Article

A Mixed Methods Approach to Assessing Roaming

Reference Services

Consuella Askew

Director

John Cotton Dana Library

Rutgers University–Newark

Newark, New Jersey, United

States of America

Email: consuella.askew@rutgers.edu

Received: 15 Feb. 2015 Accepted:

13 May 2015

![]() 2015 Askew. This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2015 Askew. This is an Open Access article distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective

–

The objectives of this research are threefold: a) to assess the students’

perception of the roaming service at the point of service; b) to assess the

librarians’ perception of the service; and, c) to solicit librarian feedback

and observations on their roaming experience and perceived user reactions.

Ultimately, this data was used to inform and identify best practices for the

improvement of the roaming service.

Methods

–

A combination of quantitative and qualitative survey methodologies were used to

collect data regarding patron and librarian service perceptions. Patrons and

librarians were asked to complete a survey at the conclusion of each reference

transaction. In addition at the end of the first semester of the

implementation, librarians were asked to provide feedback on the overall

program by responding to five open-ended questions.

Results

–

The findings indicate that our students typically seek assistance from the

librarians once a term (58%), but the majority (71%) indicated that they would

seek a librarian’s assistance more frequently, if one were available on the

various floors of the library. Overall, our users indicated that they were

“Satisfied” (36%) to “Very Satisfied” (43%) with the roaming service. Librarian

responses indicate overall enthusiasm and positive feelings about the program,

but cautioned that additional enhancements are needed to ensure the continued

development and effectiveness of the service.

Conclusion

–

Overall, patrons were satisfied with the service delivered by the roaming

reference librarian. The roaming librarians also provided positive feedback

regarding the delivery of service. Data collected from both groups is also in

agreement on two major program aspects needing improvement: marketing of the

service and a means by which to easily identify the roaming librarian.

Introduction

Reference service delivery

has centered on the physical service desk since the late nineteenth century

(Miles, 2013, p. 323). However, even pioneering library thinkers such as Samuel

S. Green saw the need to decentralize reference service delivery and untether

the reference librarian from the desk. In one of his classic publications

concerning patron–librarian relations, Green asserts: “One of the best means of

making a library popular is to mingle freely with its users, and help them in

every way.” (Pena & Green, 2006, p. 164). Over the years, reference service

delivery has evolved in tandem with emerging information and communications

technology. Reference librarians have expanded their reach beyond the desk by

interacting with patrons using multiple modalities such as by phone, fax, email

and now via the web, text and SMS. As noted by Askew and Ball (2014): “The use

of technology has empowered reference librarians to move away from reference

‘as place’ services and enabled them to provide focused service at point of

need” (p. 119). Today, mobile technologies such as iPads, cell phones,

smartphones, and laptops are being employed successfully to deploy roaming or

roving services in public and academic libraries to provide reference services

to the patrons where they are.

Such is the case at Florida International

University (FIU) Libraries. To better accommodate the information needs of the

students in a library building with severely limited available seating, the

Information & Research Services librarians instituted a roaming reference

service. In the literature, the terms roaming and roving have been used

interchangeably when referring to reference services physically delivered

beyond the desk. As a professional preference, the FIU reference librarians

preferred to be referred to as “roamers” rather than “rovers”. Therefore the

term “roam” and its variant forms will be used throughout this article when

referring to the FIU roaming service.

FIU Libraries Roaming Reference

The FIU Libraries system is comprised of two

libraries, the Steven and Dorothea Green Library located on the Modesto A.

Maidique Campus and the Glenn Hubert Library situated on the Biscayne Bay

Campus – approximately 30 miles apart. Despite the different geographic

locations, the libraries share common service challenges that are inherent to

primarily commuter-based populations. Reference services provided across both

libraries include the traditional desk, in-depth one-on-one research

consultations, phone, email, and growing chat and texting services. Despite

this array of service options, results from a previous internal library survey

attempting to discern users’ preferred mode of interaction revealed users still

preferred face-to-face interaction. These types of interactions have become

increasingly difficult as seating in the libraries – particularly, in the Green

Library – has become even scarcer. Students are reluctant to leave their seats

to seek the assistance of a librarian at the reference desk for fear of not

being able to reclaim their seat upon their return and have taken to Twitter to

express their concerns about the lack of seating in the libraries. The number

of in-house initiated chat sessions serves as further evidence of their

reluctance to leave their study space. Growing user expectations for ubiquitous

service and the continued evolution of information and communications

technologies has dictated the need for increased flexibility and mobility in

the delivery of the libraries’ reference services. The “Ask-Us-Anywhere”

