Feature

EBLIP7 Keynote: What

We Talk About When We Talk About Evidence

Denise Koufogiannakis

Collections and

Acquisitions Coordinator

University of Alberta

Libraries

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Email: denise.koufogiannakis@ualberta.ca

Received: 22 Aug. 2013 Accepted: 17 Oct. 2013

![]() 2013 Koufogiannakis . This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Koufogiannakis . This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

The following text is a summary of the opening keynote address at

the 7th International Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice Conference, given on July 16, 2013 at the University of Saskatchewan,

in Saskatoon, Canada.

Introduction

This morning I want us all to start thinking about evidence! Now I

know that doesn’t seem too revelatory given that we’re at an evidence based

practice conference -- but I think that we don’t usually take the time to think

about what evidence actually is in the profession of librarianship, or how we

use it. So, my talk is going to explore those issues of evidence, based

on the findings from my doctoral research.

What is Evidence?

The Oxford Dictionary says that evidence is: “the available body

of facts or information indicating whether a belief or proposition is true or

valid” (Evidence, 2010).

Looking at the wider body of literature about the nature of

evidence, key elements of evidence are revealed and can be applied to the field

of Library and Information Studies (LIS). In keeping with the previous

definition, evidence is commonly thought of as something constituting a form of

proof to enhance a claim (Hornikx, 2005; Upshur, VanDenKerkhof & Goel,

2001; Reynolds & Reynolds, 2002; Twinning, 2003). That evidence

serves as a proof, differentiates it from information – information must be

relevant to the question at hand, and be used to prove a hypothesis in order to

be considered evidence.

Evidence is generally seen as having three major

properties: relevance, credibility, and inferential force or weight (Schum,

2011). Relevance looks at how the information bears on what is attempted to be

proven; credibility asks whether what is reported actually occurred; and,

inferential force or weight considers how strong the evidence is in comparison

to other evidence.

Types of evidence noted in the literature are wide ranging. Rieke

and Sillars (1984) consider there to be four types of evidence: anecdotal (a

specific instance), statistical (numerical representation of multiple

instances), causal (explanation for the occurrence of effect), and expert

(testimony of an expert) evidence. In a similar vein but considering a

different categorization of evidence, Glasby, Walshe, and Harvey (2007) created

a typology with three types of evidence: theoretical (ideas, concepts and

models to explain how and why something works), empirical (measuring outcomes

and effectiveness via empirical research), and experiential (people’s

experiences with an intervention). They say that “we need to embrace a broad

definition of evidence, which recognises the contribution of different sorts of

knowledge to decision making” (p. 434). Evidence must always be used in

context, whether in the context of a particular situation, or context of a

wider body of professional knowledge.

In my recent PhD research, a grounded theory study, I

studied a group of 19 participants. All were academic librarians in Canada,

working in a variety of settings and positions. They kept online diaries in the

form of a private blog, for the period of one month each, in which they wrote

down the problems or questions that they encountered in their practice during

that time period, and what they did about them. Basically, they were tracking

their thought and decision making processes for me. I then interviewed each

participant to dig deeper into the detail of their decision making, and learn

why they made the decisions they did, as well as what kinds of evidence they

used to help them in making that decision. I wanted to learn about what sources

academic librarians use as evidence and how they use that evidence.

Driving the study was a desire to base the model of

evidence based library and information practice (EBLIP), which promotes the use

of research evidence in practice, on research itself. With the exception of a

study by Thorpe, Partridge and Edwards (2008) (see also Partridge, Edwards and

Thorpe, 2010), no research had been conducted on the actual EBLIP model and

whether it was useful or appropriate for librarians. Since EBLIP was adapted

from evidence based medicine (EBM), it was a legitimate question to ask whether

the same model that worked for physicians really works for librarians. It was

time to explore whether the model was valid and if changes were needed. The

goal was to approach the study with a view to learn and to listen to academic librarians

and how they use evidence in daily practice.

After doing a thorough examination of the model of

EBLIP as it has been presented in the literature, it became clear to me that

“evidence” in the context of EBLIP refers to published research articles.

Booth’s definition, as noted here, does account for other aspects, but the

focus is on research derived evidence, and what we have pursued within the

EBLIP movement since the time of this definition, points mostly to research

evidence:

“an

approach to information science that promotes the collection, interpretation

and integration of valid, important and applicable user-reported, librarian

observed, and research-derived evidence. The best available evidence, moderated

by user needs and preferences, is applied to improve the quality of

professional judgements.”

