Article

A Survey of Graphic Novel Collection and Use in

American Public Libraries

Edward Francis Schneider

Assistant Professor

University of South Florida,

School of Information

Tampa, Florida, United

States of America

Email: efschneider@usf.edu

Received: 27 Dec. 2013 Accepted: 16

July 2014

![]() 2014 Schneider. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2014 Schneider. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – The objective of this study was to survey

American public libraries about their collection and use of graphic novels and

compare their use to similar data collected about video games.

Methods – Public libraries were identified and contacted

electronically for participation through an open US government database of

public library systems. The libraries contacted were asked to participate

voluntarily.

Results – The results indicated that both graphic novels

and video games have become a common part of library collections, and both

media can have high levels of impact on circulation. Results indicated that

while almost all libraries surveyed had some graphic novels in their

collections, those serving larger populations were much more likely to use

graphic novels in patron outreach. Similarly, video game collection was also

more commonly found in libraries serving larger populations. Results also

showed that young readers were the primary users of graphic novels.

Conclusion – Responses provided a clear indicator that

graphic novels are a near-ubiquitous part of public libraries today. The

results on readership bolster the concept of graphic novels as a gateway to

adult literacy. The results also highlight differences between larger and smaller

libraries in terms of resource allocations towards new media. The patron

demographics associated with comics show that library cooperation could be a

potential marketing tool for comic book companies.

Introduction

The inclusion of

graphic novels and video games in libraries is not a new phenomenon. By 1934,

issues of Max Gaines’ Funnies on Parade and Famous Funnies: A

Carnival of Comics found their way onto library shelves across America, and

by 1982, video games had done the same (Holston, 2010, p.10; Emmens, 1982). As

the 80th anniversary of the publication of the first comic book nears,

arguments for and against their presence in libraries have stayed fairly

consistent throughout. Discussion about comic books and video games being

collected by libraries primarily revolves around the value for patrons,

allocation of resources, and organization. To this day, patrons can find

librarians on both sides of the divide when it comes to whether graphic novels

and video games belong in collections.

Comic books and

graphic novels present interesting questions for librarians. Most comic books

are published in a format that resembles a periodical, but graphic novels more

closely resemble novels. For example, the bound version of Watchmen by Moore, Gibbons & Higgins (1986) was named by Time magazine as one of the 100 best

English-language novels published since 1923 (Grossman & Lacayo, 2010), but

Watchmen was originally published as

a series of monthly comics. Besides the periodical/novel question, some popular

cataloguing systems lump all comic books together based on format rather than

publisher or creator. There is plenty of evidence that comic books are in

libraries in various forms, from studies on academic library collection

strength, to books advising how to collect and use comics in libraries.

Information on how libraries use and archive comics and graphic novels, as well

as their impact on library patrons is less readily available.

This study

investigated how American public libraries archive and use comic books and

graphic novels, and asked librarians across the United States about the role of

these materials in their systems. As a point of comparison, the professional

librarians who participated in this survey were also asked similar questions about

the use, archiving, and role, of video games. Both comic books and video games

are newer media forms, have unique cataloguing issues, and have some history of

being frowned upon by parents and educators. The intent of this study was to:

a) create a portrait of how comic books and graphic novels are being used by

working librarians today; and b) compare the status of comic books and graphic

novels within libraries to the status of video games, as a historical benchmark

of new media form adoption.

Literature Review

One of the

earliest and most consistent arguments concerning the collection of comic books

and graphic novels is their legitimacy. Nyberg (2009) notes that upon

discovering comic books in the 1930s, many librarians launched “a crusade to

turn young readers from the lurid ‘funny’ books to more wholesome fare”, and

they were seen as a “problematic form of juvenile sub-literature” (p. 26-27).