roaming reference pilot iPad program was developed in an attempt to respond to

user needs and expectations of the libraries’ reference services, with the

added benefit of providing at-point-of-need service.

A total of 12 volunteers for the pilot iPad roaming

service were recruited from across the libraries: 5 at the Hubert Library and 7

at the Green Library. In order to participate in the program, librarians agreed

to roam for two hours each weekday during the peak hours, between 10:00 a.m. to

2:00 p.m. on the day(s) of their choosing. A shared calendar was created to

facilitate the scheduling of the service across libraries. Due to limited

weekend staffing, roaming was not provided on Saturdays and Sundays. Roamers

were encouraged to roam within or outside of the library buildings and were

expected to represent the libraries at student and faculty orientations and

other events across the university. In order to receive their iPads,

participants were required to attend a training session to familiarize

themselves with the iPad and recommended software applications prior to their

first day of roaming.

The iPad 2 was selected as the device of choice for

the roamers primarily because of its easy mobility. The device allowed full

access to the web, the online catalogue and other library resources including,

research guides, library FAQs, databases, and the libraries website. Funding

for the iPads was secured through a Student Technology Fee grant awarded by the

university. Given the nature of the iPads as personal devices, as well as the

scheduling difficulties that would arise from sharing devices across campuses

and busy schedules, the program coordinators decided to assign each librarian

their own iPad. Therefore, grant funds were used to purchase 12 iPad 2s, 12

wireless keyboards, and 12 OtterBox protective cases.

To supplement the training sessions, an Ask Us Anywhere: iPad Roving/Roaming LibGuide

was created. The workshop, as well as the guide, covered the basics of device

usage, the setup of their individual accounts, network and wireless access,

installation of apps, bookmark suggestions, and how to collect service

assessment data. Guidelines for best practices on how to approach patrons and

what to do when roaming were also addressed using roaming etiquette and

techniques compiled from researching the library literature and business-related

literature (Askew & Ball, 2013).

Aim

The objectives of this research were threefold: a) to

assess the students’ perception of roaming service at the point of service; b)

to assess the librarians’ perception of the service at point-of-need; and, c) to

solicit librarian feedback and observations on their roaming experience and

user reactions. Ultimately, the findings were used to inform and identify best

practices for the improvement of the roaming service.

Review of the Literature

In its earliest form, as described by Samuel Green,

roaming reference consisted of librarians who would walk around the library to

identify and assist patrons in need. However, the proliferation of electronic

and web-based information impeded the librarian’s ability to easily access

information while away from the reference desk – and their computer work

station. Kramer (1996) notes that this challenge was resolved as libraries

increased their numbers of stand-alone OPAC terminals, which were strategically

scattered throughout the library buildings. As electronic information became

mobile in the first decade of the new millennium, tablet PCs were incorporated

into the delivery of roaming reference services with mixed results (Hibner,

2005; Smith & Pietraszewski, 2004). Next came the integration of

smartphones, particularly the iPhone, but problems with connectivity, screen

size, non-standardization, formatting, and functionality prevented the early

generations of this technology from being adopted on a long term basis (Murray,

2008). However, Apple’s introduction of the iPad in 2010 provided a mobile and

lightweight technology that librarians were quick to adopt for their roaming

services. Given its relatively short lifespan, a review of the literature

published during the years 2010-2015, reveals little has been published about

utilizing iPads for roaming reference services substantiating the findings of

Maloney and Wells (2012) who noted in their literature review, that they found

only a “handful of scholarly titles, with most focusing on roving reference”

(p. 12).