(Booth, 2000)

The process of EBLIP, as with other forms of evidence based

practice, is one which advocates searching the literature to find research

articles, appraising those research articles to ensure they are valid, and then

integrating the findings into one’s practice. While professional

knowledge and user preferences are accounted for in the definition of EBLIP,

the conversation about those elements stops there. There have also been criticisms

that the EBLIP model does not account for other forms of knowledge that are a

vital part of professional practice. Booth himself has more recently tried to

clarify that EBLIP requires more than research, and that “the best available

evidence and insights derived from working experience, moderated by user needs

and preferences” are essential (Booth, 2012).

The more basic question of “what is evidence?” has not yet been debated

or tested to any degree within the literature of EBLIP. There has been no research

to show that in LIS evidence only consists of research; this treatment of

evidence was simply adapted from the evidence based medicine model.

“I’m Clueless how to Speak

Evidence”

When participants in my study were directly asked what they

considered to be evidence, most were a bit taken aback by the question - often

noting that they had not thought about what evidence was before, or admitting

that it was “a difficult question”. After thinking about it, most participants

took a very broad view of evidence - they were very open to the possibility of

what evidence might be. Most participants named several sources of evidence,

and usually put those in context. For example, different evidence sources

depending upon the type of problem faced.

As for what the participants actually used as evidence - my

research revealed that academic librarians use a wide breadth of evidence

sources in their decision making. Actual evidence sources used were numerous

and detailed. In order to best convey this information, the evidence sources

have been grouped into two main types, and within those types there are a total

of nine main categories of evidence (Koufogiannakis, 2012).

Hard evidence sources are types of evidence that are usually more

scientific in nature. They may focus on numbers, or are tied to traditional

publishing outputs. Sources are usually quantitative in nature, although

qualitative research and non-research publications also fall into this

category. Ultimately, there is some written, concrete information tied to this

type of evidence. A librarian can point to it and easily share it with

colleagues. It is often vetted through an outside body (publisher or

institution), and adheres to some set of rules. These types of evidence include

the published literature (research and non-research articles), facts,

documents, statistics and data, as well as local research and evaluation

projects that are documented. These sources are generally acknowledged as

acceptable sources of evidence, and are what a librarian would normally think

of as evidence in library and information studies.

The other type of evidence can be thought of as “soft” evidence.

As opposed to the “hard” evidence, soft sources of evidence are non-scientific.

They focus on experience and accumulated knowledge, opinion, instinct, and what

other libraries or librarians do. This type of evidence focuses on a story, and

how details fit into a particular context. Soft evidence provides a real-life

connection, insights, new ideas, and inspiration. Such types of evidence

include input from colleagues, tacit knowledge, individual feedback from users,

and anecdotal evidence. These types of evidence are more informal and generally

not seen as deserving of the label evidence, although they are used by academic

librarians in their decision making as a form of proof.

I want to illustrate this use of multiple types of evidence through

the example of information literacy. Let’s just pretend that librarians at a

University need to develop a new information literacy program for engineering

students. What are the evidence sources they are likely to draw upon (in broad

terms, without knowing the specific context)? This is to illustrate how we go

about gathering evidence, and where we find it.

First the librarian might reflect on his or her own past knowledge

or experience in teaching information literacy skills to reflect upon what has

worked for him or her in the past. He or she will likely speak with colleagues

at their own institution to learn what has worked in other subjects or courses.

The librarian may then speak with faculty – looking to discover what students

in this course need to learn; what are the course objectives?

They may then branch out to see whether any other universities

offer a similar course; start looking at the literature for examples of what

worked elsewhere; look on the internet at other Universities’ websites for

documentation or other types of information relating to such a course. Then

they may decide to follow up that initial investigation of what others are

doing by arranging to speak with specific librarians at other universities and

learn what they did and what was successful. At the same time, they may probe

deeper into the literature to look for any research studies that show what is

most effective. In addition, they may look at documents such as the ACRL (2011)

information literacy guidelines, for guidance.

The librarian will then go back to local information

- is there any internal data or research on information literacy or student

needs? What needs to be evaluated once the course starts? The librarian may

begin planning evaluation and feedback mechanisms, and may even think about

whether there is a research project they can carry out within this new

endeavour.

