Conference Paper

Value

of Libraries: Relationships Between Provision, Usage, and Research Outcomes

Michael Jubb

Director

Research Information Network

London, England, United Kingdom

Email: michael.jubb@researchinfonet.org

Ian Rowlands

Research Services Manager and Bibliometrician

University of Leicester

Leicester, England, United Kingdom

Email: ir46@le.ac.uk

David Nicholas

Director

CIBER Research Ltd

Newbury, England, United Kingdom

Email: Dave.Nicholas@ciber-research.eu

![]() 2013 Jubb, Rowlands, and Nicholas. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Jubb, Rowlands, and Nicholas. This is an

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objective – To explore the relationships in the United

Kingdom between library expenditures, levels of usage, and research outcomes,

focusing on the provision and use of e-journals.

Methods

– The project used a mixture of top-down and

bottom-up approaches. It involved a close study of the behaviors of researchers

in eight universities and two research institutes across a range of six subject

areas, along with a parallel gathering and analysis of data for all U.K.

universities and colleges, covering various library indicators together with

data on article downloads and a range of measures of research performance. The

work was undertaken in two stages and was completed in 2010. The first stage involved

detailed mining of the publishers’ logs from Elsevier’s Science Direct and from

Oxford Journals to generate fine-grained insights into the information-seeking

behavior of scholars from the case study institutions, together with an initial

analysis of the U.K.-wide data. The second stage involved a survey and

interviews with a wide range of researchers as well as librarians from the case

study institutions, together with further analysis of the U.K.-wide data.

Results

– Strong variations were found between users, not

only in different disciplines but also in different institutions. Some, but not

all, of the variations seemed to be related to the size and research intensity

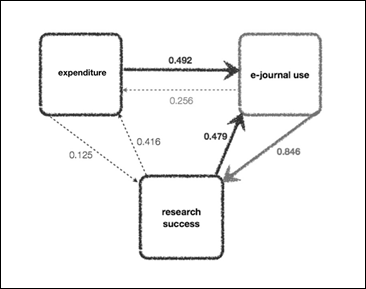

of the institution. Analyses of the U.K.-wide data show that levels of library

expenditure influence subsequent levels of use of e-journals. While the

modeling does not show strong direct linkages in either direction between

library expenditure and research performance, it does show a strong positive

feedback loop between the use of e-journals and research performance.

Conclusion

–

There is a need both to broaden the focus beyond e-journals and for more

detailed work to test hypotheses and understand the dynamics of the

relationships between different variables over time.

Introduction

Expenditure in university and college libraries in

the UK amounted in 2008 to £630 million (Society of College, National and

University Libraries, 2009), a figure that had grown by 30% in real terms over

the previous ten years. Growth in expenditure was even faster – at nearly 48%

– for the libraries of the research-intensive

universities represented by Research Libraries UK (RLUK). Numbers of staff and

students also grew, however, and income and expenditure on research grew even

faster. Hence the proportion of total university expenditure that went to

support libraries fell: from 3.4% to 2.8% across all UK universities; and from

3.2% to 2.6% across the RLUK libraries. So libraries represent a declining

share of university budgets, and they will have to fight hard to avoid further

falls in that share as universities face significant cuts in the income they

receive from public funds.

In that context, it is particularly important that

libraries should be able to show not only that they are operating efficiently,

but that they provide services with demonstrable links to success in achieving

institutional goals. Return on investment is thus an increasingly important

issue. In order to address these issues, libraries need to do more to

understand user behaviour and workflows; and to rigorously analyse and

demonstrate the value of what they do in terms of improving students’

experience, and supporting teaching, learning, and research.

There has been a tendency, in the UK at least, for

performance indicators to focus on inputs and outputs that are relatively

straightforward to measure, as distinct from the much harder issues relating to

impact and value. In current circumstances, however, it is important that more

is done to analyse the relationships between library activities on the one

hand, and learning and research outcomes on the other.

Work of this kind is in its relatively early

stages, and it is fraught with difficulties. Gathering and analysing evidence

of value is notoriously difficult; a number of different approaches have been

adopted, and there is no single answer. A key question is “value for whom?” In

relation to libraries, approaches to gathering evidence of value for students

or academic staff may well differ from approaches to value for funders or for

universities. Similarly, approaches to the value of existing services may not

be appropriate in gathering evidence of possible changes (positive or negative)

either to the nature or to the level of those services. And there are notorious

difficulties in assessing changes in value over time.

