 1990

|

n/a

|

|

Objective quantitative methods

|

1.

Assessment of assigned database searches performed

by the patron

|

Erickson

& Warner, 1998

|

31

|

|

2.

Information literacy skills test (multiple choice

questions)

|

Donegan, Domas, & Deosdade, 1989

|

156

|

|

3.

Citation analysis of students draft and final

papers’ bibliographies

|

Reinsfelder,

2012

|

103

|

Table 3

Populations that Used IRC Services per Assessment Method

|

Populations

|

No. of

articles using usage statistics

|

No. of

articles using a survey

|

No. of

articles using objective quantitative methods

|

Total no.

of articles

|

|

Undergraduate

students only

|

1

|

5

|

2

|

8

|

|

Graduate

students only

|

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

|

Undergraduate

et graduate students

|

5

|

5

|

|

10

|

|

Faculty

members or researchers (as an additional population)

|

3

|

1

|

|

4

|

Additionally, we have determined how many papers provided IRC services

to undergraduate students, graduate students, or both, along with faculty

members or researchers, as shown in Table 3. Many articles mentioned having a

specific population in mind when starting a service, but ended up serving

additional populations. Ten articles described serving both the undergraduate

and graduate population, and eight articles the undergraduate students only.

Two articles were evaluating a service offered to graduate students only.

Most of the articles included in the detailed analysis are not “studies”

per se, but rather a description of library services. Therefore, many of those

articles do not use the intervention/comparison/outcome format. Table 4 is an

attempt to categorize the extracted data using these categories, with the

presumption that this is an interpretation exercise. The intervention is the

assessment method used in the selected articles, the comparison is listed if used

in the included articles, and the outcome is an overall summary of the benefits

and outcomes for each assessment method.

Table 4

Interventions, Comparisons, and Outcomes

|

Intervention

|

Comparison

|

Outcome

|

|

Usage Statistics

|

N/A

|

Usage statistics

method allows for an in-depth analysis of how the service is used and can

contribute to decision-making for the future or the modification of the

service.

Anecdotal

comments are heavily used throughout the included articles and were a large

part of the service’ performance analysis.

|

|

Survey

|

N/A

|

Surveys were used to mainly acquire information on

users’ satisfaction. Other information of interest for survey’s creators

related to the service’s marketing, and users’ affiliation.

All of the included articles had positive feedback

(satisfaction level) from their users.

|

|

Objective Quantitative Methods:

Specific Interventions

|

|

Individualized Medline Tutorial

(Erickson &

Warner, 1998)

|

1) Group tutorial

2) Control group: No tutorial

|

No statistically significance differences were found

for the search duration, the quantity of articles retrieved, the recall, and

the precision rate. There were many limitations to the study,

such as a small group of participants, low compliance rates, and a change in

the database platform at the study’s mid-point.

Participants

felt satisfied with their searches, and were interested in improving their

MEDLINE search skills. The authors concluded that time constraints is a major

obstacle for information professionals to provide individual tutorials to

hundreds of residents, who themselves struggle to free some time from their

busy hospital schedule to receive adequate database search skills training.

|

|

Term Paper Counselling (TPC)

(Donegan, Domas, & Deosdade, 1989)

|

1) Group

instruction session

2) Control group:

No instruction

|

Statistically

significant differences appeared between TPC and the control group, and

between group instructions and the control group. No statically significant

differences were found between TPC and group instruction. The authors

concluded that either type of intervention (group or individual) is

appropriate when teaching basic library search skills.

|

|

Individualized Consultation

(Reinsfelder,

2012)

|

1) Control group: no consultation

|

Using citation analysis and comparing students’

draft and final papers using a rating scale allowed the author to run

nonparametric statistical tests. Statistically significant differences were

found between draft and final papers for the experimental group, but no

significant difference were found for the control group. The author concluded

that students benefited from an individualized consultation and showed an

improvement in their sources’ quality, relevance, currency, and scope.

|

Discussion

Several articles relied heavily on usage statistics

to assess their individualized research consultation (IRC) services. Whether

the number of students seen, or the number of hours librarians spent preparing

or providing the consultations, these statistics can tell us how this service

is used by the student population, but they do not describe the impact of such

services except when anecdotal comments from users are recorded. In addition to

usage statistics, Attebury, Sprague, & Young

(2009), as well as Yi (2003), gathered and analyzed information about the

content of IRCs. Yi noted that the most frequent themes discussed during an IRC

were “topic assistance”, “search skills”, and “database selection”, and these

are just some of the elements covered in class presentations. This suggests

that IRC could benefit from a better alignment with information literacy

standards to develop students’ information literacy skills. Overall, many

articles using this method mentioned the need to further the assessment of IRC

beyond usage statistical analysis. Attebury, Sprague

& Young (2009), mention their intention of collecting information on

student satisfaction to help evaluate and improve their service on a continuous

basis.

