Introduction

At

our polytechnic institution, librarians are often called upon to teach learners

from a variety of programs, from trades to health sciences, to business and

technology programs. Like the majority of teaching faculty at the institution,

librarians do not have a diploma or degree in adult education. In an attempt to

address this education deficiency, our institution requires instructors in all

programs and services, including library services, complete the Faculty

Certification Program (FCP), an adult education teaching certificate, in order

to retain their positions. The courses required to complete the certificate

include adult learning theories, instructional strategies, adult development,

technology in teaching, curriculum design, evaluation of learning, and

leadership. FCP is designed to provide

new instructors with the basic knowledge and skills needed to teach adult

learners. The challenge that our

polytechnic librarians have, that other teaching faculty do not, is that we

often teach single sessions to students in a variety of programs. This means

librarians lack the opportunity to get to know students’ strengths, challenges,

and learning preferences over time. Our participation in the FCP program

prompted us to ask the question: would applying a learning theory to an

information literacy workshop increase student engagement, given that

librarians often teach single sessions to a variety of student groups?

In

the fall of 2014, as liaison librarians for a baccalaureate nursing program, we

(the authors of this article) were asked to provide four three-hour workshops

on database searching and American Psychological Association (APA) writing

style to 150 first-year nursing students. Previously, we had both taught the

workshop independently of one another but the students who met with us to ask

follow-up questions indicated inconsistencies in their understanding resulting

from two different instructors teaching the workshops. So we embarked on this

project in order to bridge this gap and to apply what we learned in FCP to our

instructional practice. Our two main objectives were: 1) to improve student

engagement with information literacy skills instruction and, 2) to grow as

professionals by perfecting our teaching skills. This paper describes the

process of applying Kolb’s learning theory to practice and our reflection of

that process towards achieving student engagement and becoming better

instructors.

We

chose Kolb’s theory because it postulates that experience is a critical aspect

of the learning process, which aligns well with library instruction as it often

involves hands-on experience in order to make sense of learning (Kolb, 2014).

According to Kolb’s theory (2014), teaching to various learning styles and

facilitating the learner’s progression through the learning cycle is necessary

in order to create new knowledge. Because this theory highlights the importance

of experimentation, reflection, and abstract conceptualization, it is suited to

information literacy instruction; research skills and information literacy are

more than just imitating keystrokes, they require creativity and critical

thinking.

Literature

Review

A literature search was conducted to

find publications on the topic of how to incorporate Kolb’s learning theory in

library instruction. Although librarians are applying learning theory to

instructional practice, using approaches such as Tiered Instructional Programs

(Bowles-Terry, 2012), Adult Learning Theory (Lange, Canuel, & Fitzgibbons,

2011) and Evaluation Methodologies (Schilling & Applegate, 2012), we were

unable to find any specific examples of the application of Kolb’s theory. Woods (2012) provides a list of suggestions on how to

consult Kolb’s cycle of learning when planning information literacy sessions by

emphasizing the use of a variety of teaching strategies to meet the preferences

of all learners. Other than Woods’ suggestions for how to incorporate

Kolb’s theory

we were unable to find literature on librarians actually applying Kolb’s

theory to their instruction. One reason for this may be that as librarians

generally conduct one-shot information literacy sessions in a wide array of

programs, the varying subject matter and timeframes make the application of

Kolb’s theory difficult. Other teaching

faculty see students daily or weekly and therefore have the ability to get to

know the students over time. These faculty have time to build on

previously-taught concepts, assess learning, and adjust their teaching

strategies and materials as needed, making it easier to apply adult learning

theory to instruction.

While little research exists on

using Kolb’s theory to guide library instruction, its use in the fields of

adult education, business, social work, and nursing has been well documented.