Ultimately, the librarian must make a decision on how to teach the

course. Which of the sources consulted might be best to help with that decision?

It’s complicated! Which do we place more weight in? Which should we place more

weight in? How do we know what is best? How do we combine the various pieces of

what we learn through the evidence gathering process? This is still a very big

gap in our knowledge, and should be of utmost importance to those of us

interested in evidence based library and information practice.

What I’ve learned about evidence in LIS, is that it can come from many sources. Evidence

is much more than research – and depending upon the type of question or problem

we are trying to address, research will not always be the best source of

evidence. The role of EBLIP is about

using evidence and figuring out what is the best evidence in your particular

situation. Evidence use is not easily prescriptive, and must consider

local circumstances.

EBLIP’s focus to date has

been on research evidence and how to

read and understand research better. This is a good thing (I certainly do not

want to diminish the importance of the work that has been done in this respect)

- but it is not the only thing - and we must begin to explore other types of

evidence.

And finally, I think that librarians would be better

served by a having greater understanding of the best types of evidence to use

in particular situations. The question, then, is how do we best weigh different

sources of evidence? I do not yet have that answer, nor has it been explored in

our research literature to date.

How do Librarians Use Evidence?

I now want to turn our thoughts to how we, as librarians, use evidence.

As previously mentioned, the focus of EBLIP to date

has been on research evidence, and when we look at the model of EBLIP, which

was adopted from medicine, it is clearly targeted toward the individual

practitioner.

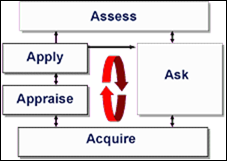

This figure illustrates the 5A’s you are likely all

familiar with - it outlines the process of Evidence Based Practice, and is what

we have adopted within EBLIP.

Figure

1

The

5A’s process of evidence based practice (Hayward, 2007).

This

model is meant to be used by an individual practitioner - a physician, nurse,

and in our case, librarian. The librarian works through each of these steps to

practice in a more evidence based way.

The findings from my doctoral study illustrated one very basic but game-changing

thing to me - that academic librarians (and I think this is largely

transferable to other types of librarians) work in groups. All of our major

decisions are made in groups, or require approval from others. There are some

smaller decisions that we make on our own, but for the most part, our

professional decisions rely upon others.

Now,

maybe some of you at this point are saying, “well, yeah, of course” but even

though I have been an academic librarian for more than 15 years, and have been

involved with the EBLIP movement for more than 13 years, this was a complete

revelation to me. The fact is that our work in groups changes how we make

decisions as opposed to when we make decisions on our own; and the fact is also

that we make more decisions in groups than we do as individuals. This must have an enormous impact on the

discourse within EBLIP, because if we want evidence to truly permeate and

improve librarian decision making, we need to look at EBLIP from the context of

group decision making.

This leads me then to how we actually use evidence, which has not been very

well explored through research prior to my study. We use evidence for

convincing, and I will explain this in more detail. There are two main aspects

to convincing (Koufogiannakis, 2013a, 2013b).

First

of all, evidence is used for confirming. My research found that one of the main

reasons librarians use evidence is to confirm that the decision they are making

is correct. Confirming generally applies in situations where an individual decision

is being made, or when the librarian is part of a well-functioning group that

she or he feels comfortable with.

Confirming

is nearly always positive because in doing so, a librarian is seeking to better

understand something and add to their knowledge as a professional. What emerged

very clearly in the data from participants is that academic librarians confirm

to feel better and more confident that they are doing the right thing while

remaining open to new possibilities. They may have initial thoughts, reactions

and instincts, but they want to confirm those instincts with more concrete

sources of evidence in order to proceed with their decision in a more confident

manner. This is another way that the librarian brings together the soft

evidence of their initial gut instinct or their own knowledge, with harder

sources of evidence that corroborate the soft evidence, or else make the

librarian re-think their initial position on the matter due to new evidence

that was not previously known or considered.

The quotes below, from participants in my study, illustrate some of the reasons

and ways that librarians use evidence to confirm. Participants felt that they

could not base decisions solely on their existing knowledge because best

practices are constantly changing and they need to continually learn. From

those librarians just starting out, to those that were quite experienced, there

was a common feeling throughout that they did not know everything and wanted

some form of reinforcement whether it be from the literature, input from

colleagues, or some other source of evidence.