The set of articles relying on survey methods is

large, and some date back to the 1980’s. Most surveys or evaluation forms focus

on user satisfaction, and many authors suggest this gives an indication of the

success of the service provided and helps to adjust the service delivery if

needed. However, this is still based on user sense of satisfaction and not on

actual performance outcomes. Cardwell, Furlong & O’Keeffe (2001) indicate

that “because of the nature of [personalized research clinics], it is difficult

to truly assess student learning and isolate the long-term impact that an

individual session has on a student’s knowledge and skills” (p. 108). Also, as

stated by several authors, but well-phrased by Shobert

(1984), “evaluating a project like this objectively is nearly impossible. There

is a built-in bias in its favor: where there was nothing, suddenly there is an

individualized instruction program; the responses are bound to be positive”

(p.149). Whether it is a new service or not, providing tailored individual help

to students will always be appreciated, which skews user satisfaction in survey

results. Recently, Magi and Mardeusz (2013) surveyed

students on their feelings before and after the individual consultation, and

the comments they received demonstrate the value of individual consultation. It

relieves students’ anxiety, and instead of feeling overwhelmed, students felt

encouraged and more focused. The psychological well-being of students is less

frequently studied in relation to the impact of individual consultations, but

this study demonstrated a less obvious impact, one certainly worth mentioning

when it comes to the value of the time spent with students individually.

As stated earlier, Shobert

(1984) mentioned that it would be nearly impossible to objectively evaluate an

individual research consultation service. The three articles using objective

quantitative methods have attempted to do just that by measuring, in an

objective manner, the impact individualized research consultations have on student’s

information literacy skills. They all have taken different paths to evaluate

this impact. Results were unsuccessful in demonstrating a statistically

significant difference on the impact of individual consultation between group

instruction and term paper counselling (TPC) (Donegan, Domas, & Deosdade, 1989), and

between getting an individual tutorial or not (Erickson & Warner, 1998).

These authors explained that many reasons could account for these results, such

as low compliance at performing the tasks requested, and test validity and

reliability. In the Donegan, Domas,

and Deosdade (1989) study, results showed no

statistically significant difference between group instruction and term paper

clinics. This study focused on introductory material, such as that usually

taught in a first year undergraduate class. One could venture to say that basic

library skills can easily be provided to students in a group setting, and that

perhaps individual consultations are more appropriate for advance skills

development. Reinsfelder (2012) found a statistically

significant difference in his study, which he concludes “[provides] some

quantitative evidence demonstrating the positive impact of individual research

consultation” (p. 263). He also stated that “librarians were frequently able to

make more meaningful connections with students by addressing the specific needs

of each individual” (p. 275), which speaks to the very nature of

individual research consultations.

Our scoping

review was not without its limitations. Firstly, our review is only

descriptive, with limited information to quantify our findings. Further

research would be required to assess the impact of individualized research

consultations to correctly identify specific methods that increase the

searcher’s success. Secondly, none of the articles included in our study were

critically appraised, limiting the reproducibility, completeness, and

transparency of reporting the methods and results of our scoping review.

However, as there is already limited information available regarding IRCs, we

did not want to exclude any articles on the topic.

Future

research should focus on quantifying the impact of individualized research

consultations. As our scoping review demonstrates, we were only able to find

three studies that used objective quantitative assessment methods. Not only

will gathering more quantitative information further inform IRCs’ practices,

but it will also complement the descriptive information obtained from surveys

and usage statistics. It should be noted that there are different methods that

may need to be considered when examining IRCs between disciplines. Further

research should also examine these differences, attempting to find the best

methods for individual disciplines. Lastly, a more in-depth examination of the

evaluation of the quality of the studies that we found should be undertaken.

Conclusion

Our research question asked, which evaluation methods are used to

measure impact and improve IRCs in academic libraries? We were able to identify

usage statistics and surveys as the main methods of assessment used to evaluate

IRCs. In addition, three articles attempted to objectively and quantitatively

measure the impact of individual consultations. This amounts to very few

studies compared to the wealth of articles on the assessment of group

instruction.

Individual research consultations have been around for decades and help

students at various stages of their research activities. Providing this

personalized service one-on-one is time consuming for librarians, and should be

better acknowledged and assessed.

Future research should address the need for more objective assessment

methods of studies on IRCs. In combination with usage statistics and surveys,

objective quantitative studies would yield a greater quality of evaluation for

IRCs. Furthermore, as these evaluation methods become more valid, a closer

inspection of IRCs across disciplines could be explored with greater success.

References

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a

methodological framework. International

Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Arndt, T.

S. (2010). Reference service without the desk. Reference Services Review, 38(1), 71-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907321011020734

Attebury, R., Sprague, N., & Young, N. J. (2009). A decade of personalized

research assistance. Reference Services

Review, 37(2), 207-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320910957233

Auster, E., Devakos,

R., & Meikle, S. (1994). Individualized

instruction for undergraduates: Term paper clinic staffed by MLS students. College & Research Libraries, 55(6),

550-561. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl_55_06_550

Bean, R.

(1995). Two heads are better than one: DePaul University's research

consultation service. In C. J. Jacob (Ed.), The Seventh Off-Campus Library Services Conference Proceedings, (pp.

5-16). Mount Pleasant, MI: Central Michigan University. http://gcls2.cmich.edu/conference/past_proceedings/7thOCLSCP.pdf

Becker, K.