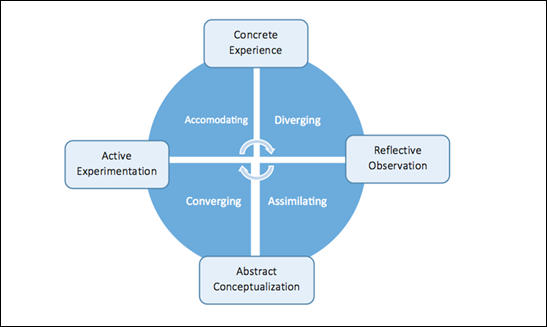

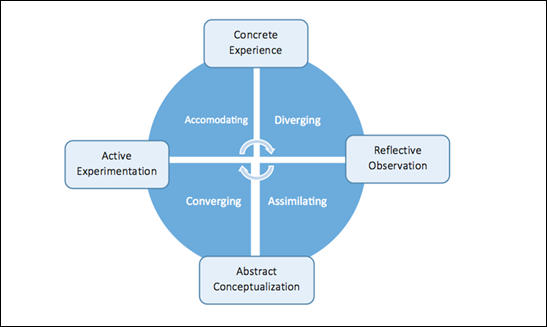

Kolb’s learning theory includes learning styles and his cycle of learning

(Figure 1). Since its conception in 1984, academics and practitioners in the

field of education have analyzed and implemented Kolb’s theory into their

practice. Even today, Kolb continues to inform instructional design

(Bergsteiner, Avery, & Neumann, 2010; Lisko & O’Dell, 2010; D’Amore,

James, & Mitchell, 2012; Cox, Clutter, Sergakis, & Harris, 2013).

Figure

1

Kolb’s

Experiential Learning Theory. Adapted from Experiential

learning: Experience as the source of learning and development, by D. A.

Kolb, 2014, Upper Saddle River: Pearson. Copyright 2014.

According

to Kolb & Kolb (2005), there are four types of learning styles that

instructors may encounter in every classroom:

·

Diverging

style learners are able to view experiences from multiple perspectives, are

creative, open minded, interested in people, imaginative, emotional, open to

feedback, are able to gather information, have broad interests, and enjoy group

work. These learners enjoy concrete experiences and reflective activities.

·

Assimilating

style learners are logical and are able to understand a wide range of

information. They are less interested in people and are more interested in

ideas, concepts, and theory. These learners may prefer lectures, reading,

exploring models, and having time for abstract conceptualization and

reflection.

·

Converging

style learners can put theory into practice and solve problems. These learners

may prefer technical tasks and problem solving to social or interpersonal

experiences. They learn best through abstract conceptualization and active

experimentation.

·

Accommodating

style learners learn from active experimentation and concrete experiences.

These learners rely on others for information and group work to achieve their

goals (Kolb & Kolb, 2005, pp.196-197).

For

learning and knowledge creation to occur, Kolb & Kolb (2005) contend that

instructors must create a learning space that is welcoming and respectful of

past experiences while meeting the learner’s current needs. They must also

provide a space for conversational learning, experimenting and reflecting,

which encourages intrinsic motivation and allows learners to take charge of

their own learning. In Kolb’s learning cycle, learners move through: (1)

concrete experiences, using past and present experiential learning to inform

new learning; (2) reflective observation, which leads to (3) abstract

conceptualization, which is followed by (4) active experimentation (Kolb,

2014). New knowledge is only created through active experimentation and

reflection (Lisko & O’Dell, 2010).

Determining

which learning style is characteristic of students in a particular discipline

is difficult. D’Amore et al. (2012) explored the learning styles of first-year

undergraduate nursing and midwifery students at an Australian university, and

found that the majority of the students surveyed were “divergers” (p. 507).

Although they were able to identify a dominant learning style, the authors

conceded that as people move through various stages of growth and development,

they become capable of drawing from all four learning styles. D’Amore et al. (2012) therefore concluded

that students should “not rely solely on one style” (p. 514). Cox et al. (2013) identified the learning

styles of senior students in four undergraduate health programs and found a

variety of learning styles in both the classroom and clinical setting and that

no predominant learning style emerged. The evidence therefore indicates that it

is important for educators to use a variety of teaching strategies in order to

engage learners with different learning preferences. Accordingly, creating a

lesson plan that piques the interest of all four learning styles is more

important than identifying what type of learner a student might be.