I tend to use that [the

literature] as confirmation for interesting ideas that I read about. (Librarian

16, interview)

I find it interesting when the outcome

matches/supports my initial gut reaction and instincts. For me this is one of

the ways I test for validity when making decisions, a little private “ah-ha”

moment – I can say, with confidence: ‘I knew it, I knew I was right’. If the

info collected informs a decision or action different from my initial thought –

I chalk it up to experience and put it under the category of: ‘good thing I

double checked this’. (Librarian 6, diary)

I just think that way and I feel more confident

about what we’re doing if I know that we have – that we’ve tried to collect

evidence, we’ve tried to assess what we’re doing and to me it’s just more

confidence in going forward with other things. (Librarian 17,

interview)

Confirming is done for oneself. It is an act that reassures, and corroborates

instinct or tacit knowledge. The participants’ actions show that they do not

just gather evidence for external purposes, but that they gather and use

evidence as part of their own professional development and regular practice of

keeping current.

Although

not usually the case, confirming can occasionally be negative, if a librarian

consciously discredits or avoids evidence that does not support their

preconceived notion of what is the best.

Secondly,

evidence is used for influencing. As previously mentioned, while some decision

making by librarians is individual, often decisions are made in a group

setting, especially when they will have a major impact on library users or

staff. My research shows that group decision making leads librarians to try and

influence the final decision. Influencing can be positive or negative. When in

a positive work environment, participants often first go through the confirming

stage for themselves, but when working with others, they bring evidence to the

table in order to enable the group to make the best decision possible. In a

positive situation individuals feel free to speak and be heard, and will reach

a consensus. What an individual brings to the table, in this environment, is a

positive form of influencing.

When participants were in a negative environment, they often felt they were not

being listened to, or their concerns not heard. They then adopted strategies to

deal with this. One such strategy was to bring research evidence to the table

in support of their viewpoint, where someone with an opposing viewpoint may not

have done this. Research is generally well regarded in an academic environment

and therefore cannot be as easily dismissed as a person's own opinion. Any form

of evidence that shows “what other libraries do” is also seen in a very

favourable light, as libraries may be more likely to make changes based on what

is happening around them at other institutions. Other strategies were to

convince individuals and bring them on-side prior to any decision, or to stress

particular points depending upon what the decision maker needs to hear in order

to be persuaded. In all cases, the individuals want to influence the final

result, and where a work environment is negative, they will use evidence as a

“weapon”, to quote Thorpe, Partridge and Edwards (2008) as they describe in the

findings of their research regarding librarians’ experiences of evidence based

practice, which is in keeping with my findings.

Different levels of control regarding decision making emerged from the data in

this study. It became clear that librarians do not always have control over

their own decisions. When an individual librarian makes his or her own

decision, influencing is not required. In situations where a group makes the

final decision, or where someone else makes the final decision, influencing is

widely used. And the following quotes from participants illustrate the use of

evidence for influencing:

Where the group setting makes a difference, I

think, is that depending upon whether or not I’m a champion for a particular

project, I may present, you know - I may frame the evidence in a way that I

think would speak to the needs of the people in the group. (Librarian

2, interview)

I will have to sell this to the University

Librarian. (Librarian 18, diary)

I think you have to be very strategic because you

have to recognize what the other person’s concerns are in order to address them

and that’s the strategic part; and also being able to address the mandates of

the library and all those other conflicts, right? (Librarian 5,

interview)

The overall concept of convincing

includes the two sub-categories I just discussed, confirming and influencing.

Confirming focuses on the self. It concerns a librarian’s knowledge and

positioning as a professional. In this case, librarians look to the evidence in

order to confirm and reassure themselves that they are on the right track with

their decision making. They turn to the literature or to input from colleagues

in order to verify their initial instincts. This process is a positive one

because it is self-inflicted and builds confidence. Generally, the librarian

comes to the process of looking for and using evidence to confirm in a very

open minded and forthright manner.

Influencing focuses on others and what a librarian needs to do to

contribute to what would be a positive outcome from their perspective.

Influencing concerns transmitting what an individual thinks the decision should

be to others that are involved in making the final decision, in order to

convince them to come to the same conclusion. Influencing can be a positive or

negative experience depending upon the work environment. Evidence in this

situation can become simply a means to an end, and used differently depending

upon the circumstances and the people involved.

Work environment largely determines the convincing strategy. For example, in

co-worker relationships, how much control one holds, what is likely to convince

someone, past experiences in dealing with particular people, and the perception

of being heard in the workplace are all factors that impact the use of evidence

and the reasons for using evidence.