A. (1993). Individual library research clinics for college freshmen. Research Strategies, 11(4), 202-210.

Cardwell,

C., Furlong, K., & O'Keeffe, J. (2001). My librarian: Personalized research

clinics and the academic library. Research

Strategies, 18(2), 97-111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0734-3310(02)00072-1

Colquhoun, H. L., Levac,

D., O'Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C.,

Perrier, L., … Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time

for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291-1294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

Coniglio, J. W. (1984). Bibliographic counseling: The term paper advisory

service. Show-Me Libraries, 36(12),

79-82.

Debreczeny, G. (1985). Coping with numbers: Undergraduates and individualized term

paper consultations. Research Strategies,

3(4), 156-163.

Donegan, P. M, Domas, R. E., & Deosdade, J. R. (1989). The comparable effects of term

paper counseling and group instruction sessions. College & Research Libraries, 50(2), 195-205. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl_50_02_195

Erickson,

S. S., & Warner, E. R. (1998). The impact of an individual tutorial session

on MEDLINE use among obstetrics and gynaecology

residents in an academic training programme: A

randomized trial. Medical Education, 32(3),

269-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00229.x

Gale, C.

D., & Evans, B. S. (2007). Face-to-face: The implementation and analysis of

a research consultation service. College

& Undergraduate Libraries, 14(3), 85-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J106v14n03_06

Gratch, B. G., & York, C. C. (1991). Personalized research consultation

service for graduate students: Building a program based on research findings. Research Strategies, 9(1), 4-15.

Haynes, R.

B., McKibbon, K. A., Walker, C. J., Ryan, N., Fitzgerald,

D., & Ramsden, M. F. (1990). Online access to MEDLINE in clinical settings.

A study of use and usefulness. Annals of

Internal Medicine, 112(1), 78-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-112-1-78

Hoskisson, T., & Wentz, D. (2001). Simplifying electronic reference: A hybrid

approach to one-on-one consultation. College

and Undergraduate Libraries, 8(2), 89-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J106v08n02_09

Imamoto, B. (2006). Evaluating the drop-in center: A service for

undergraduates. Public Services

Quarterly, 2(2), 3-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J295v02n02_02

Lee, D.

(2004). Research consultations: Enhancing library research skills. Reference Librarian, 41(85), 169-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J120v41n85_13

Magi, T. J., & Mardeusz, P. E. (2013). Why some students

continue to value individual, face-to-face research consultations in a

technology-rich world. College &

Research Libraries, 74(6), 605-618. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl12-363

Meyer, E.,

Forbes, C., & Bowers, J. (2010). The Research Center: Creating an

environment for interactive research consultations. Reference Services Review, 38(1), 57-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907321011020725

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., &

Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and

meta- analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal

of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1006-1012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

Reinsfelder, T. L. (2012). Citation analysis as a tool to measure the impact of

individual research consultations. College

& Research Libraries, 73(3), 263-277. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl-261

Rothstein,

S. (1990). Point of need/maximum service: An experiment in library instruction.

Reference Librarian, 11(25/26),

253-284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J120v11n25_11

Ryan, S. M.

(2008). Reference transactions analysis: The cost-effectiveness of staffing a

traditional academic reference desk. Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 34(5), 389-399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2008.06.002

Schobert,

T. (1982). Term-paper counseling: Individualized bibliographic instruction. RQ, 22(2), 146-151.

Yi, H.

(2003). Individual research consultation service: An important part of an

information literacy program. Reference

Services Review, 31(4), 342-350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320310505636

Appendix

Descriptive

Summary Analysis of Included Articles

This appendix presents the included articles’ extracted data as an

in-depth review of each study, organized by the three categories used in this

review: usage statistics, survey, and objective quantitative methods.

Usage

Statistics

Attebury, Sprague, & Young, 2009; University of Idaho Library

The

University of Idaho Library created a “Research Assistance Program” (RAP) for

its patrons in 1998. Usage statistics compiled over 10 years were used to

determine if the service still effectively met the needs of its users. Using

quantitative and qualitative data, the authors examined consistencies in usage

patterns (i.e., male to female ratio, on-campus vs. remote users, undergraduate

vs. graduate students), average amount of time librarians spent preparing for

the individual consultation, the length of the consultation, how advanced in

the research process students were, types of assignments and sources, along

with challenges encountered (e.g., “no shows” and communication issues).

Students were required to fill out a form, either online or at the information

desk, requesting information on their topic, a description of their assignment,

the due date, and the number and types of sources required. Once the session

was completed, the librarian who met with the student completed a brief form

indicating how much time was spent preparing for the session, along with the

actual meeting time and follow-up (if any), how they communicated with the

student and any other problems that were encountered. The service was offered

to both undergraduate and graduate students, but the majority of students using

the service were undergraduate students. The authors concluded that the

service’s assessment process helped to better understand what direction to take

for the future of the service.

Becker, 1993; Northern

Illinois University (NIU)

The library

offered research clinics for a large-scale first year English program, with two

groups targeted: honour students and educationally disadvantaged students.