This was despite the fact that many early comic books, such as those by Max

Gaines, were collections of strip comics that had previously run in daily

American newspapers with little surrounding controversy. It was these comics being printed for the

first time in the format commonly thought of as a comic book that brought

criticism. In his 1998 paper, A

Practicing Comic Book Librarian Surveys His Collection and His Craft, Randall

Scott, a comic art specialist at Michigan State University, indicates that even

academic libraries that now emphasize comic book collection had collections

influenced by anti-comics sentiment only a few decades prior. While there was

some early opposition to libraries collecting comics, there is also some

history of librarians defending comic book collection against concerned

patrons. A survey of patron challenges to materials in Massachusetts turned up

documents from 1948 detailing a librarian’s defence of her library’s comic book

collection against a Catholic nun requesting the collection’s removal

(Musgrave, 2013).

Many of the

reasons presented to support arguments against the inclusion of comics within a

library collection seemed reasonable at the time. Firstly, the format of

combining illustrations with written words was associated too closely with

children’s picture books, leading many to believe that readers of comics were

not really reading. Secondly, many felt that the violence and sexuality

depicted in some comics would threaten the morals and decency of young readers.

In the early 1950s, psychiatrists such as Dr. Fredric Wertham joined the

debate, arguing that “reading such fare did psychological damage to children”

(Nyberg, 2009, p. 27). Wertham’s work was used as the basis for the Comics Code

Authority, an industry-imposed set of comic decency standards (Nyberg, 2009).

The third argument against legitimacy has been that the “genre” of comics and

graphic novels does not hold up as true forms of literature, particularly when

compared to the classics. To this day, “because the words ‘comic’ or ‘graphic

novels’ still have the stigma of being hack literature many librarians consider

this type of reading material to be inappropriate for the library and resist

its acceptance” (Sheppard, 2007, p.12).

Similar statements

have been made regarding the appropriateness of including video games in library

collections. US Surgeon General C. Everett Koop (1982) expressed serious

concerns about the impact of video games on children’s mental and physical

health. Comic books have also been treated as a public health menace; they were

the subject of a 1948 symposium at the New York Academy of Medicine titled,

“The Psychopathology of Comic Books” (Thrasher, 1949). More current books such

as Stop Teaching Our Kids to Kill: A Call

to Action Against TV, Movie, & Video Game Violence (Grossman &

DeGaetano, 2007) represent common concerns about video games causing delinquent

behaviour. The concerns about video games often resemble the concerns about

comic books in the 1950s. For example, there are many parallels between

Grossman and DeGaetano’s anti-video game book and Dr. Frederic Wertham’s famous

anti-comics book Seduction of the

Innocent: The influence of comic books on today’s youth (1954). Both feature lurid chapter titles, and both

present context-free examples that attempt link increases in real world

violence to the emergence of the new media.

In the 2011

Supreme Court case, Brown v. EMA (2011),

the State of California claimed that “[v]ideo games present special problems

because they are ‘interactive’, in that the player participates in the violent

action onscreen and determines outcome” (p. 9). Judge Posner states in the

courts opinion:

“All literature is

interactive. The better it is, the more interactive. Literature when it is

successful draws the reader into the story, makes him identify with the characters,

invites him to judge them and quarrel with them, or experience their joys and

sufferings as the readers own.” (Brown v EMA, 2011, p. 11)

Justice Scalia

pointed out that this is not the first time this kind of argument has been

made, noting, “…past confusion and alarm about possible harm to minors by penny

dreadfuls (lurid novels), movies, and comic books” (Brown v. EMA, 2011, p. 11).

In the last few

decades, artists and authors of graphic novels have begun tackling more serious

concepts “…such as homosexuality, racism, and AIDS” (Sheppard, 2007, p. 13).

Prime examples are Art Spielgman’s Maus: A Survivors Tale, Craig

Thompson’s Blankets, and Marjane Satropis’s Persepolis. Reading

comics is a complex task of decoding information and making “…relevant social,

linguistic, and cultural conventions” (Tilley, 2008, p. 23). Research has shown

that graphic novels not only help bridge the gap for reluctant readers, but are

“linguistically equal to other works of literature” (Sheppard, 2007, p. 13).