This paper focuses on one element in that set of

issues: the provision of information content, particularly e-journals, that

libraries make from within their budgets, and the use that is made of that

content. It reports in particular on the findings of a study commissioned and

overseen by the Research Information Network (RIN), and undertaken by the

Centre for Information Behaviour and the Evaluation of Research (CIBER) at

University College London. The study was undertaken in two stages, and was

completed in 2010.

Project design and methodology

The study started with the aim of providing a

detailed portrait of the information-seeking behaviour of UK researchers, of

how they make use of e-journals and of the benefits that flow from that use.

More detailed objectives were to

·

investigate

researchers’ behaviour, in terms of levels and patterns of usage, content

viewed, navigational preferences, and routes used to access e-journal content

·

ascertain

how researchers’ behaviours vary by subjects and disciplines, and in relation

to the universities and other institutions in which they work

·

gather and

analyse any evidence of relationships between researchers’ behaviours and

usage, and institutional expenditure on e-journals, and

·

gather and analyse any

evidence of relationships between researchers’ behaviours on the one hand and

research productivity, outputs and outcomes on the other, including such measures

as numbers of publications produced, citations attracted, and the results of

research evaluations.

The project used a mixture of top-down and

bottom-up approaches. It thus involved a close study of the behaviours of

researchers in eight universities and two research institutes across a range of

six subject areas; and a parallel gathering and analysis of data for all UK

universities and colleges, covering various library indicators together with

data on article downloads and a range of measures of research performance. The

work was undertaken in two stages. The first stage involved detailed mining of

the publishers’ logs from Elsevier’s Science Direct and from Oxford Journals to

generate fine-grained insights into the information-seeking behaviour of

scholars from the case study institutions, together with an initial analysis of

the U.K.-wide data (Research Information Network, 2009) The second stage

involved a survey and interviews with a wide range of researchers as well as

librarians from the case study institutions, together with further analysis of

the U.K.-wide data (Research Information Network, 2011).

Expenditure and usage of e-journals

Expenditure on information content of all kinds

represents about 35% of all library expenditure across the U.K. university

library sector (Figure 1), and that proportion has been relatively stable over

the past decade. But there are significant differences between individual

libraries – proportions vary between under 30% and over 40% – and

groups of libraries. The proportion tends to be lowest in small colleges and

specialist institutions, and highest in the older universities.

The

relatively stable proportion of expenditure on content implies, of course,

increases in actual expenditure in real terms. But here experiences differ

across the sector. In the research-intensive universities expenditure rose by

52%; but in the newer universities, after rising by 5% in the years up to 2002,

expenditure on content has actually declined in real terms since then, and in 2008

was actually 2% lower than it was in 1998.

Figure

1

Expenditure on information provision as a percentage

of overall library expenditure 1998-2008

The

lion’s share of that expenditure goes to serials, which now account for nearly

20% of total library expenditure across the U.K. higher education (HE) sector.

That marks a significant change over the past ten years. In 1998 books

accounted for just over 12% of library expenditure, and serials just over 15%;

but by 2008 the percentages had diverged rapidly, to 9% and 19% respectively

(Figure 2). In several older universities, serials account for over a quarter

of the total library budget.

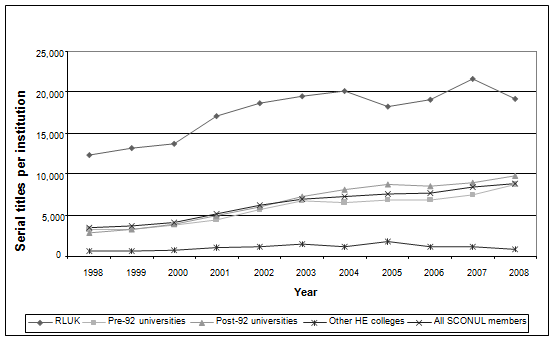

Growth

in expenditure on serials has of course been accompanied, as a result of the

adoption of big deals, by a huge increase in the number of titles available

(Figure 3). Overall, the number of titles has increased by over 153% across all

UK university libraries between 1998 and 2008. Within this, there is

considerable variation, both in the rate of change and in the overall number of

titles available. RLUK members, while showing one of the smaller overall

increases at 56%, has a consistently larger number of titles available than any

other group. Other HE colleges, also showing a lower rate of change at 39%,

have noticeably fewer titles available than pre- and post-92 universities.