There

is a connection between the skills built through experiential learning and the

skills required to become information literate. In their study, Devasagayam,

Johns-Masten, and McCollum (2012) found that requiring students to participate

in experiential exercises that require application to reinforce learning and

are strengthened through repetition, is an effective way to teach information

literacy because it encourages critical thinking via problem solving. Clem,

Mennicke, and Beasley (2014) describe experiential learning as something

involving an experience that engages the physical body “in an effort to

holistically enhance the process of learning” (p. 491). They have found that

students learn better when the teaching approach is student-centered, when

students can take control over their learning, and when the lesson is relevant

to them. Lisko and O’Dell (2010) believe that active experimentation and

reflection are essential to transform learning into knowledge creation.

From the current literature on

Kolb’s theory being applied to nursing instruction, it can be summarized that

nursing students have a variety of learning styles, that their styles can

change over time and according to the learning environment (whether classroom

or clinical), and that nursing students prefer a variety of experiential

learning strategies. Halcomb and Peters (2009) changed the curriculum for an

undergraduate nursing course to incorporate more reflective and active

learning. They surveyed their students at the end of the course and found that

there was a positive response to the variety of interactive teaching strategies

introduced (Halcomb & Peters, 2009). Lisko and O’Dell (2010) changed a

medical-surgical nursing curriculum to meet the varied learning styles of their

students by incorporating more scenario and experiential based teaching.

Overall, their student and faculty feedback was positive and the authors felt

that their methods enabled the “development of nursing students’ critical

thinking abilities” (Lisko and O’Dell, p. 108). Crookes, Crookes, and Walsh

(2013) found that nursing students preferred various experiential and

reflective teaching techniques: technology tools, simulations, gaming,

art, problem-based learning, and narrative activities for reflection and for

linking theory to practice. Based on

a review of the literature, the application of Kolb’s theory is well-suited to

the nursing classroom.

Methods

This study answered the following

questions: Does using Kolb’s theory in library instruction enhance student

engagement and does it improve teaching practice? Four forms of

qualitative feedback were collected to determine how Kolb’s theory contributed

to the students’ engagement and how it improved our instruction: (1) we

assessed the learning experience using a student post-class qualitative

feedback form; (2) we reflected on our teaching; (3) we provided feedback to

each other after observing one another teach, and; (4) an instructional

facilitator, whose job description is to guide and support the growth of

instructional faculty, observed and provided feedback to us on our teaching

skills.

Student Feedback

The

student post-class qualitative feedback form asked students to respond to the

following questions:

1.

How

did you feel about your [research and APA skills] before the session?

2.

How

did you feel about your [research and APA skills] after the session?

3.

What

do you attribute the cause of the change in how you feel if there was a change?

4.

What

was the most impactful thing you learned?

5.

What

teaching activity was least useful and why?

The

feedback provided us with guidance and resulted in changes to the lesson plans

as well as modifications to our teaching strategies.

Librarian Reflection and Peer Feedback

In

an effort to reflect and share our teaching experiences, we met to debrief at

the end of each lesson. We discussed the following questions:

1.

How

did you feel about your teaching experience?

2.

What

were the students’ reactions to your teaching strategies?

3.

What

changes to the content or teaching strategies would you make to improve student

engagement?

These

questions encouraged us to reflect, to gain insight, and to become aware of the

impact of our teaching practices on the learners. In the debriefing sessions

after implementing the revised, second lesson plan from which we team-taught,

we provided verbal feedback regarding one another’s performance. This feedback

led to further reflection and discussion.

Faculty Facilitator Feedback

The

faculty facilitator’s knowledge, experience and expertise in guiding the

professional development of instructors provided us with further insight into

best teaching practices. She observed our teaching, made notes, and provided

verbal feedback to us after each teaching session. Her suggestions led to

further discussion and changes to our lesson plan and teaching strategies.

All four forms of qualitative

feedback were transcribed in a Microsoft Word document, which we used to change

our lesson plans, and to track our progress as teachers. Our first

attempt at incorporating Kolb’s theory into our teaching practice was delivered

to the first group of nursing students (Lesson One). Then, after processing

feedback, a second lesson plan (Lesson Two) was created to more effectively

incorporate Kolb’s theory.