Perhaps, the most thorough iPad roaming reference

study to date was conducted by McCabe and MacDonald (2011) at the University of

Northern British Columbia. Using roaming reference as a way to address their

declining reference statistics, their librarians staffed the service for six

months, during which time they collected transaction data for query type,

location and approach. Two iterations of the roaming service were implemented:

one integrated with the traditional service desk duties and the other as a

standalone service. The latter iteration required librarians to provide roaming

service in addition to their reference desk hours. Patrons were asked to

complete an optional e-questionnaire at the end of the roaming transaction to

collect data related to past use of reference services, provide thoughts on the

service and to find out whether or not the service made them more apt to

contact a librarian for help.

The library realized an overall increase of 228 reference

questions with the roaming service; the majority of which (67%) were

research-related. The results indicated that the roving reference service with

iPads proved to be very successful when librarians were only assigned to rove,

but less successful when they combined desk hours with their roving duties.

They found that the integration of roaming and reference desk services resulted

in a 56% decline in the total number of roaming reference questions from the

previous iteration where roaming was implemented in addition to desk hours.

Although they indicated that they did collect patron data, an analysis of that

patron data was not presented.

The Youth Services (YS) division at the Boise Main

Public Library received a Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA)

Just-in-Time grant that allowed them to acquire four iPad2s for nine staff

members to provide a roving reference service (May, 2011). The intended goal

was to increase staff interaction with patrons, by giving them tools that

allowed them to move away from the reference desk. Although they kept their

traditional reference desk, the use of the desk was minimized as they added

more roving personnel.

As a result of the service, they were able to have

multiple librarians assisting multiple patrons at the same time using the staff

features of the catalogue. They also learned that their web-based public access

catalogue was not optimized to work with mobile technologies. Other complaints

such as ergonomic issues with long-term use of the device, the lack of ease

when switching back and forth between applications and cutting and pasting were

also common. Based on their experience, it was recommended that each librarian

should have her or his own device to allow for the personalization of the applications

and other customization (May, 2011, p. 14). Unfortunately, May did not provide

any assessment data regarding this program.

At the University of Warwick Library, Widdows (2011)

recounts their roving reference experiences using the mobile phone and their

trial of the iPad as a potential roving tool. The Warwick library does not have

a traditional reference service desk, but utilizes HelpDesks, which deal

primarily with circulation and account questions as a means of proving query

“triage”. The HelpDesks refer patrons to “specialists staff”, or rovers, as

needed. The rovers also provide backup support to the HelpDesks during peak

times.

Their iPad trial lasted one week (35 service hours).

Fifty-six of the total 230 HelpDesks queries were handled by the rovers and 26

of these required the use of the iPad. Widdows noted the major challenge with

using the iPad was the lack of a phone feature which prohibited the rovers from

contacting a specialist for more complex queries. As with the Boise library,

the Warwick librarians also ran into problems accessing the full features of

their web-based catalogue on the iPad. Although Widdows states that they

collected data on their roaming program, other than the few transaction

statistics shared above, there was no other data presented to illustrate an

assessment of the users’ or the rovers’ perspectives about the program.

At Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, Morris

Library, three iPads were integrated into an existing roaming program (Lotts

& Graves, 2011). Nine reference librarians shared usage of the iPads, which

were checked out in shifts. The benefits of using the iPads included the

Virtual Librarian being mobile while staffing the virtual reference service and

the multi-functionality of the iPad which was ideal for reference, enabling

access to the online catalogue, reference tools, and serving as an eBook

reader. The drawbacks noted by the authors presented some surprises. The

literature typically reflects that roaming librarians tend to prefer the

lighter, more mobile iPad, to the laptop. However, at this library, the

librarians reported feeling “uncomfortable” with the iPad as a replacement for

the laptop. In agreement with May’s recommendation, the authors thought that

each roamer should have his or her own iPad to minimize the need for continual

account management and allowing individual to customization for their specific

needs. Lotts and Graves did not present any transactional or assessment data of

any kind, they explained the omission in their “Next steps and the future”

section of the article, by saying that assessment and usage data will be

compiled and analyzed as part of their next steps in determining how the

library moves forward with their roaming service (p. 220).