Librarians met with one or two students simultaneously, using their term papers

to introduce them to basic reference sources for locating books and articles

pertinent to their topic. It was noted that disadvantaged students appeared to

respond best to the sessions. While the honour students also benefited from the

sessions, authors noted that a different skill set were required for these

groups. Honour students had more sophisticated library research skills, so

their instruction needs were different than those of the educationally disadvantaged

students. Both the instructors and student feedback were given anecdotally.

While the librarians met and reviewed the program after the first semester of

implementation, the article provide a narrative evaluation of the program using

anecdotal feedback obtained from librarians and students, along with the

statistics acquired on attendance and hours. The author concluded that the

research clinics provided the needed follow-up to library labs already offered

to freshman students. It is also noted that staffing is the major challenge

identified in the pursuit of this particular service.

Hoskisson & Wentz, 2001; Utah State

University

A formal

program was created to address an increased need for individualized attention

for students needing assistance from a librarian at Utah State University.

Authors noted that demanding users complete a detailed information form may act

as a barrier to this service, so they avoided these forms and direct email

queries were used via web form. Unsolicited feedback from students came mostly

in the form of appreciation but also some mentioned they actually learned

library skills that they would reuse. Librarians provided anecdotal feedback,

indicating that if the “student did not respond with feedback, they could not gauge

how helpful they had been” (p. 99). While the article reported statistics

regarding the number of users per month, as well as librarian participation

(number of students met per month), no formal statistics were available

regarding the number of appointments versus email transactions per librarian.

In order to strengthen their students’ information literacy skills, the authors

mentioned that:

An accurate, formal evaluation system is

always difficult to implement. Perhaps a class will be taught and term paper

consultations set up with an equal number of students in order to make a

comparison of the two groups’ abilities to obtain pertinent research articles.

Pre- and post-tests would lend data with which to judge the value of the

program (p.100-101).

The authors

concluded that this new hybrid service exceeded their expectations since it

held a large number of queries, many positive comments from students.

Lee, 2004;

Mississippi State University Libraries

The

Mississippi State University Libraries provided individualized instructional

sessions to undergraduates, graduates, and faculty members. These sessions were

managed via an official service, where users must complete a form to request an

appointment. Librarians are expected to respond within 24 hours and to prepare

before the appointment (as per the institution’s reference department’s

performance standards). The form included information about referral source and

user’s department affiliation, which allowed the author to analyze one year of

usage statistics. The library was interested in the referral source in order to

evaluate their marketing strategy. Librarians (40.5%), faculty members (23%),

and outreach programs (16.2%) represent the most frequent referral methods. The

findings showed that users of the service were mostly graduate students

(64.9%), represented a variety of departments, with the department of education

being the most represented (32.4%). The author concluded that a different

promotion approach is needed for the undergraduate clientele, but the service’s

overall assessment is positive, since it provided extended research support to

its users.

Meyer, Forbes, & Bowers, 2010; Penrose

Library, University of Denver

Authors

described the implementation of a reinvented reference service divided in two

distinctive services: a research desk staffed with trained graduates students,

and a dedicated space with dual computers for one-on-one consultation, where

students can book an appointment with a subject-specialist librarian. The

service was inspired by the general design of writing centres, where students

can get help privately but yet in a visible open-space, which can ease

students’ anxiety when in need of help. Usage statistics show that both

undergraduate and graduate students were users of the service, as well as

faculty members. Social sciences and business students were the heaviest users

of the service. Anecdotal comments from users were recorded, which showed a

positive reaction to the new service. Librarians were also satisfied with this

new model, as it allowed them to better use their expertise rather than simply

staffing the reference desk. This unique model, with dual computers, allows

students to lead the interaction and to go at their own pace which helps

develop their research skills. The authors concluded “the consultation model is

more effective for student learning, more fulfilling for librarians, and more

efficient use of time for both” (p. 66).

Yi, 2003; California

State University San Marcos (CSUSM) Library

The author

described this article as case study of the CSUSM Library’s Individual Research

Consultation Service (IRCS). Eight advantages of IRCS over traditional

reference service are summarized. The author states that the IRCS provided a

channel for students to get in-depth individualized research assistance for

their projects with a subject information specialist. The IRCS was part of the

library reference service for several years, and it was offered to both

undergraduates and graduates. Students completed an individual appointment

form, where they indicated their research question and the nature of assistance

requested, then the student was matched with a subject librarian. The

librarians had to record the main topics covered on the appointment form, and

these forms were archived since 1996. The author analyzed two years of these

archived forms, coded the data and added it to a database. Direct observations

of IRCS, and interviews with three librarians, were additional methods used.

Usage statistics recorded the number of sessions, the hours provided, and the

number of students seen. The author also gathered the number of hours

librarians taught information literacy sessions, and determined that librarians

spent 32% of their teaching time, with IRCS being a type of teaching, doing

IRCS. Additional information extracted from the performed data analysis

indicated that 87% of IRCS sessions were course-project related, which, the

author emphasized, allowed for teachable moments as students had an immediate

need to be filled. Also, 31% of students had attended a library class previous

to requesting an IRCS, and 77% of these sessions were for students requesting

help for 300-level courses or above. The most frequent topics covered during an

IRCS were: “topic assistance”, “search skills”, “database selection”. The

author suggested that IRCS sessions have the potential to be a teaching medium

where information literacy goals could be better addressed if the librarians

involved are conscious of their role in that matter. The author concluded that

the IRCS could be developed as a multi-level, multi-phased IL program, instead

of an extension of the reference service.