Lesson One: First Attempt at Incorporating Kolb’s

Theory

We

met to create one common lesson plan: learning goals, learning content,

teaching materials, and teaching activities. For this lesson, we incorporated

Kolb’s theory based on our interpretation. We chose our teaching strategies

based on our teaching experience and our learning styles. Our teaching

strategies included asking pre-assessment questions about past experiences, a

lecture, and a demonstration followed by individual activities. We stayed at

the front of the room and came to the students who asked for help. Our

discussion questions focused on their understanding of what was lectured on or

what was demonstrated. A post-assessment form was used to assess students’

experience and the instructors debriefed afterwards to discuss our teaching

experience and our observation of students’ engagement.

We

asked the faculty facilitator to observe our teaching sessions and give us

feedback on our instructional methods. She observed that we had not

incorporated Kolb’s theory into our lesson plan effectively. She commented that

although our lesson plan had elements of Kolb’s theory, such as reflective and

experiential activities, we were not teaching to all learning styles, nor did

we facilitate moving the students through the learning cycle. She felt that our lesson plan was more

traditional than experiential. Using her suggestions, our reflection of our

practice, our feedback to each other, and the students’ feedback, we created a

new lesson plan that incorporated more experiential learning and reflection as

suggested by Kolb’s theory.

Lesson Two: Effective Incorporation of Kolb’s Theory

Kolb’s

theory was incorporated into our teaching material, activities and strategies

in the following ways:

·

We

taught this workshop as a team in order to learn from each other through

reflective observation and discussion.

·

We

facilitated the class activity, discussion and learning instead of lecturing from

the front of the room. We engaged all learners by walking around the room as we

talked and asked reflective questions of learners sitting at the front, middle

and back of the classroom.

·

We

facilitated a discussion on their past concrete experiences with research and

APA style, giving them time to reflect before beginning questioning.

·

We

facilitated discussions and provided time for a dialogue of student

observations, ideas, and opinions on their new learning.

·

Through

a learning activity on database searching, we encouraged students to search

using their usual methods and then to try a new approach to research before

coming to a conclusion. We encouraged them to use their past experiences, and

to observe and reflect, as well as actively experiment with new approaches to

search.

·

To

teach APA style, we used paired learning activities for peer-to-peer support

and peer-to-peer learning, and we encouraged them to independently search for

answers using a variety of resources.

Understanding

that we needed to facilitate their movement through the Kolb’s cycle of

learning, we used a variety of teaching strategies designed to appeal to

different learning styles:

·

For

assimilating style learners, the lecture combined with discussion questions

encouraged reflective observations.

·

For

assimilating and diverging styles, a video and a demonstration, as well as

classroom discussion and a reflective post-class survey, encouraged the sharing

of reflections and observations.

·

For

diverging and accommodating styles, paired activities allowed for active

experimentation and concrete experiences.

·

For

assimilating and converging styles, individual activities allowed for active

experimentation and concrete experiences.

Additionally,

the emphasis on reflective sharing and paired activities required that the

students remain focused and accountable.

Results and

Discussion

Students’ Reflection and Feedback

We

wanted to know if the students in Lesson One, where we first attempted to

incorporate Kolb’s theory, had different experiences from the students in

Lesson Two, where we more effectively incorporated Kolb’s theory after student

feedback and our own reflection. Students completed a post class survey meant

to facilitate reflection. From this survey we were able to gather some general

conclusions about their experiences. There were no remarkable changes in the

student feedback from Lesson One to Lesson Two. The majority of students in

both sessions responded that: (1) they felt a positive change in their level of

confidence after our teaching sessions; (2) they attributed the change to what

they learned in the session; and (3) they found the session to be valuable and

useful, with a few students finding the content to be confusing at times. Some

suggestions for changes from both student groups included: increase the length

of the session, decrease the length of the session, incorporate a break, and

slow the pace of the lesson. These results may indicate that different students

had different needs and that different aspects of our teaching appealed to each

type of learner in each session regardless of teaching Kolb-style or not.

The

student survey was not designed to evaluate our teaching effectiveness. It was

meant to encourage student reflection on their learning experience as reflective

observation is a key component of Kolb’s theory (Kolb, 2014). This activity

allowed learners to reflect on what they had learned, what they did not

understand, and prompted them to take control of their learning by seeking

answers or librarian support.