Beyond comprehension of the text at hand, graphic novels can help readers

“…decode mood, tone... facial and body expressions, the symbolic meanings of

certain images and postures, metaphors and similes, and other social and

literary nuances” (Sheppard, 2007, p. 13). Video games, like graphic novels,

range in depth and sophistication. Games such as September 12th and Beyond

Good and Evil are discussed in Buchanan and Vanden Elzen’s (2012) “Beyond a

fad: Why video games should be part of 21st century libraries”. These games

allow users to explore, through a combination of story, visuals, and

interactions, relevant, provocative topics such as “…patriotism, paranoia, and

the role of dissent in a democracy” (Buchanan & Elzen, 2012, p. 18). Some

games such as Alice: The Madness Returns and Batman: Arkham Asylum are

based on books and graphic novels, while some games inspire fiction of their

own, such as Resident Evil and Halo. In a recent article, Levine

(2009) cites Kutner and Olson, stating not only that direct links between real

world violence and video games have been debunked repeatedly, but that “…games

actually help children learn valuable skills such as collaboration,

problem-solving, teamwork, and coping with negative emotions” (p. 34).

As video games

become more prominent, some librarians question what role they have in the

library and how the library’s duties to the public are affected. In a chapter

written for the 2008 Journal of Access Services, the author dismissed

library efforts that included video games and likened them to prostitution of

the library (Annoyed Librarian, 2008, p. 620-621). The author considers adding

video games to collections as a ploy to increase circulation numbers. But in

that same year, the President of the American Library Association spoke

positively of gaming as an social and educational good, and the conclusion of a

2009 American Library Association journal wrote that “…gaming is just one more

way libraries can continue to offer a mix of recreation, social, and communal

activities in a safe, non-commercial space” (Levine, 2009, p. 35).

For libraries that

include graphic novels and video games in their collections, a number of issues

arise, including cost, as well as where and how materials should be shelved and

catalogued. Widespread economic issues have impacted libraries, which have led

to concerns about collection development funds being used for video games and

graphic novels. MacDonald (2013) cites research done by Zabriskie in her recent

article, “How graphic novels became the hottest section in the library”,

regarding the cost per circulation when compared with other popular titles

including Harry Potter, Twilight, and GED guides. Zabriskie found that

graphic novels had higher circulation rates but were also 10 cents less per circulation,

making them considerably more cost-efficient (MacDonald, 2013, p. 22). Online

services, like Comics Plus: Library Edition and Comixology, allow libraries to

utilize an even more cost-effective model for serving materials to patrons

(MacDonald, 2013, p. 25).

These services can

also assist with the other major concern regarding archiving of these

materials, finding space in already crowded library stacks. Hartman (2010)

describes the challenge with comic books as an intersection of limited

resources, limited shelving space and growing patron demand. The Library of

Congress and Dewey systems do little to help librarians in this matter,

clumping all of these materials into the same call numbers regardless of topic.

For graphic novels, Dewey uses 741.5 while Library of Congress splits them

between PS and NC. Video games find themselves clumped either in GV1469 for

Library of Congress or in the 794s for Dewey. “Steve Raiteri noted that graphic

novels should be treated like any other material, taking into account content

and intended audience” (Nyberg, 2009, p. 37). One of the first things that

becomes a problem for graphic novels is the assumption that it is a genre

rather than a format. Once that is sorted out librarians must determine whether

they should be integrated with the topics they cover or grouped together.

Hartman’s opinion and experience at the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library in

Ohio is that patrons prefer not to search through the catalogue and then the

general collection to find what they are looking for. They prefer to browse the

graphic novel section to see what was new and would interest them (Hartman,

2010, p. 59). Additionally, librarians must determine if they separate

collections by age ranges. Collections are commonly split between juvenile, young

adult, and adult. These can be good for general guidelines but many items blur

the line between young adult and adult content. For the Cleveland Public

Library, materials are not only in the central library but also in literature

and young adult sections. While this may increase visibility it may also mean

that users have to find their way to multiple areas of the library to find what

they want (Pyles, 2012, p. 34). Secondly, with the mixture of series and single

volumes, individual titles may get lost in the shelves. To resolve this, some

libraries choose to separate series and single volume items. This allows for

individual titles to not become lost between larger series that sometimes have

thirty or more volumes (Segraves, 2010, p. 70).