Librarians at the Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery

collected two semesters of data about their iPad roaming service, which

operated for four hours per week in predefined campus locations (Gadsby &

Qian, 2012). The roaming locations were identified through observing traffic

patterns in their 24-hour library study space, the commuter lounge, the

University Center and academic department offices.

Using transaction data for 60 queries, they determined

that more than 75% of the service users were students, the busy times of the

week were Tuesday through Thursday from 2:00 p.m. – 4:00 p.m., and more than

half of the questions they received were library-related. Although they mention

anecdotal feedback they received from their campus community, there was no

attempt to formalize a data collection effort to capture and analyze this

qualitative data. Furthermore, there was no mention of future assessment

efforts.

The roaming programs identified in the literature

shared a number of commonalities across library types such as: reference

librarians being able to provide services beyond the reference desk; the

provision of just-in-time service; the ability to access web-based library

resources away from the desk; and, library staff being able to access multiple

instances of their online catalogue in order to assist large crowds of users

(May, 2011; McCabe & McDonald, 2011; Widdows, 2011). The statistics

collection and tracking for these iPad roaming programs vary widely by method

and scope. The noted challenges of these programs included using mobile devices

to access full functionality of the online catalogue, unstable wifi

connectivity, and statistics recording (May, 2011; McCabe & McDonald, 2011;

Widdows, 2011).

The literature indicates that the experimenting

libraries – academic and public – have had overall positive experiences with

integrating the iPad into their roaming services. However, it also reveals that

very little assessment data has been collected on iPad roaming programs. While

three of the five articles discussed above present mostly transactional or

usage data, none provided any type of assessment data – empirical or otherwise –

to represent program effectiveness, user satisfaction or feedback. This study

attempts to fill this existing gap in the literature and create a foundation

upon which to build assessment techniques for roaming services using mobile

devices.

Methodology

Surveys were used to collect data from the user and

the librarian immediately after the roaming transaction was completed. The

survey instruments were created using Qualtrics, a web-based survey tool

licensed by the university and were bookmarked on the roamers’ iPads for easy

access. In order to encourage participation, the instruments were designed to

be very brief; the user survey consisted of four items and the librarian survey

had two items. The survey items were piloted by a small group of faculty and

students before they were put to use. To allay any concerns about privacy,

users were advised that their responses were confidential and that once they

clicked on the survey submit button, all responses would be recorded and

disappear before the iPad was handed back to the librarian. After the user

completed the survey, the librarian would then complete the corresponding

librarian survey for that transaction. The data collected from both surveys

reside behind a firewall on a secure university server.

The roaming service coordinators collected feedback

about the program from the librarians via email asking them to respond to five

questions concerning the service implementation, user reception, suggestions

for improvement and an open-ended question for any additional comments they may

have had about the program.

Results

The survey data collection period lasted 52 days

(approximately 10 weeks) for a total of 208 service hours during the beginning

of fall 2011. The roaming service and data collection efforts were conducted

during the libraries’ peak hours between 10:00 a.m. - 2:00 p.m., Monday through

Friday. During that time the reference librarians responded to a total of 2,850

(N) queries via our virtual/mobile services that include chat/IM, SMS/Text,

telephone, email, and phone. Reported roaming reference transactions totalled

168 queries (n=168), which represents

5.9% of the total number of these virtual/mobile transactions.

Quantitative Results

A deeper analysis of transaction data recorded in our

LibAnswers system provided us with useful information not only about the

program, but also about our library users. The data show that our roamers were

most often inside the library (89%), when a transaction occurred. The majority

(79%) of the service users were undergraduates. The nature of the roaming

queries were most likely to be directional/informational (73%), followed by

research-related (20%) and least likely to be technology-related (7%). The

overwhelming majority (88%) of the transactions took between one to ten minutes

to complete.