Both

librarians and the instructional facilitator perceived a change in student

engagement between Lessons One and Two. We collectively observed the students

to be more engaged when Kolb’s theory was more effectively incorporated into

the lesson. The students appeared more focused on their learning activities,

and more involved in the paired and classroom discussions and group work, and

there was more time allotted for reflection and active experimentation. We

perceived them to be less distracted and more actively involved in all aspects

of learning.

Facilitating Students’ Movement Through Kolb’s Cycle

of Learning

Kolb’s

theory is about facilitating learning by moving learners through each stage of the

learning cycle so that they may be able to understand and transform their

learning into new knowledge (Kolb, 2014). Knowledge creation is facilitated if

learners are able to resolve the cognitive dissonance between their previous

learning experience with new learning, between concrete experience and abstract

conceptualization as well as between reflective observation and active

experimentation (Kolb, 2014). The following section provides an example of how

we facilitated students’ movement through the learning cycle in the database

searching portion of the class.

Concrete

Experience

At

this stage, learners rely on their concrete experiences as they approach a

task, using knowledge and skills based on both past and present experiential

learning. We gave the students time to demonstrate their current searching

skills on a research question related to their course assignment. Most students

used internet search engines, some used Google Scholar, and a few used

databases. Although some were successful at finding journal articles, none

searched in a systematic manner.

Reflective

Observation

Reflective

observation is about critically analyzing the learning and considering the

impact of what has been learned. First, we facilitated a reflective

conversation in which they shared their approaches to finding journal articles.

We taught the students how to systematically search by introducing them to the

following skills: creating a search strategy, using subject terms and keywords,

choosing the appropriate databases, using limiters, and applying the same

search strategy across various databases. To encourage reflective observation,

we provided time to conduct searches using both the new method they had just

learned and their previous methods. The students compared their results, and

then shared their findings with a peer, then the class. This provided another

concrete experience on systematic searching and facilitated another reflective

discussion on their new experience.

Abstract

Conceptualization

At

this stage, learners critically analyze the new skills and think about how it

applies to them accomplishing a task. In order to facilitate this internal,

personal, and individualized cognitive process, we asked the students to work

with a peer to create a new a search strategy in order to find peer reviewed

journal articles for their research question. This activity encouraged them to

collaboratively work through a problem and think critically about their past

and new learning experiences in order to create an individualized approach to

systematic searching. It was our hope that they would synthesize their original

method with ours to complete this search.

Active

Experimentation

At

this stage, learners experiment with what they have learned and adapt it to

their individual style in order to accomplish a task. We encouraged the

students to adapt what we taught them and merge it with any previously

successful searching strategies as they attempted to apply the new skills to

their new search. We acknowledged there are different ways to search

systematically and we encouraged students to experiment in order to find what

will work best for them in the future.

Librarian Experience: Reflection and Feedback

The

general themes that arose from our reflection and feedback sessions with each

other and with the faculty facilitator are highlighted in Table 1.

Our

reflective practice, inspired by applying Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory

to library instruction, has been essential to our growth and development as

adult educators. Self-reflection and soliciting feedback from multiple sources

encouraged insight and awareness of the effects of our teaching styles. Through

this process we learned the value of making time to debrief with each other in

order to facilitate our instructional development. We learned to value our

differences while challenging ourselves to try new strategies in an effort to

improve student engagement with information literacy skills.

Table

1

Self

Reflection and Feedback Session

|

|

Self-Reflection

|

Peer Feedback

|

Faculty Facilitator Feedback

|

|

Lesson One

|

On our teaching:

· Well organized

· Good time management

· Lesson was relevant and applicable to

students – the lesson aligned with a research assignment the students were

expected to complete for their nursing course

· Overall, satisfied with lesson plan and

teaching strategies

On student

engagement:

· The students were focused on learning

activities.

· Most students participated in activities.

|

We discussed:

· the pros and cons of our different communication

styles, as they had an effect on our delivery of the lesson plan.

· the pros and cons of the content we

emphasized during the session (e.g., APA references vs. APA citations might

receive more emphasis depending on the teacher).

|

On our teaching:

· Teaching styles did not appeal to all types

of learners.

· We stood at the front of the room and

lectured.