Survey

Auster, E.,

Devakos, & Meikle, 1994; University of Toronto

The authors

outlined the planning, implementation, and assessment of a “Term Paper Clinic”

(TPC) for undergraduate students only. The TPC was the result of collaboration

between the Faculty of Library and Information Science and the Sigmund Samuel

Library, the main undergraduate library at the University of Toronto. MLS

students were the sole providers of individual consultations to undergraduate

students. The project was interesting for the library as it provided individual

consultations to undergraduate students as an extension of the existing

consultation service in place for graduate students and faculty members. MLS

students received a three-hour orientation (two hours in-class, and one hour in

the library). The TPC was scheduled for two-hour periods over three weeks

during the spring semester in 1993, where two MLS students were scheduled to

work each period. A designated desk near the reference desk was dedicated to

TPC, and the service was provided on a walk-in basis. The MLS student first

spent approximately twenty minutes with the undergraduate student and filled in

the TPC Library Research Guide Form to

record the needed information. The MLS student then created a tailored TPC Library Research Guide, and met with

the undergraduate student usually within twenty-four hours of the initial

meeting to provide the guide. To assess this new service, every undergraduate

student received a survey at the end of the second meeting, and asked to return

it to the reference desk. The survey had a 49% response rate. The service was

originally designed for first and second year students, but other academic

levels used the service as well, which showed that many students needed

individual in-depth assistance, and should not be denied that specific type of

service. Additional information extracted from the survey included: how

students learned about the service (77% from posters), their satisfaction level

(68% assessed the service as being very useful or somewhat useful), and what

skills were learned from the clinic (e.g. the need to focus, using different

research approaches, using keywords and subject headings). MLS students were

also asked to provide feedback on their experience. A content analysis of their

reports described the experience as a success and the MLS students commented

that they would like to see this service continued, they found it rewarding as

it provided them with practical experience. The overall analysis of the

experience also underlined some problems. Mainly, the MLS students’

inexperience was a barrier to provide an adequate service. Also, some

undergraduate students misunderstood the TPC’s goal and believed it would

provide essay-writing assistance. The author concluded that both the MLS

students and the librarians benefitted from this experience.

Bean, 1995; DePaul

University.

The author

describes the implementation and evaluation of DePaul’s research consultation

service, offered to both the undergraduate and graduate student population. The

implementation process included the creation of a “Research Consultation

Appointment Request Form”, and the development of procedures, such as length of

sessions to be provided. An evaluation process was put in place after the service

had been running for one year. Goals were set before the start of the

evaluation process. The method used was in two parts: 1) the librarian would

complete an evaluation form, then 2) the patron would fill out a separate

evaluation form. The response rate was of 91% for librarians, 55% for students.

Results from the librarians’ forms revealed that 86% of the time librarians

rated their sessions either “excellent” or “good”. Other information gathered

was “preparation time” and “sources used”. Students’ forms showed that 100% of

students surveyed rated sessions either “very helpful” or “helpful”. Other

information included the student’s program or department, and where they

learned about the service.

Cardwell, Furlong, & O'Keeffe, 2001; Gettysburg College, Marquette University, and Bowling Green State

University (BGSU)

The authors

analysed the personalized research clinics (PRCs) program offered at three

different institutions, and address logistics, assessment methods, and

publicity. At BGSU, PRCs are offered to undergraduate students. A similar

service is offered to graduate students and faculty members, but is managed

differently. PRCs are most utilized during a four-week period, but are also

offered throughout the semester. For that four-week period, a schedule is

organized with librarians’ availabilities. Students booked their appointment at

the reference desk and provided information about their research project.

Evaluation forms were given to students since the implementation of the

service. To strengthen the evaluation process, evaluation forms to be filled by

librarians were added to the mix, and paired with the student’s evaluation

forms. Data from this comparison exercise is not provided in the article. A

general comment is mentioned, where the authors state that after the

implementation of the two-part evaluation form, students’ comments were

“strong” (i.e., they were satisfied by the service).

The

Marquette University libraries provided PRCs to undergraduate students,

graduate students, and faculty members. Students booked appointments either on

the library website, by phone, or in-person. The requests were sent to either

the contact person for the humanities and social sciences, or for the sciences.

The contact person decided which subject librarian was the most appropriate for

each request. The librarian and the requestor then set up a meeting time. Usage

statistics were collected over the years including gender, affiliation,

academic level, and field of study. An eighteen-question survey was sent by

mail to all PRC attendees for one calendar year (2000). Twenty-five attendees

answered the survey, of which 70% were graduates students, and 30% were

undergraduate students. Results showed that 24 out of 25 respondents indicated

the session was “definitely” worth their time, while 22 indicated they would

“definitely” use the service again. The authors also stated that the service

seemed useful for students and seemed to meet their expectations. They

concluded that Marquette’s libraries would continue to provide the service.

The

Gettysburg College library underwent reorganization, thus readjusted how PRCs

were provided. Different assessment methods were used to evaluate the service.