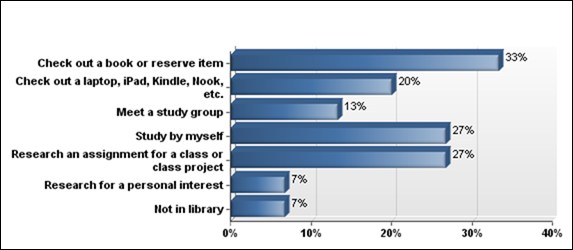

The student surveys (n=15) completed upon the conclusion of a transaction, provided

insight to user behaviour and their satisfaction levels with the service. When

asked why they were in the library on that day, the largest percentage (33%) of

users responded that they were there to check out a book or reserve an item.

The second most frequent response was that they were in the library to “study

by themselves” (27%) or to “research an assignment for a class or class

project” (27%). The third highest response showed that the reason users were in

the library that day was to check out an electronic device (21%) such as a

laptop, iPad, Kindle etc. (See Figure 1)

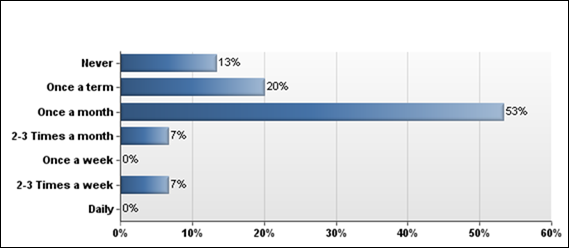

Figure 2 shows the majority of the respondents

indicated that they asked a librarian for assistance about once a month.

The third survey item collected data regarding user

satisfaction with elements of the roaming program using a Likert type

satisfaction scale (See Table 1) with 5=Very Satisfied and 1=Very Dissatisfied.

In particular, we wanted to know if the roaming librarians were friendly and

approachable, if they were easily identifiable and, of course, if the user

received the help they needed. Since there were no negative responses, only the

positive responses are represented in the table. Forty-seven percent of the

respondents indicated that they were “Very Satisfied” and the librarian who

assisted them was approachable and friendly; however, 20% of the respondents

indicated they were “Neutral”. Over half of the respondents (60%) indicated satisfaction

with the ease by which they could recognize the librarian as a library employee

and with the help that they received. However, only a third (33%) of the

respondents indicated being “Very Satisfied” with the ease by which they could

recognize the librarian as a library employee and 7% gave “Neutral” rating to

this same item indicating a program need.

Figure 1

Purpose of library visit.

Percentages do not equal 100%, since users were asked to check all responses

that applied to them.

Figure 2

How often user asks for librarian assistance

The last survey item asked if the respondent would be

more willing to ask for assistance if a librarian were available on the various

floors of the library, to which 73% responded “Yes”. The low number of user

responses prevents us from gathering any meaningful information from a cross

tabulation of the responses to this item with survey item #2 regarding their

frequency of asking assistance, to find out if there is a relationship between

the respondents who tended to ask a librarian for help more often and those who

would be more likely to seek assistance from a librarian posted on the various

floors of the library throughout the day.

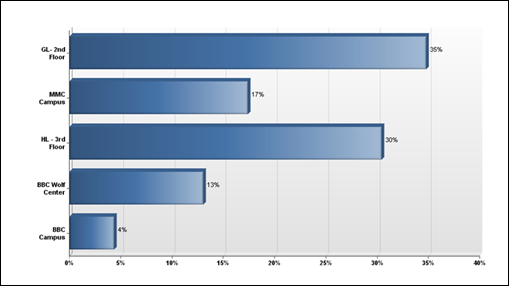

The responses to the Librarian surveys (n=23) provided insight into their

behaviour while roaming. The librarians indicated that they typically

approached the student (74%). There seemed to be two most common roaming

locations between both campuses: the second floor of Green Library (35%) and

the third floor of Hubert Library (30%). (See Figure 3)

Table 1

User Level of Service

Satisfaction

|

Question |

Very Satisfied |

Satisfied |

Neutral |

|

Librarian was approachable and friendly |

47% |

33% |

20% |

|

Librarian was easily recognized as a library

employee |

33% |

60% |

7% |

|

I got the help I needed |

40% |

60% |

0% |

Figure 3

Roamer frequented locations

The Librarians’ response to the survey item asking

them to rank how they felt the user’s level of satisfaction was with their

assistance indicated that a little over half (52%) felt their user was

“Satisfied” with the services received, a few indicated their users were “Very

Satisfied” (22%) with their assistance.