· Our questioning did not encourage reflection

and critical thinking from the students.

On student

engagement:

· Low engagement. Many students were not

engaged in learning, but were searching other websites.

|

|

Lesson Two

|

On our teaching:

· Initially, we were reluctant to try new

teaching strategies.

· We felt a time pressure in modifying the

lesson by applying Kolb’s theory.

· Over time we felt we had expanded our

knowledge with the new teaching strategies.

· We felt empowered by the new strategies.

· We perceived the lesson to have been a

success.

· The lesson was relevant because it was tied

to a course assignment.

On student engagement:

· Greater student discussion, collaboration

and focus on their learning activities

|

We discussed

· Recognition of our different teaching

styles.

· Appreciation for one another’s strengths as

teachers.

We noted:

· We had become more learner-centered and less

teacher-centered. We would ask ourselves questions like what is the impact of

our actions on the learners? We focused less on how we liked to teach and how

we liked learn.

· We had become facilitators of learning instead

of lecturers.

· We learned how to effectively give and

receive feedback.

|

On our teaching:

· A variety of teaching styles were used to

meet the needs of various learners.

· We moved around the classroom engaging

learners from all corners.

· The activities were more reflective,

stimulating critical thinking.

On student

engagement:

· High engagement. All students participated

in the activities rather than visiting other websites.

|

Librarian Experience: Kolb’s Cycle of Learning

For

our professional development, we used Kolb’s theory to process what we had

learned about library instruction when we used his theory to guide teaching

practice. We reflected on our learning style and teaching strategies as we

progressed through Kolb’s cycle of learning in order to gain insight into our

teaching practice. The following section outlines our movement, as instructors,

through Kolb’s cycle of learning.

Concrete

Experimentation

In

Lesson One, we created content, teaching activities, and teaching strategies

based on our past learning and teaching experiences and preferences. Student

feedback was generally positive and our perception of the lesson was that it

was organized and well managed. The students appeared engaged in the learning

activities as they all completed the assigned tasks. We later realized that we

were looking for strengths in our practice that validated our bias that we were

effective instructors. The objective feedback from the instructional

facilitator, an experienced instructor of adult education who observed our

teaching, provided us with information that challenged our thinking and our

practice.

The

instructional facilitator’s feedback on Lesson One, our first attempt at

incorporating Kolb’s theory, was as follows:

·

During

the lecture some students were engaging in their own conversation or using the

computer for other purposes.

·

The

students appeared bored and distracted at times, especially those students

sitting at the back of the room.

·

We

stood at the front of the room and mostly engaged with learners at the front.

We did not engage learners from all areas of the classroom.

·

We

asked closed ended questions about comprehension but did not wait for

responses.

·

We

did not ensure student accountability for their learning activity, nor did we

evaluate their search queries or their APA exercise.

The

instructional facilitator recommended the following changes be made in order to

more effectively incorporate Kolb’s experiential theory:

·

When

lecturing, walk around the room to get the attention of learners from all

corners of the classroom.

·

Have

paired activities for peer-to-peer learning and support as well as individual

activities for those learners who prefer to work on their own.

·

Encourage

discussion and reflection by asking reflective questions and giving students

time to answer.

·

Ensure

students are engaged by randomly asking reflective questions to students in all

corners of the classroom.

·

Ensure

students are accountable for their learning by asking them to show you how they

search or how they apply APA.

·

Give

students time to experiment and compare their past search practices with the

new approaches that have been introduced.

Reflective observation

Transforming the

lesson

We

compared the feedback from the instructional facilitator to our observations of

the students with our first attempt at incorporating Kolb’s theory. From our

point of view, the students appeared engaged and we questioned the need for

change. We were reluctant to incorporate the changes due to time constraints.

Creating an experiential lesson plan would require the addition of new

activities for reflection, abstract conceptualization, and active

experimentation. All of these additions are time-consuming and we questioned

the feasibility of incorporating Kolb’s theory into practice. Ultimately, we

decided to experiment with the suggestions and assess the student’s engagement

when Kolb’s theory was applied properly.