Printed surveys were used. Details about this assessment are not available in

this article.

Coniglio, 1984; Iowa State University

The author described the staffing, scheduling,

publicity and evaluation of the “Term Paper Advisory Service” (TPAS) at the

Iowa State University Library. This service was designed for undergraduate

students, but graduate students and faculty members used the service as well. A

steering committee was formed to plan the TPAS’s structure. Fourteen librarians

offered the service, from which some were non-reference librarians. A training

session was held specifically for them before TPAS started. Their procedure

stated that there would be no effort to match student’s topic to a librarian’s

specialty, as the author pointed out, in order to mimic common reference desk

interactions. TPAS were scheduled for two two-week periods, around mid-terms

and finals. Students were requested to fill a worksheet asking information

about their topic. The appointment was then booked the next day, for fifteen

minutes. The librarian created a customized pathfinder before the appointment,

identifying relevant sources for the student. The meeting started at the

reference desk, and the librarian then took the student to the physical

location of the relevant sources listed. To assess the service, an open-ended

questionnaire was sent to the one hundred students who participated to the first

two-week period. Fifty-seven completed questionnaires were returned. The author

summarized the results, saying that students were very favorable to the TPAS

service. Students would recommend the service to a friend. After the service’s

revision, TPAS was to be offered all semester long, and four additional

librarians joined the team. Meeting length was also adjusted to thirty minutes,

and librarians’ preparation time was increased to 48 hours. The author

concludes “TPAS complements and supplements the basic work done with students

in library instruction classes and lectures” (Coniglio,

1984, p. 82).

Debreczeny, 1985; University of North Carolina

The author

describes the development of the “Term Paper Consultations” (TPC) at the

University of North Carolina’s Undergraduate Library. The TPC program did not

provide a bibliography to students, but rather a search strategy, along with

reference material. Students were also shown how to use the LC Subject Heading

Guide, and are shown potentially relevant periodical and newspaper indexes.

Students booked a thirty-minute appointment on a sign-up sheet, and each day

librarians selected appointments that worked with their schedule. The service

was offered year long, with busy periods of four weeks each semester. Four and

a half professional librarians, library school assistants, and one graduate

student staffed the TPC. With increased demands, the staff decided to record

the TPC appointments’ content on a form, which was designed to describe each

step of the research process. Eventually, an index of those TPC files was

produced, and was used both for TPC and for the reference desk. To assess the

service, a survey was conducted, which 60 students answered. Results show that

100% of respondents would have recommended the service to someone else, 90%

said they would have used TPC for another assignment, and 92% mentioned that it

fulfilled their expectations. The author pointed out that the TPC subject files

and the indexes developed over the years were extremely useful not only for the

TPC service, but also for everyday reference questions.

Gale and Evans, 2007; Missouri

State University

The Meyer

Library’s research consultation service was offered to all undergraduate and

graduate students, staff, and faculty. Requests were made through an electronic

form on the library website. These requests were routed to the appropriate

librarian according to subject expertise and availability. The form asked

specific questions about the student’s topic, resources already consulted, and

so forth, which allowed librarians to prepare before meeting the student. Two

surveys were designed to assess the research consultation service. The patron’s

survey, which consisted of both open-ended and Likert scale questions, was sent

to all of the service’s participants during one year. Results from 23 students

who answered the survey (31% response rate) showed that 52% of the respondents

strongly agreed that the library’s material selection met their research needs,

while 88% of respondents strongly agreed the consultation helped them with

their research. In addition, 60% of respondents strongly agreed they felt more

confident in their ability to use the library’s resources. The second survey,

consisting of six open-ended questions, was distributed to librarians providing

the service. The main results showed that all librarians spent at least 30

minutes preparing, and all respondents felt satisfied to have helped the

majority of the students. Librarians also commented that the service was

beneficial to the university community, and a valuable use of faculty time. The

authors concluded, in light of both surveys, that this kind of tailored

one-on-one service was worth continuing.

Gratch & York, 1991; Bowling

Green State University

The Bowling

Green State University (BGSU) Libraries were offering individual consultations

to all students for many years. These consultations were not specifically

tailored to graduate students’ needs, and were not highly publicized. A pilot

project, the Personalized Research Consultation Service (PERCS), provided

individual consultation to graduate students specifically. Four departments

were included in the pilot project, and 30 students used the PERCS in the first

year. A survey was sent to the participating students. Additionally, phone

interviews were carried out with faculty advisors to ask their opinion of the

service. The survey produced a 56.7% response rate. Results show that all

respondents found the consultation helpful, and they would recommend the

service to a friend, and 76.5% of the respondents used PERCS to get help with a

thesis or dissertation. Once the pilot project was over, it was decided to

continue the PERCS and to make it available to all graduate students.