Qualitative Results

While the quantitative data primarily focused on the

users’ behaviours, the qualitative data does the same for the librarians who

roamed. The qualitative data collected from all 12 librarians provided useful

suggestions for changes to the services from the people on the front line

interacting with the patrons. As the quantitative data showed, roamers

indicated a preference for roaming in one of two places in and around the Green

and Hubert Libraries. Surprisingly the comments for the favourite spot in the

Green Library, the third floor, differed from the recorded transaction

locations, which mostly took place on the second floor of the library where the

reference desk was located. The Green Library librarians indicated that they

liked to roam on the third and seventh floors, as these floors have no service

desk. Since the Hubert Library has fewer floors than the Green Library, the

librarians roamed in the library, as well as in the nearby academic buildings

and the student center where the students tend to congregate. One of Hubert Library

librarians shared that they roamed

…through the library and around the WUC [Wolf

University Center]. Sometimes through AC1 [Academic Center 1]…Because the

library is too small and I often find I get more questions outside of [sic]

library.

The challenges identified from the FIU experiences

were unique compared to those found in the literature and included excessive

noise levels, extreme temperatures in certain locations and poor recognition or

visibility of the service. One librarian commented on feeling a “little

intrusive” when roaming a floor where the students are quietly studying saying:

I must admit that sometimes, when it is very quiet and

students are busily engaged, I feel a little intrusive and somewhat like a

floor walker.

Figure 4

Roamers' rating of user's

service satisfaction level. Using the same Likert type satisfaction

scale as with the previous items, there were no negative responses recorded and

these are therefore not represented in this figure.

Although at the end of the comment, the concluding

sentiment was that perhaps it was “Just my hang up, of course.” Another librarian

expressed the difficulty of having students feel comfortable with approaching

them for help stating:

The most challenging aspect so far has been having the

students approach us for help. You can usually find students who need help if

you ask them, but they will not approach us themselves.

A number of free applications were suggested and

recommended for use by the roamers during the roaming service training session

and the roamers were taught how to install and use these apps on their iPad. Most

of the roamers report that rather than using the apps, they used bookmarks more

frequently instead. One of the more ambitious and tech savvy roamers indicated

using applications such as “prezi viewer, dropbox (most often), and adobe

reader” as well.

The majority of the roaming librarians agreed that the

service needed better publicity and marketing to raise the students’ awareness

of the service and help them easily identify roamers when they needed one. As

one librarian commented, the service needed to be more “high profile”. However

it became clear through other comments that along with the high profile there

was a need to implement a “consistent schedule”.

When asked to look into the future and share their

vision of our roaming service one to two years from now, all but one roamer

indicated that they saw this service existing alongside the traditional

reference desk as opposed to a standalone service. In comment after comment, it

was clearly and strongly expressed that the traditional reference desk should

continue to be a point of service for reference. Such assertions included the

following:

I believe the desk will always be needed

As a traditionalist, I like the idea of having a

reference desk. I think people need to identify a specific place where they can

go for help.

Roaming should not replace the reference desk: it’s an

extra way to help people.

However, one librarian saw things a bit differently:

I see reference increasingly decentralized, online,

ubiquitous, and continuous….

When asked to provide any additional comments they had

about the service, they unanimously presented overall positive and enthusiastic

feelings about their service experience:

I’ve enjoyed it quite a bit, and believe this and

online help are closer to the future of reference services than sitting at a

desk.

There is great potential with this service. We just

have to keep tweaking.

The students are always very happy when they receive

help right where they are.

Discussion

The reference transaction data recorded in LibAnswers

showed that the respondents who received assistance from a roamer were more

likely to be an undergraduate student and were in the library to check out a

book or reserve material. This indicates that they were more likely to interact

with library staff at the access services desk(s) than with those stationed at

the reference desk. This also means they were less likely to need to seek out a

reference librarian for research assistance. When users were provided

assistance by a roamer, it was the roaming librarian who approached the student

to initiate the reference transaction more often than not. Student responses concerning their

recognition of the roamers as a library employee validated the librarians’ suggestions

regarding the need to improve the identification of librarians while away from

the reference desk and to improve the service publicity and marketing

strategies.