Our Learning

Styles

Another

insight we had was: as teachers, our learning styles affect our teaching

styles. In our previous experiences of teaching this class, we focused on

content, teaching activities, and teaching strategies that were based on what

we valued, our past experiences as learners and instructors, our learning style

preferences, and what we learned in our Master’s of Library and Information

Studies and FCP. Completing Kolb’s learning style inventory revealed that one

of us favors a converging learning style, while the other is a combination diverging

and assimilating style learner. Converging style learners tend to have a

natural instruction style, which focuses on the practical application of

searching skills which can be applied to the student’s assignment, whereas the

assimilating/diverging learner favors reflecting in a structured way through

organized activities such as lectures, readings and discussions in order to

explore new ideas and skills (Kolb, 2007). Teaching strategies such as

brainstorming sessions and using guided logical conversations to find solutions

to problems may appeal to assimilating/diverging learners.

These

differences in our learning styles as instructors became evident throughout the

project. At the completion of each lesson, we would often view different

learning activities as having been the “most impactful” in cultivating student

engagement and we would often disagree on strategies for moving forward. Upon

reflection, we found strengths in these differences that resulted in teaching

approaches neither of us had considered before.

We came to realize, as Kolb states, “ideas are not fixed and immutable

elements of thought but are formed and reformed through experience” (Kolb,

2014, p. 36).

Abstract conceptualization

Using

Kolb’s theory in library instruction presented some challenges in terms of the

time required to move students through the learning cycle. To add to this, we

understood some of the criticisms of Kolb’s learning style and cycle of

learning. Coffield, Moseley, Hall, and Ecclestone (2004) did a systematic

review of various learning styles models with the objective of evaluating the

validity and reliability of the theories, claims, and applications of these

models. Coffield et al. (2004) found the reliability and validity of the

learning style inventory and learning cycle to be questionable. For example,

matching teaching style with learning style does not improve academic

achievement (Coffield et al., 2004). Despite this, the value of using Kolb’s

theory to guide library instruction is that it provides a theoretical framework

to guide practice to use past experiences in present teaching, and to provide

time for reflection and abstract conceptualization (critical thinking) as well

as time for active experimentation (testing ideas and theories). It is also learner-centered

and reminds instructors to teach to a variety of learning styles in the

classroom.

Active experimentation

We

decided to experiment with team teaching for Lesson Two. Having two instructors in the room enabled us

to use each other’s strengths and expose the students to two different styles

of teaching, thereby appealing to more learning styles in the classroom. Two

librarians in the classroom enabled us to monitor students’ completion of tasks

and to ask them to show us how they applied what they learned to the learning

activities. We and the faculty facilitator observed that the students in Lesson

Two appeared more engaged in learning activities, reflection, and discussion.

Student feedback was consistently positive in both Lesson One and Lesson Two.

Limitations and

Next Steps

The

amount of time required to implement Kolb’s theory was an issue. Because the

delivery of certain content was required, there was insufficient time to incorporate

the reflection and abstract conceptualization required for a true experience of

Kolb’s cycle of learning. That we saw the students only once also limited our

opportunities for follow-up on student engagement, and subsequent adjustment of

our teaching strategies. Another limitation is that we did not randomly assign

students to a control group, taught without applying Kolb’s theory, and an

experimental group, taught applying Kolb’s theory, to measure any differences

in student satisfaction or achievement of learning outcomes. The results

observed during this process were based on our reflection and our perception of

our performance and the impact on student engagement. There was no objective

measurement of student engagement or teaching effectiveness.

This

paper focused on our reflective practice and perceptions of the

teaching-learning process as we incorporated Kolb’s theory into library

instructional practice. Future researchers may want to focus on gathering

empirical data in order to measure student satisfaction with information

literacy skills instruction when librarians incorporate various learning

theories into their teaching practice. Interested researchers may also want to

compare the effectiveness of using Kolb’s theory on student learning outcomes

and comparing that to when librarians use another adult learning theory to

guide teaching practice.

Conclusion

In

this observational study we incorporated adult learning theory into two

distinct lesson plans, delivered to two groups of students from the same

program, completing the same assignment.