Many librarians,

even those who did not grow up with graphic novels and video games, are

“willing to concede legitimacy” due to explosive circulation stats and maturing

content (Hartman, 2010, p. 59). As these materials become more prevalent,

librarians should focus on improving formal classifications systems that allow

for better access and organization, programming, and collection development

policies that

allow librarians to keep collections relevant and enticing to patrons.

A librarian

looking to begin or expand their library’s collection in graphic novels has a

wide range of potential resources. Information can be found in books like

Serchay’s The Librarian’s Guide to

Graphic Novels for Adults (2010) and Graphic

Novels Now: Building Managing, and Marketing a Dynamic Collection

(Goldsmith, 2005). There are also a host of articles for librarians who serve

different audiences. For example, school librarians can access the articles,

“Graphic novels and school libraries” (Rudiger & Schliesman, 2007) and

“Graphic novels in libraries: Supporting teacher education and librarianship

programs” (Williams & Peterson, 2009) for reference. Collections

specialists could read the article, “Comic books and graphic novels for

libraries: What to buy” (Lavin, 1998) and academic librarians could begin with

“Graphic novels in academic libraries: From Maus to manga and beyond”

(O’English, Matthews, & Lindsay, 2006).

Although there is

a considerable amount of literature for librarians looking for practical

guidance in collecting comic books, there is not as much information on the

overall adoption rate of comic books by public libraries. The most recent

account on the adoption of comics in libraries comes from a survey of

librarians done by the American Library Association’s Office of Intellectual

Freedom in 2005. However, it is not a detailed account or analysis of comics

and graphic novels in libraries. The results were disclosed in a press release

titled, Graphic Novels: Suggestions for

Librarians (2006). Of 185 public library employees surveyed, 97% indicated

comics or graphic novels were in their libraries. However, no information on

the author or methodology behind the study was included. Only the number of

participants and three resulting statistics were included. Efforts to find more

details behind the study were unsuccessful.

Other researchers

have assessed library collection of comic books by measuring the adoption rate

of historically important titles. In a study surveying the holdings of all academic

members of the Association of Research Libraries (Werthmann, 2010), it was

discovered that a wide discrepancy exists regarding the amount of graphic

novels collected. Werthmann based his investigation on a list of 77 comic books

that are highly regarded by critics, and then investigated which libraries had

them as part of their collections. He discovered that most libraries had some

graphic novels, but the amount collected generally correlated with the size of

their collection, and some of the libraries surveyed had none of the titles on

the list.

Research Goals & Objectives:

Comic books and

video games represent two different generations of new media forms entering

libraries. The primary goal of this research study was to assess the

collection, use, and impact of comic books and graphic novels in libraries. The

secondary goal was to study the role of video games in libraries as a point of

comparison for the role of comics in the library, as both media forms have a

similar media history. The central objectives of this research were:

- To assess the frequency with which

American public libraries keep graphic novels as part of their collection

- To assess the frequency with which

American public libraries keep console video games as part of their collection

- To assess the demographics of patrons

who utilize graphic novel and video game collections

- To assess the impact of graphic novel

collections on youth engagement and library promotion

- To assess the shelving decisions

libraries make regarding graphic novels

- To assess the relationship between

graphic novel and console video game collections

Methodology

The

first step was the development of a survey instrument based on research

goals. Input from public library employees was used to frame the questions

in the working context of a public library system. The survey instrument was

hosted publicly on Google Drive, and was tested by a small number of

pre-service librarians in a graduate MLIS program. The responses to the survey

were automatically collected into a database also hosted on Google Drive.

Once

the survey was constructed and tested, a list of public libraries was obtained.

A list of over 9,000 American public libraries and library systems was

retrieved from the US government data clearinghouse (Institute of Library and

Museum Services, 2011). Four hundred and

fifty libraries were selected at random. The government database contains the

web address of each library, and the individual websites of the selected libraries

were used to identify the collections specialist for each library. The request

to participate in the study was then sent by email to the collections

specialist. If no collections specialist or person with a similar role was

identifiable, the request was sent to the e-mail listed for general inquiries.