Depending

upon the work environment, evidence is used differently. If it is a positive

work environment, academic librarians are more forthcoming with ideas, listen

to others, and are open to what the evidence says. If the work environment is

negative, there is often secrecy, a withholding of information, evidence is

used selectively to make a case, situations are approached differently

depending upon personalities, there are feelings of hopelessness, and

power-plays and strategizing are common.

Generally,

librarians want to contribute to organizational decision making, but if they

feel that they are not being listened to, they will be disempowered and look

for other ways to influence the outcome (or some may simply give up).

Ultimately, individual academic librarians are not in control of most final

decisions. Therefore, they do what they can to influence and impact the

decision indirectly. Our workplaces have a huge impact on how we use

evidence.

Shifting the

EBLIP Paradigm

This

research has shown me that two key parts of the current EBLIP model need to be

reworked.

1)

We need to look at a wider breadth of evidence sources within EBLIP, and move

our discussions beyond research. Librarians use many forms of evidence. This is

legitimate and the EBLIP movement needs to catch up.

2)

We need to consider how librarians do their work, and reframe the model so that

it makes sense within our institutional, group-driven decision making, as

opposed to independent, individual decision making.

I propose to you the following points:

1)

We are not health care professionals:

sources of evidence in health do not necessarily transfer into sources of

evidence in librarianship. It is time to look at ourselves rather than model

another profession.

2)

We have unique types of evidence within

our profession.

3)

We rarely act alone – we work in institutions and make decisions in groups.

4)

We almost always act locally.

5)

We care about what we do and want to influence outcomes.

6)

We don't know enough about ourselves as decision makers.

7)

We don't know enough about what are the most important evidence sources to help

us.

Keeping

these points in mind, I want to propose we start to follow a new model of EBLIP

- which is not radically different, but which suits us better.

In

2009, Booth proposed a new 5As of EBLIP which focus more on collaboration. This

model is a better representation of the EBLIP process as it applies to

librarians and fits very well with what I found in my study. It accounts for

multiple sources of evidence; focuses on group decision making; and places

evidence within the overarching problem and environment. It also encourages

consensus building and adaptation as part of a cyclical process towards

successful implementation, and gives more consideration to the areas of apply

and assess, in the newly named ‘agree’ and ‘adapt’ stages. This version of the

5As is more holistic and encompassing of the complex process of evidence based

decision making, as well as more practical. Booth himself noted that his model

was a work in progress; a prototype which had potential to be modified.

My

doctoral study results fit very well with this model for EBLIP. In my thesis I

build upon Booth’s work to enhance this model further. Booth had based his new

model on threads of discussions happening at the EBLIP5 conference in

Stockholm. While not research, it arose from keen insightfulness of the

discussions within a community of practice. My research has now confirmed that

this model is a better fit for librarians that the original model.

In

addition to Booth’s alternative model, work I previously published, based on a

presentation at the EBLIP6 conference which grew out of an earlier phase of

this study, is drawn upon for the new model (Koufogiannakis, 2011). This work

focuses on questions that a practitioner should ask themselves when making

professional decisions in an evidence based manner. These questions account for

both hard and soft sources of evidence, with a focus on continually asking

questions and improving practice.

My work combines well with that of Booth’s to create a more holistic approach

to practicing librarianship in an evidence based way. A key point however, is that we shouldn’t

focus on the model - we need to do what works. A model itself can serve as a

guide but should be flexible.

This

then is a new model for evidence based library and information practice:

1)

Articulate –

come to an understanding of the problem and articulate it.

Questions:

What do I/we already know about this problem? Clarify existing knowledge and be

honest about assumptions or difficulties that may be obstacles. This may

involve sharing background documents, having an honest discussion, and

determining priorities. Consider the urgency of the situation, financial

constraints, and goals.

Actions:

Set boundaries and clearly articulate the problem that requires a decision.

2)

Assemble –

assemble evidence from multiple sources that are most appropriate to the

problem at hand.

Questions:

What types of evidence would be best to help solve this problem? What does the

literature say? What do those who will be impacted say? What information and

data do we have locally? Do colleagues at other institutions have similar

experiences they can share? What is the most important evidence to obtain in

light of the problem previously articulated?

Actions:

Gather evidence from appropriate sources.