Four types of qualitative feedback appeared to affirm that there were

improvements in student engagement from Lesson One to Lesson Two. It appeared

that the effective incorporation of Kolb’s theory resulted in greater student

engagement and a more collaborative classroom environment. Additionally, we

experienced a transformation as teachers. We became more thoughtful,

deliberate, and aware of our teaching purpose and goals and their potential effect

on student engagement. The incorporation of multiple teaching strategies that

address a variety of learning styles enabled us to facilitate the students

moving through the cycle of learning in order for knowledge creation to occur.

Applying theory to practice increased our knowledge of adult learning theory

and teaching practice, challenged our beliefs that we were already effective

instructors, and motivated us to try new strategies that we had not considered,

such as team teaching and being observed by a peer and a faculty facilitator.

This study motivated us to change our practice to enhance student engagement

and to develop into more effective information literacy instructors.

References

Bergsteiner, H.,

Avery, G. C., & Neumann, R. (2010). Kolb's experiential learning model:

Critique from a modeling perspective. Studies in Continuing

Education, 32(1), 29-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01580370903534355

Bowles-Terry, M.

(2012). Library instruction and academic success: A mixed-methods assessment of

a library instruction program. Evidence Based Library & Information

Practice, 7(1), 82-95. Retrieved from http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP/article/view/12373/13256

Clem, J.M.,

Mennicke, A.M., & Beasley, C. (2014). Development and validation of the

experiential learning survey. Journal of

Social Work Education, 50(3), 490-506. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2014.917900

Coffield, F.,

Moseley, D., Hall, E., & Ecclestone, K. (2004). Should we be using learning

styles? What research has to say to practice. Retrieved from http://www.itslifejimbutnotasweknowit.org.uk/files/LSRC_LearningStyles.pdf

Cox, L.,

Clutter, J., Sergakis, G., & Harris, L. (2013). Learning style of

undergraduate allied health students: Clinical versus classroom. Journal

of Allied Health, 42(4), 223-228. Retrieved from http://www.asahp.org/publications/journal-of-allied-health/

Crookes, K.,

Crookes, P. A., & Walsh, K. (2013). Meaningful and engaging teaching

techniques for student nurses: A literature review. Nurse Education in

Practice, 13(4), 239-243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.04.008

D'Amore, A.,

James, S., & Mitchell, E. K. (2012). Learning styles of first-year

undergraduate nursing and midwifery students: A cross-sectional survey

utilizing the Kolb Learning Style Inventory. Nurse Education Today, 32(5),

506-515. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2011.08.001

Devasagayam, R.,

Johns-Masten, K., & McCollum, J. (2012). Linking information literacy,

experiential learning, and student characteristics: pedagogical possibilities

in business education. Academy of Educational Leadership

Journal, 16(4), 1-18. Retrieved from http://www.alliedacademies.org/academy-of-educational-leadership-journal/

Halcomb, E.,

& Peters, K. (2009). Nursing student feedback on undergraduate research

education: implications for teaching and learning. Contemporary Nurse: A

Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession, 33(1), 59-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.5172/conu.33.1.59

Kolb, A.Y &

Kolb, D.A (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: enhancing experiential

learning in higher education. Academy of

Management Learning and Education, 4(2), 193-212. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2005.17268566

Kolb, D.A.

(2014). Experiential learning: Experience

as the source of learning and development (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle

River: Pearson.

Lange, J.,

Canuel, R., & Fitzgibbons, M. (2011). Tailoring information literacy

instruction and library services for continuing education. Journal of Information Literacy 5(2), 66-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.11645/5.2.1606

Lisko, S.A.

& O’Dell, V. (2010). Integration of theory and practice: Experiential

learning theory and nursing education. Nursing Education Perspectives 31(2),

106-108. Retrieved from http://www.nln.org/newsroom/newsletters-and-journal/nursing-education-perspectives-journal

Schilling, K.,

& Applegate, R. (2012). Best methods for evaluating educational impact: a

comparison of the efficacy of commonly used measures of library

instruction. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 100(4),

258-269. http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.100.4.007

Woods, H. B.

(2012). Know your RO from your AE? Learning styles in practice. Health Information & Libraries Journal,

29(2), 172-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2012.00983.x

![]() 2015 Ha and Verishagen. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Ha and Verishagen. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.