Somewhat similar research has used Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests

to force libraries into participating in a study on patron challenges

(Musgrave, 2013). In this case it was decided not to use the leverage of FOIA

requests to ensure a completely voluntary participation.

The

requests to participate included an explanation of the purposes of the research

and a link to the survey instrument. Appeals for participation were also made

over public librarian-related social media. To ensure the participants were

from public libraries and had roles within libraries that gave them enough

perspective to answer our survey, participants were asked for their position

title and what kind of library they serve. Survey participants were also told

that they could receive a copy of the final outcome of the survey if they

included their e-mail address, and 85.8% of participants gave their address.

The targeted nature of the appeals for participation and the specific nature of

the professional questions were intended to help to ensure an appropriate

sample. Results from participants who did not indicate they worked in a public

library or did not provide any professional details were removed. The survey

was kept online for two months from the time of the last request for

participation.

Results

At the

end of the surveying period, the final data included responses from 106

participants. Participants represented 31 states, and had an average library

service population of 121,792 users. Participants included libraries that serve

populations as small as 600 users, and as large as 3 million users; the median

size was 16,000 users. Of the 106 participants, 104 indicated they had comics

or graphic novels in their collections and only two indicated they did not.

These results closely mirrored the results of the ALA/Comic Book Legal Defense

Fund study from seven years earlier (National Coalition Against Censorship,

2006). This survey showed

98.1% of respondents had comic books, the earlier ALA/Comic Book Legal Defense

Fund study (2006) found 96.7% did; statistically, this is not considered an

increase.

The

most apparent factor in motivating libraries to add graphic novels was user

demand. Participants were asked in a free-writing format why their library

began adding graphic novels to the collection, and 66.9% of libraries with

comics indicated patron demand as the primary motivating factor. Twelve

participants (11.6%) indicated that collections were started by library staff

with an interest in comics, and nine participants (8.7%) stated that their

libraries purchased comics in an attempt to encourage patronage.

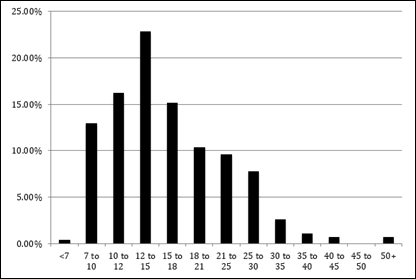

Participants

were presented with age brackets of patrons, and asked which groups most

commonly use comics and graphic novels. As seen in Figure 1, the most commonly

indicated user for library comics and graphic novels was between the ages of 12

and 15 (making up 23% of graphic novel circulation), closely followed by users

aged 10 to 12 (16%) and 15 to 18 (15%). Overall, 52% of graphic novel

circulation could be attributed to people 18 years of age and younger.

Figure

1

Percentage of graphic novel collection circulation by

patron age group.

The results indicated that 29 out of 106 (27.4%)

libraries participating had clubs or events relating to comics. Out of the 29

libraries with comic-themed clubs or events, 6 libraries had both clubs and

events, 9 libraries had a comic book/manga related club but no events, and 14

only had events related to comics. This activity seemed to favor larger

libraries, as the average constituent population size of the libraries that had

comic book activities (195,811) was more than double that of the libraries that

did not host comics-related activities (95,793).

Participants were also asked questions about

collecting console video games within their respective libraries. While not as

prevalent as comic books and graphic novels, this study found a number of

public libraries stocking console video games. Forty-eight out of 106

respondents (45.3%) indicated that they had console games in their library’s

collections. Games for Nintendo’s Wii system were the most common, but games

for Nintendo DS, Microsoft Xbox and other systems were found. Collecting

console video games seemed to be more common in larger libraries, as the

average service population size of the libraries with games was over three

times larger (186,112) than the libraries with no games (53,521). Interestingly,

only a low positive correlation was found between collecting video games and

having comic related clubs and events (Pearson’s r = 0.164). Participants were

asked to rate the popularity of their graphic novel and video game holdings

with users, on a scale of one to five. Comic books were indicated as being more

popular (μ = 3.81) than video games (μ = 3.31).