Although library personnel have nametags they are not

required to wear them. The “Ask me” tag attached to the lanyards worn by the

roamers tended to hang lower than the line of sight and was therefore easily

overlooked by potential users. Alternatives discussed included creating a

button, wearing hats, or wearing other outerwear that would clearly show the

“Ask Me” logo to encourage users to approach the roamers for assistance. The

program publicity consisted of an announcement on the libraries’ website,

social network venues and advertising the service on the libraries’ internal

digital signage displays. The roamers agreed that more should be done to raise

the visibility of the program. In addition to the above, ideas included

creating a more attractive and engaging sign for the libraries’ digital

display, highlighting this service more prominently on the libraries’ homepage

as well as promoting the service in the student newspaper.

Given the students’ reluctance to ask a librarian for

help, it was encouraging to see users respond that they were most often

satisfied with the help they received from the roamers and with their overall

experience. While most (80%) of the respondents indicated that they were “Very

Satisfied” and “Satisfied” with the librarian being approachable and friendly,

20% responded “Neutral” to this item. These responses may suggest that roamers

be more aware of their body language and facial expressions when approached by

a student, or when approaching them. What was most encouraging was that the

respondents indicated they would be more likely to seek assistance from a

librarian if one were available on the various floors of the library. This

indicates that the roaming service has high impact potential and signifies a

need to redefine the program service strategy. As several roamers noted, the

service needs to be provided on a more consistent schedule and perhaps in

conjunction with the reference service desk schedule.

All of the above factors, along with the abbreviated

service hours, most likely contributed to the low response rate to the

quantitative surveys. While the data presented in this article may not be

generalizable to other libraries, it does serve as an indicator for students’

receptiveness and potential use of a fully implemented roaming service by the

FIU Libraries. Overall, the data indicates that the FIU Libraries’ roaming

service fulfilled a need and that students would use the service if were

offered as part of a suite of reference services.

Based on the librarians’ survey responses it is

noteworthy that the GL librarians, unlike the HL librarians, preferred to roam

on the floor where the reference desk is located. Especially so, since the

Green Library has eight floors - six of them providing open study spaces –

whereas, the Hubert Library only has three floors. A comparison of the service

data between the roamers and the users presented an interesting revelation. The

users reported being much more satisfied with the service they received than

the librarians perceived them to be. This suggests that as service

professionals, librarians set a higher bar for service delivery for themselves,

than is actually expected by the patrons.

Although there were a number of common challenges

cited in the literature about providing an iPad roaming service, very few of

these challenges were mirrored by the data collected from the FIU roamers. The

challenges experienced by the librarians were unique to the FIU Libraries and

included excessive noise levels, extreme temperatures in certain locations, and

poor recognition or visibility of the service. The latter challenge was further

exemplified by the statistics indicating that the librarian most often

initiated the roaming transactions.

There was quite of bit of time spent on identifying

appropriate and relevant iPad applications for the service along with the

appropriate training for their use. However, the majority of the librarians’

responses revealed that they preferred to use bookmarks instead of the apps.

This preference bears further investigation to determine why that was the case.

A subsequent iteration of the roaming service model

implemented in the following academic year which integrated the service with

the reference desk as was suggested after the pilot was considered

unsuccessful. Of particular concern with the new model was determining an easy

and reliable method of communication (i.e., realtime chat, SMS/Text, Facetime,

etc.) between the user and the librarian at the reference desk so that a roamer

can be efficiently dispatched. In the spring of 2014, the roaming service was

placed on hiatus until the Information & Research Services departments can

identify and come to a mutually agreed-upon solution.

Conclusion

Roaming reference is not new in academic libraries and

the integration of mobile technologies has provided even more opportunity for

academic librarians to become “unchained” from the traditional desk to meet

their users at the point-of-need. As reference services become more

decentralized and personalized, researching the effect of roaming services may

be valuable to inform the overall quality of service as perceived by the user.