3)

Assess –

place the evidence against all components of the wider overarching problem.

Assess the evidence for its quantity and quality.

Questions:

Of the evidence assembled, what pieces of evidence hold the most weight? Why?

What evidence seems to be most trustworthy and valid? What evidence is most

applicable to the current problem? What parts of this evidence can be applied

to my context?

Actions:

Evaluate and weigh evidence sources. Determine what the evidence says as a

whole.

4)

Agree –

determine the best way forward and if working with a group, try to achieve

consensus based on the evidence and organisational goals.

Questions:

Have I/we looked at all the evidence openly and without prejudice? What is the

best decision based on everything we know from the problem, the context, and

the evidence? Have we considered all reasonable alternatives? How will this

decision impact library users? Is the decision in keeping with our

organisation’s goals and values? Can I explain this decision with confidence?

What questions still remain?

Actions:

Determine a course of action and begin implementation of the decision.

5)

Adapt

–revisit goals and needs. Reflect on the success of the implementation.

Questions:

Now that we have begun to implement the decision, what is working? What isn’t?

What else needs to be done? Are there new questions or problems arising?

Action:

Evaluate the decision and how it has worked in practice. Reflect on your role

and actions. Discuss the situation with others and determine any changes

required.

A

model for EBLIP needs to look at all evidence, including evidence driven by

practice as well as research. Librarians need to take a different view of how

evidence may be used in practice, and tie research and practice together rather

than separating them. Practitioners bring evidence to the table through the

very action of their practice. The local context of the practitioner is the

key, and research cannot just be simply handed over for a practitioner to implement.

The practitioner can use such research to inform themselves, but other

components are also important. Concepts related to practice theory, focusing on

the practitioner and his or her knowing in practice – both local evidence and

professional knowledge – help to provide a more complete picture of decision

making within the profession of librarianship.

The

EBLIP model must be revised so that the overall approach addresses other

aspects of evidence. All forms of evidence need to be respected and the LIS professional,

with his or her underlying knowledge (a part of soft evidence), is at the

centre of the decision making process. Different types of evidence need to be

weighed within the context in which they are found, and only the practitioners

dealing with that decision can appropriately assign value and importance within

that context.

There

must be an emphasis on applicability, because decision making is ultimately a

local endeavour. In every situation, we must work within restrictions. These

elements are facts of life and cannot be ignored. Within such boundaries

librarians need to weigh appropriate evidence and make contextual decisions.

An evidence based library and information practitioner is someone who

undertakes considered incorporation of available evidence when making a

decision. An evidence based practitioner incorporates research evidence, local

sources of data, and professional knowledge into their decision making.

All three must be present.

Moving Forward

There

are two large areas of research I would like to see the EBLIP community address

in the next few years:

1. What are

the best evidence sources based on the type of question? It

would be beneficial for researchers to explore and recommend the best evidence

sources based on the type of question. This would not be a hierarchical list,

but would serve as a guideline on what sources of evidence a librarian should

consult for that type of question. For example, if one has a collections

problem, the research literature should be consulted, but other sources of

evidence that would provide good information include usage statistics for

e-products, circulation statistics, faculty priorities, output of tools such as

OCLC collection analysis, interlibrary loan and link resolver reports, as well

as the publication patterns of faculty. Researchers could determine what the

sources are for each area of practice, and in what circumstances they are best

used.

2. How do we

“read” the results of different types of evidence sources? It

would also be very beneficial for practitioners to have guidance on how to

“read” the results of different evidence sources. For example, what a

practitioner needs to consider when looking at reference statistics, or what

elements a librarian should consider when conducting an evaluation of their

teaching. Some of this information will be found in existing literature, and a

scoping review of what has already been documented would be a good start. We

have already done this with the development of critical appraisal tools for

research studies and it would be beneficial to extend this work to other types

of evidence sources.

Evidence Helps

us Find Answers

To

close, I’d like to encourage you all to keep thinking about evidence and how

you use it. Ultimately, evidence, in its many forms, helps us find answers.

However, we can’t just accept evidence at face value. We need to better

understand evidence - otherwise we don’t really know what ‘proof’ the various

pieces of evidence provide. EBLIP has already made great strides towards better

understanding research evidence, and while we need to continue to improve our

research literature, we also need to extend that effort towards understanding

other types of evidence that is used in librarianship.

I

think we can only do this if we question, test and allow ourselves and one

another to make mistakes while learning and exploring.