Imamoto, 2006; University of Colorado

The Boulder

library at the University of Colorado embarked on a partnership with the

University’s Program for Writing and Rhetoric (PWR) to integrate information

literacy concepts in the first-year course, which consisted of four parts: 1)

online tutorial on basic library research, 2) course-integrated library

seminar, 3) theme-based course reader, and 4) drop-in “Research Center”. The

Research Center is different from the library’s usual individual consultation

services because no appointments are needed, only graduate students staff the

Center, and it is available only to undergraduate students registered in a

specific writing course. The graduate students are provided with a

comprehensive training at the beginning of the school year. To assess the

Research Center, an evaluation form with three open-ended questions was given

to each student at the end of the interaction. Two questions were added the

following semester. Completed forms were to be dropped off at the Research

Center. In total 95 students filled out the evaluation form, for a response

rate of 23%. Results show that 95% of respondents felt the graduate student

providing the consultation was helpful, 15 respondents requested more hours as

an area of improvement, and 6 respondents asked for more tutors (graduate

students). Students’ experience of the Research Center scored 4 or 5 out of 5

for 83% of respondents. In conclusion, the author articulates additional

information that would be helpful to gather in a future survey, such as

students’ backgrounds, which could help understand better what students need in

order to improve the service.

Magi & Mardeusz, 2013; University of Vermont

This study

used a qualitative approach to investigate students’ views on individual

research consultation value, and what motivates students to request this

particular type of assistance. Both undergraduate and graduate students

requesting research help were included in the study. Moments after the

consultation was completed, students were invited to answer an open-ended question

survey. The authors expressed how this study is not about the “effectiveness of

consultations in terms of student learning outcomes” (p. 608), but rather why individual research consultations are valuable to

students. In total 52 students responded to the survey. Results show that

students learned about the research individual consultation service mostly

through professors, and from in-class library presentations. All respondents said they would use this service

again. More than

one-third of respondents said that their motivation for booking a consultation

“was the need for help finding information and choosing and using resources”

(p. 610). When the students were asked about the type

of assistance that the librarians provided during research consultation,

three-quarters of respondents answered: “by selecting and recommending sources,

including databases and reference books, and brainstorming about places to

search” (p. 611). The authors also asked:

What do students who use individual

consultations find valuable about face-to-face interaction with librarians,

even with the availability of online help? The authors summarized results

in this way: “a face-to-face interaction allows for clear, quick, efficient,

and helpful dialogue; can ask questions and get immediate responses” (p. 612).

Students also mentioned how a face-to-face meeting allows for a replication of

the steps taken by the librarians in the resources navigation. Lastly, the

authors asked the students to describe their feelings before and after the

consultation. Before the appointment, one-third of the respondents used the

words “overwhelmed”, “stressed” and “concerned”. “Relieved” is the word most

frequently used by students to describe their feeling after the consultation,

and “confident” and “excited” were also popular expressions. The authors

concluded that reference librarians, who care deeply about students’

information literacy competency development, should consider making individual

research consultation part of their reference service.

Rothstein, 1990; University

of British Columbia

This

article is a reproduction of a presentation the author offered in 1979 about a

“Term Paper Clinic” (TPC) conducted at the UBC Sedgewick Library for a number

of years, with MLS students staffing the Clinic. The TPC was offered twice a

year for a two-week period to undergraduate students only. MLS students had a

five-week preparation period that comprised of instructions in reference

sources and strategies, a lecture by the professor, an accompanying written

guide called The TCP Literature Search:

Approaches and Sources, a library tour, in-class sample question practices,

and access to TCP guides previously produced. During the TPC’s operation

period, students (called “recipients” by the author) would meet twice with the

MLS student; they would first register and provide information about their

needs, then a second meeting would be scheduled to provide the recipient with

the desired information in form of a search

guide. To assess the TCP’s success, three feedback methods were used.

First, the MLS students submitted a report on their experience. Second, the

Sedgewick librarians’ anecdotal comments were captured. Third, recipients were

asked to fill out a questionnaire. MLS students’ comments were summarized as

followed: “TPC gave them a sense of confidence as they realized that they did

indeed have a great deal of knowledge which laymen did not possess; they began

to think of themselves as professionals” (p. 263). One downside of this project

for MLS students was time, as it was more work than anticipated for them to

produce the search guides. Sedgewick librarians, on the other hand, had almost

all favourable comments for the TPC. Recipients’ feedback was taken through a

questionnaire that was sent out to all TPC’s participants every semester. The

author analyzed the results of one particular semester (fall of 1976). The

evaluation form held a 30% response rate (77 students). Main results showed

that 90% of respondents answered that the service provided was either extremely

or very useful, that 94% of respondents said that the TPC helped them improve

their knowledge of library resources, and that 92% of respondents mentioned

that they feel better prepared to use the library on their own. As an

additional evaluation, in 1976 an MLS student conducted 60 interviews with

recipients of the service. Her findings support the results obtained by the

recipients’ evaluation forms, MLS students’, and librarians’ feedback. The

author concludes that a “personalized, extensive reference service provided at

the point of need is a very effective method of teaching the use of the

library” (p. 269).

Schobert, 1982; University

of Ottawa

The author

describes the planning, execution, and evaluation of a pilot project held at

the University of Ottawa’s Morisset Library called

“Term Paper Counselling” (TPC). The TPC was held once during the academic year,

for a two-week period in the winter semester, and was to be provided only to

undergraduate students. Students had to first book an appointment and fill out

a form providing information about their topic. Librarians would then prepare a

search guide that provided a selection of indexes, bibliographies, etc. During

the appointment, the librarian would go through the guide showing the student

how to use the various suggested bibliographies and indexes. To evaluate this

new program, the author sent a questionnaire to all participants one month

after the TPC was over. Only 19, students answered, though almost all

respondents were enthusiastic about the new service. The author concluded that

TPC is a worthwhile service, and will continue providing it.