As mentioned, there has been discussion amongst

librarians around the world about the classification of graphic novels and

comic books (Masuda, 1989). Survey participants were asked where the comic

books and graphic novels were shelved in their library.

- 25.2%

put them in the Young Adult or Children’s section

- 14.5%

placed all comics/graphic novels in a separate section

- 60.1%

had them in multiple areas of the library

While the results showed that only 14.5% of public

libraries put all their graphic novels and comic books into a separate section,

a portion of the librarians who indicated they kept these materials in multiple

sections also indicated that they had a featured area for these materials.

Overall, 23.3% of responding libraries indicated that there was a part of their

shelving that included an area exclusively dedicated to comic books and graphic

novels.

Pro-comics and graphic novel material for librarians

often contains advice for working with comic books as a potentially problematic

material. Of the 106 respondents, 6 indicated that they had policies for

restricting materials based on age, in response to parental request, in their

libraries, and none of these policies had anything particularly to do with

comics or graphic novels.

Summarizing the results in the context of the research

goals and objectives provides a portrait of activity that could potentially be

useful for both librarians and researchers. The results:

- confirmed

that overwhelmingly, American public libraries keep graphic novels as part

of their collection.

- revealed

that less than approximately 40% of American public libraries keep console

video games as part of their collection.

- revealed

that librarians indicated that both comic books/graphic novels and video

games are highly circulated items, but comic book are more popular than

video games.

- indicated

that people under the age of 18 are the primary users of comic books from

the library.

- show

that there are a range of shelving options being used by libraries when it

comes to comic books and graphic novels. The majority of libraries have

them in multiple sections, and almost one in four has some section of

their library specifically dedicated to displaying comic books.

- found

that libraries serving larger communities are more likely to collect video

games and have comic book based clubs. However, there is little

correlation between collecting video games and hosting comic book events.

Discussion

The first comic book debuted in 1934 (Nyberg, 2009),

and the first commercial video game, in 1971 (Emmens, 1982). Thus, at the time

of this writing, comic books are approximately 80 years old, and video games

are just over 40 years old. The results of this study show that comic books and

graphic novels have become a part of library culture, and video games are on

their way to doing the same.

Future research could involve performing database

searches to learn more about the small percentage of libraries that do not

collect comic books or graphic novels. Werthmann (2010) found that, although

rare, there recently were academic research institutions with virtually no

comic books in their libraries. There is the possibility of more public

libraries with no comic books or graphic novels than identified in this study.

Libraries with limited resources may have been less inclined to participate in

our survey, although our results are in line with previous ALA sponsored

research.

A potential next step would be to look at the details

of collection. For example, comic books can be subscribed to as periodicals or

collected as bound volumes. It is not known if libraries collect periodical

comics, and if these are handled differently. Comic books from Japan, known as

Manga, are popular in the comic book genre. It would be interesting to know

what percentage of libraries’ collections nationwide are dedicated to Japanese

comic books, as a measure of globalization of culture. This study found that libraries

collecting console video games was fairly common, but we did not ask if the

libraries also carried and checked out the systems needed to play these games.

Now that library collection of comic books and video games has been

established, more details on the decisions surrounding that collection are

warranted. This study relied on voluntary participation; it only asked library

staff to give broad numerical estimates on the ages of people who check out

comic books and their popularity in circulation. Asking a staff member what

percentage of their comics are Japanese in origin or what video game console is

checked out the most would be better served by a separate study where

libraries’ collection databases are accessed directly.

It is currently a tough climate for many public

libraries; over 40% of states handed budget cuts to public library systems in

the last three years, and 45% of public libraries state that they still don’t

have sufficient internet speeds (ALA, 2012). On the surface, it might seem somewhat

intuitive that larger libraries would be more likely to collect video games due

to larger operating budgets. However, in reality, the retail price of video

games tends to be between $20 USD and $60 USD, meaning that they are not

tremendously more expensive than books. Anecdotally, the two libraries that

stated they did not have comics and graphic novels in their collections each

indicated an average service population size of under 5,000 users. The total

service population of the combined libraries of survey respondents was over

11.9 million. While the results showed

that over 98% of library systems surveyed had comics, the percentage of the

American population that has a local library with comic books or graphic novels

could certainly be higher.