Askew and Ball (2013) identify a need for further research to determine to what

extent does culture, language or gender impact a library user’s willingness and

comfort level to approach a librarian for help. They also state more research

is needed to determine how these same factors affect librarians’ comfort level

when approaching users. When focusing on the technologies employed in roaming

reference services such as iPads, there is need to determine what

functionalities, features and apps are most necessary or useful when responding

to queries at the point-of-need.

There are always two sides to every story. In addition

to gathering data from our patrons, there is also a need to gather data from

roaming librarians (staff) in a more formal way. Askew and Ball (2013) note:

“…academic libraries should consider not so much the ‘what’ we do, as

illustrated by the traditional reference transactional data collected, but

should also incorporate data collection to describe who we serve, how we serve

them, and where we serve them” (p. 98). Conversely, we should also take into

account what services our users tell us they want, along with how and where

they want to receive them. The two may not always be in agreement. In order to

accomplish this in a comprehensive fashion necessitates using assessment

methods and measures looking from the outside in, by obtaining data not only

about the patron, but also about the librarian to capture and reveal the

complete story.

References

Askew, C., & Ball, M. (2013). Telling the whole story: A mixed

methods approach to assessing roaming reference services. In S. Hiller, M.

Kyrillidou, A. Pappaloardo, J. Self, & A. Yeager (Eds). Proceedings of the 2012 library assessment

conference building effective, sustainable, practical assessment.

Association of Research Libraries Library Assessment Conference, Charlottesville,

VA. (pp. 91-101). Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries. Retrieved

from http://libraryassessment.org/bm~doc/proceedings-lac-2012.pdf

Askew, C., & Ball, M. (2014). Transforming Reference Services: More

than meets the eye. In C. Forbes & J. Bowers, (Eds.). Rethinking

Reference Services in Academic Libraries, (pp. 117-134). Lanham, MD: Rowman

& Littlefield.

Gadsby J. & Qian, S. (2012). Using an iPad to redefine roving

reference service in an academic library. Library

Hi Tech News, 29(4), 1-5. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07419051211249446

Hibner, H. (2005). The wireless librarian: Using tablet PCs for ultimate

reference and customer service: A case study. Library Hi Tech News, 22(5), 19-22. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/07419050510613819

Kramer, E. H. (1996). Why roving reference: A case study in a small

academic library. Reference Services Review, 24(3), 67-80. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb049290

Lotts M., & Graves S. (2011). Using the iPad for reference service:

Librarians go mobile,” College &

Research Library News, 72(4), 217- 220.

Maloney, M. M., & Wells, V. A. (2012). “iPads to enhance user

engagement during reference interactions. Library

Technology Reports, 48(8), 11-16.

May, F. (2011). Roving reference, iPad-style. The Idaho Librarian, 61(2):

Retrieved from https://theidaholibrarian.wordpress.com

McCabe, K. M., & MacDonald, J. R. (2011). Roaming reference: Reinvigorating

reference through point of need service. Partnership: The Canadian Journal

of Library & Information Practice & Research, 6(2), 1-15. Retrieved from https://journal.lib.uoguelph.ca/index.php/perj/index#.VVzVM-DbLIU

Miles, D. B. (2013). Shall we get rid of the reference desk?” Reference & User Services Quarterly, 52(4),

320-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/rusq.52n4.320

Murray, D. C. (2008). “iReference: Using Apple’s iPhone as a reference

tool. The Reference Librarian, 49(2), 167-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763870802101419

Pena, D. S., & Green, S. S. (2006). Personal relations between

librarians and readers. Journal of Access

Services, 4(1/2), 157-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J204v04n01_12

Smith, M. M., & Pietraszewski, B. A. (2004). Enabling the roving

reference librarian: Wireless access with tablet PCs. Reference Services

Review, 32(3), 249-255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320410553650

Widdows, K. (2011). Mobile technology for mobile staff: roving enquiry

support. Multimedia Information &

Technology, 37(2), 12-15. Retrieved from http://www.cilip.org.uk/multimedia-information-and-technology-group/mmit-journal-0