What

excites me about all this is very much in keeping with the theme of this

conference – “The possibilities are endless”. There are endless questions,

endless ideas, and we all have something to contribute. In fact, we all

need to contribute. Above all, EBLIP is a mindset - a way of approaching

practice with openness and curiosity - take time during this conference to

listen, be inspired and discover your

possibilities.

References

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2011). Guidelines for Instruction Programs in

Academic Libraries. Retrieved

6 November 2013 from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/guidelinesinstruction

Booth, A.

(2000, July). Librarian heal thyself: Evidence based librarianship, useful,

practical, desirable? 8th International Congress on Medical Librarianship,

London, UK.

Booth, A.

(2009). EBLIP five-point-zero: Towards a collaborative model of evidence-based

practice. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(4), 341-344. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00867.x

Booth, A.

(2012). Evidence based library and information practice: Harnessing

professional passions to the power of research. New Zealand Library & Information Management Journal, 52(4). http://www.lianza.org.nz/resources/lianza-publications/nzlimj/evidence-based-library-and-information-practice-harnessing-prof

Evidence.

(2013). In Oxford Dictionaries Pro. Retrieved 6 Nov. 2013 from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/evidence?q=evidence

Glasby, J.,

Walshe, K., & Harvey, G. (2007). Making evidence fit for purpose in

decision making: A case study of the hospital discharge of older people. Evidence & Policy, 3(3), 425-437.

doi: 10.1332/174426407781738065

Hayward, R. S.

(2007). Evidence-based information cycle. Centre for Health Evidence.

Retrieved 8 Nov. 2013 from http://www.cche.net/info.asp

Hornikx, J.

(2005). A review of experimental research on the relative persuasiveness of

anecdotal, statistical, causal, and expert evidence. Studies in Communication Sciences, 5(1), 205-216.

Koufogiannakis,

D. (2011). Considering the place of practice-based evidence within evidence

based library and information practice (EBLIP). Library & Information

Research, 35(111), 41-58. Retrieved 8 Nov. 2013 from http://www.lirgjournal.org.uk/lir/ojs/index.php/lir/article/view/486/527

Koufogiannakis,

D. (2012). Academic librarians’ conception and use of evidence sources in

practice. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 7(4), 5-24.

Retrieved 8 Nov. 2013 from http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP/article/view/18072/14468

Koufogiannakis,

D. (2013a). Academic librarians use evidence for convincing: A qualitative

study. SAGE Open, 3(April-June).

doi: 10.1177/2158244013490708

Koufogiannakis,

D. A. (2013b). How academic librarians use evidence in their decision making:

Reconsidering the evidence based practice model. (Unpublished doctoral

dissertation). Aberystwyth University, Wales, U.K.

Partridge, H.,

Edwards, S., & Thorpe, C. (2010). Evidence-based practice: Information

professionals’ experience of information literacy in the workplace. In A.

Lloyd, & S. Talja (Eds.). Practising information literacy: Bringing

theories of learning, practice and information literacy together. Wagga

Wagga, NSW: Charles Sturt University.

Reynolds, R.

A., & Reynolds, J. L. (2002). Evidence. In J. P. Dillard, & M. Pfau

(Eds.). The persuasion handbook:

Developments in theory and practice. (pp. 427-444)

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rieke, R.,

& Sillars, M. O. (1984). Argumentation

and the decision making process. New York: Harper Collins.

Schum, D. (2011).

Classifying forms and combinations of evidence: Necessary in a science of

evidence. In P. Dawid, W. Twining, & M. Vasilaki (Eds.). Evidence,

inference and enquiry. (pp. 11-36). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thorpe, C.,

Partridge, H., & Edwards, S. L. (2008). Are library and information

professionals ready for evidence based practice? Paper presented at the

ALIA Biennial Conference: Dreaming 08, Alice Springs, NT, Australia. Retrieved

8 Nov. 2013 from http://conferences.alia.org.au/alia2008/papers/pdfs/309.pdf

Twinning, W.

(2003). Evidence as a multi-disciplinary subject. Law, Probability & Risk, 2(2), 91-107. doi: 10.1093/lpr/2.2.91

Upshur, R. E.,

VanDenKerkhof, E. G., & Goel, V. (2001). Meaning and measurement: An

inclusive model of evidence in health care. Journal

of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 7(2), 91-96. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2753.2001.00279.x