The results could potentially be interesting to

literacy specialists, as more than half of comic book and graphic novel

checkouts are to people under 18 years of age, and these are generally

considered difficult years for male students and reading (Young & Brozo,

2001). The results are also potentially interesting on a commerce level, as the

survey results showed that the demographics of people who check out comics from

the library are substantially different from recent research on the

demographics of the people who purchase comics. DC Comics recently paired with

Nielsen to do a demographic analysis of comic book readers in coordination with

the launch of their comic book line titled The

New 52 (DCE Editorial, 2011). The results showed that less than 2% of their

sales were to people under 18 years of age. In the same study, DC found that

half of their readers were 35 years of age and older, and that their most

active demographic is aged 25-35 years. Comic book companies should understand

that these results indicate that comic books in the library are not a threat to

sales from comic book stores. Further research could specifically investigate

if there is a link between library behaviours and comic purchasing behaviours.

Conclusion

The clear takeaway from this study is that comic books

have become an ingrained part of public library holdings in the United States.

While it is not impossible to find a library with no comic books or graphic

novels, this is now the second study to show that upwards of 97% of public

libraries have them in their collections. Video games, being approximately half

the age of comic books, are still only found in less than half of libraries,

showing that they are far from being fully embraced by libraries as a whole.

The results also show that larger libraries are using graphic novels and comics

for community engagement with a far greater frequency than smaller libraries.

The collection discrepancy is even wider in the adoption of video games.

A public librarian considering resource allocation can

be assured that collecting comics and graphic novels is a widespread library

phenomenon, and that their collection can promote young adult circulation.

Publishers of comic books can also use the results of this study to understand

that libraries collecting comics is a potential pathway to comic book sales

later in life. While the differences between large libraries and small

libraries in the collection and use of graphic novels and video games might

seem troubling on the surface, overall trends show an American Public Library

system that is adapting to changes in patron demand and changes in the overall

media landscape.

References

American Libraries Association. (2012). State of America’s Libraries Report. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/news/mediapresscenter/americaslibraries/soal2012/public-libraries

Annoyed Librarian. (2008). Public librarians: Why do they bother? Journal

of Access Services, 5(4),

611-621.

Brown v. EMA, 564 U.S. (2011). Slip Opinion. Retrieved from http://www.supremecourt.gov/

opinions/10pdf/08-1448.pdf

Buchanan, K. & Vanden Elzen, A. (2012). Beyond a fad: Why video

games should be part of 21st century libraries. Education Libraries, 35, 15-33.

Institute of Library and Museum Services (2011) Public Library Survey

(PLS) 2011. Retrieved from http://catalog.data.gov/dataset/public-library-survey-pls-2011

DCE Editorial. (2012) DC Comics - The New 52 Product Launch Research

Results. Retrieved from http://www.dccomics.com/blog/2012/02/09/dc-comics-the-new-52-product-launch-research-results

Elzen, A. (2012). Beyond a fad: Why video games should be part of 21st

century libraries. Education Libraries, 35, 15-33.

Emmens, C. (1982). The circulation of video games. School Library

Journal, 29(3), 45.

Goldsmith, F. (2005). Graphic

novels now: Building, managing, and marketing a dynamic collection. ALA

Editions. Chicago, IL.

Grossman, L. C. D., & DeGaetano, G. (2009). Stop teaching

our kids to kill: A call to action against TV, movie & video game violence.

Random House LLC. New York.

Grossman, L., & Lacayo, R. (2010). All-TIME 100 Novels.

Originally published January 11, 2010. Retrieved from http://entertainment.time.com/2005/10/16/all-time-100-novels/slide/watchmen-1986-by-alan-moore-dave-gibbons/

Hartman, A. (2010). Creative shelving: Placement in library collections.