Objective

Quantitative Methods

Erickson &

Warner, 1998; Thomas Jefferson University

The authors

conducted a one-of-a-kind study, where the impact of a one-hour MEDLINE

individual tutorial was assessed with specific outcomes measured (i.e., search

frequency, duration, recall, precision, and students’ satisfaction level).

These individual sessions were specifically designed for obstetrics and

gynaecology residents. This was a randomized, controlled, blinded study,

conducted with 31 residents. These students were divided in three groups. Group

A was the control group that received no formal MEDLINE tutorial. Group B and

Group C received one-hour individual tutorials, including advanced MEDLINE

search features, such as MeSH searching, focus and

explode functions, and so forth. Group B had their tutorial in a hands-on

format, where the residents performed the search themselves. Group C received a

tutorial where the instructor performed the searches. All participants answered

a survey before and after their searches, asking them about their computer

experience, what they thought was a reasonable number of articles retrieved

when searching MEDLINE, and how long a search should take. No statistically

significance differences were detected among participants. All residents had to

perform four assigned searches; two before the tutorial, and two after. Three

faculty members independently rated the citations retrieved for relevance. A

seven-point relevance scale was developed for this purpose at McMaster

University (Haynes et

al., 1990). The

primary investigator rated recall and precision. Results show that there were

no statistically significant differences between the pre-tutorial assigned

searches and the after-tutorial assigned searches for the search duration, the

number of articles retrieved, the recall rates, the precision rates, or the

searcher’s satisfaction level. Limits to the study included the small group of

participants, low compliance rates, and a change in the database platform at

the study’s mid-point. Participants felt satisfied with their searches both

assigned (85%) and unassigned (64%), and were interested in improving their

MEDLINE search skills (60% wanted further formal training). The authors

concluded that time constraints is a major obstacle for information

professionals to provide individual tutorials, especially since there were 700

residents and fellows at this institution that particular year, and for

residents who struggle to free some time from their busy hospital schedule to

receive adequate database search skills training.

Donegan, Domas, &

Deosdade, 1989; San Antonio

College

Authors describe a bibliographic instruction experiment comparing two

instructional methods: group instruction sessions vs, individual instruction

sessions called “Term Paper Counselling” (TPC). Participants included 156

students enrolled in an introductory management. The authors first developed

learning objectives that would be used to measure students information literacy

skills for both instructional methods. Then, they created and tested two

versions of multiple choices questions, which they trialed with two groups of

students (one having had library instruction, and the other did not). Data from

the testing was compiled, and no difference appeared between the two versions.

However, a difference was noted between the two groups regarding the students’

IL knowledge, which was expected since one group had not received a library

instruction course yet. In the fall semester, students from the management

course were divided in three groups. Group 1 received group instruction, Group

2 received TPC, and Group 3 received no instruction as the control group. All

students were informed that a library skills test would be administered and it

would be worth 5% of their grade. For Group 1, the test was administered right

after the library instruction. For Group 2, librarians had to prepare a

pathfinder first on each student’s topic, followed by a meeting with the

student (individually), then students would be given 25 minutes (same length of

time for all groups) at the end of the meeting to answer the test. Group 3 was

given the test in the classroom. Once their test was completed, the librarian

would inform them that they were part of an experiment, and they would be

allowed to retake the test after they were provided with a library instruction

session. Using Tukey’s HSD (Honestly Significant Difference) Test, results show

that a significant difference existed between TPC and the control group, as

well as between group instruction and the control group; but no significant difference

was found between TPC sessions and group instruction sessions. The authors

conclude that “Term Paper Counselling and group instruction are comparably

effective techniques for teaching basic library search strategy” (p.

201).

Reinsfelder, 2012; Penn State Mont Alto

This author used citation analysis to evaluate the quality of students’

sources included in draft papers before meeting a librarian, and again with the

final paper after the meeting with a librarian. Criteria used were currency,

authority, relevance and scope. Faculty members teaching various undergraduate

courses were invited to participate in the study by inviting their students to

book an appointment with a librarian, and by sharing their students’ drafts and

final papers for citation analysis. In total 10 classes were included in the

study, 3 of which were part of the control group, where students’ draft and

final papers would be assessed, but students would not meet with a librarian.

Additionally, faculty members were asked three open-ended questions to provide

their observation and perception of the process. Nonparametric statistical

tests were used for data analysis. For the experimental group, those who met

with a librarian), a significant difference between draft and final papers was

found in all criteria except for authority. No significant difference was found

for the control group. Faculty commented that this approach was worthwhile. The

author indicated that using a rating scale is useful to measure objectively

students’ sources’ quality, but there is room for subjective interpretation.

The author concluded that students who partook in an individual research

consultation with a librarian showed an improvement in their sources’ quality,

relevance, currency and scope.

![]() 2015 Fournier and Sikora. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Fournier and Sikora. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.