In R. G. Weiner (Ed.), Graphic novels and comics in libraries and archives:

Essays on readers, research, history and cataloging (pp. 63-67). Jefferson,

NC: McFarland & Company.

Holston, A. (2010). A librarian’s guide to the history of graphic

novels. In R. G. Weiner (Ed.), Graphic novels and comics in libraries and

archives: Essays on readers, research, history and cataloging (pp. 9-16). Jefferson, NC: McFarland

& Company.

Koop, C. E. (1982, November 9). Surgeon General sees danger in video

games. New York Times, p. A16.

Lavin, M. R. (1998). Comic books and graphic novels for libraries: What

to buy. Serials Review, 24(2), 31-45.

Levine, J. (2009). Gaming, All Grown up. In American Libraries.

August-September, pp. 34-35.

MacDonald, H. (2013, May 3). How graphic novels became the hottest

section in the library. Publishers Weekly,

20-25.

Masuda, C. (1989). Gakko toshokan to manga [School libraries and manga].

Gakko Toshokan, 468, 9-18.

Moore, A., Gibbons, D., & Higgins, J. (2005). Watchmen.

DC comics. New York.

Musgrave, S. (2013). Librarian rebukes nun over comic books. Muckrock, Retrieved from https://www.muckrock.com/news/archives/2013/oct/25/librarian-rebukes-nun-over-comic-books/

National Coalition against Censorship, American Library Association and

Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (2006), “Graphic novels: suggestions for

librarians”, available at: http://www.ncac.org/graphicnovels

(accessed January 31, 2007).

Nyberg, A. (2009) How librarians learned to love the graphic novel. In

R. G.

Weiner (Ed.), Graphic novels and comics in libraries and archives:

Essays on readers, research, history and cataloging (pp. 26-40). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

O'English, L., Matthews, J. G., & Lindsay, E. B. (2006). Graphic

novels in academic libraries: From Maus to manga and beyond. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 32(2),

173-182.

Pyles, C. (2012). It’s no joke: Comics and collection development. Public

Libraries, 51(6), 32-35.

Rudiger, H. M., & Schliesman, M. (2007). Graphic novels and school

libraries. Knowledge Quest, 36(2),

57-59.

Satrapi, M. (2007). The complete Persepolis. New York:

Pantheon Books.

Scott, R. W. (1998). A practicing comic-book librarian surveys his

collection and his craft. Serials Review, 24(1), 49-56.

Segraves, E. (2010). Teen-led revamp. In R. Weiner (Ed.), Graphic

novels and comics in libraries and archives: Essays on readers, research,

history and cataloging (pp. 68-71). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Serchay, D. S. (2010). The

librarian's guide to graphic novels for adults. Neal-Schuman Publishers.

New York.

Sheppard, A. (2007). Graphic novels in the library. Arkansas

Libraries, 64(3), 12-16.

Spiegelman, A. (1995). Maus: A survivor's

tale. PROTEUS, 12(2), 1-2.

Thrasher, F. M. (1949). The comics and delinquency: Cause or

scapegoat. The Journal of Educational Sociology, Vol. 23, No. 4.

195-205.

Thompson, C. (2004). Blankets: An illustrated novel. Top

Shelf.

Tilley, C. L. (May 2008). Reading comics. School Library Media Activities Monthly, 24(9), 23– 26.

Wertham, F. (1954). Seduction of

the innocent: The influence of comic books on today's youth. New York:

Rinehart & Company.

Werthmann, E. J. (2010). Graphic novel holdings in academic libraries:

An analysis of the collections of association of research libraries members. In

R. G. Weiner (Ed.), Graphic novels and

comics in libraries and archives: Essays on readers, research, history and

cataloging (pp. 242-59). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Williams, V. K., & Peterson, D. V. (2009). Graphic novels in

libraries: Supporting teacher education and librarianship programs. Library Resources & Technical Services,

53(3), 166-173.

Young, J. P., & Brozo, W. G. (2001). Boys will be boys, or will

they? Literacy and masculinities. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(3),

316-325.