Nonetheless, the overall story is one of rapid and significant change.

And

the increase in provision has been accompanied by huge increases in usage. Our

estimates of the number of downloads of e-journal articles as reported by

libraries in accordance with the COUNTER protocols are shown in Table 1. They

show an increase of over two and a half times across

the sector as a whole between 2004 and 2008, with even higher rates of growth

among the research-intensive Russell Group of universities.

One

simple approach to value is to ascertain the unit cost per download and its

variation between different institutions or over time. As shown in Table 2,

since the rise in usage has been faster than the rise in expenditure on

serials, the cost per download fell sharply between 2004 and 2008: from £1.19

to £0.70 (thus by 41%) across the sector as a whole, with an even sharper fall

of 62% among the research-intensive Russell Group universities.

Figure

2

Serials expenditure as a percentage of overall

library expenditure 1998-2008

Figure

3

Number

of serial titles per institution 1998-2008

When

levels of usage are put alongside expenditure on e-journals in individual universities

across the UK, again the results are intriguing. They show a very strong

correlation between volumes of downloads and expenditure, with only a few

outliers; as shown in Figure 4, a matrix

scatterplot based on downloads for all downloads (COUNTER (adjusted), Elsevier

ScienceDirect, and Oxford Journals (fitted linear regression trendlines with 95% confidence intervals). Only the plots

for Oxford Journals show a wide scatter, reflecting the relatively small number

of journal titles involved, and their concentration in a relatively small range

of subject areas. Overall, however, our findings seem to indicate that

universities as a whole are spending their money wisely.

Variations

between subjects and institutions

It

is well known that there are significant variations between the usage

behaviours of researchers in different disciplines, as well as in the provision

of information resources and services directed towards them. This is borne out

by the detailed analysis of the usage logs for Science Direct and Oxford

Journals in our case study subjects and institutions. Table 3 shows that

economists differ from both life scientists and physical scientists in the

degree of concentration on a small number of titles, in the numbers of pages

viewed per session, in their use of abstracts, and in their use of external

gateways such as Google or Google Scholar to get to content.

Table

1

Annual

COUNTER Downloads (CIBER Estimates Based on SCONUL)

|

Mean for sector (Huber’s

M-estimator) |

|||||

|

Year |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

|

Russell

Group |

783,870 |

1,377,603 |

1,846,121 |

2,211,245 |

2,795,825 |

|

Pre-1992

Institutions |

439,813 |

632,144 |

655,926 |

819,335 |

1,001,521 |

|

Post-1992

Institutions |

283,760 |

332,251 |

443,027 |

521,350 |

592,253 |

|

Total |

432,693 |

632,758 |

772,600 |

930,415 |

1,134,165 |

|

|

Index 2004=100 |

||||

|

Year |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

|

Russell

Group |

100 |

175.7 |

235.5 |

282.1 |

356.7 |

|

Pre-1992

Institutions |

100 |

143.7 |

151.4 |

186.3 |

227.7 |

|

Post-1992

Institutions |

100 |

117.1 |

156.1 |

183.7 |

208.7 |

|

Total |

100 |

146.2 |

178.6 |

215.0 |

262.1 |

Table

2

Direct

Cost Per Download at Constant Prices (SCONUL/COUNTER/CIBER Estimates)

|

Mean for sector (Huber’s

M-estimator) |

Index 2004=100 |

|||||||||

|

Year |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

|

Russell

Group |

£1.73 |

£0.99 |

£0.82 |

£0.74 |

£0.66 |

100

|

57.2 |

47.4 |

42.8 |

38.2 |

|

Pre-1992

Institutions |

£1.20 |

£0.96 |

£0.98 |

£0.91 |

£0.81 |

100 |

80.0 |

81.7 |

75.8 |

67.5 |

|

Post-1992

Institutions |

£1.01 |

£0.85 |

£0.73 |

£0.68 |

£0.65 |

100 |

84.2 |

72.3 |

67.3 |

64.4 |

|

Total |

£1.19 |

£0.91 |

£0.83 |

£0.77 |

£0.70 |

100 |

76.5 |

69.7 |

64.7 |

58.8 |

But

there are significant variations also between different areas of the sciences.

In physics and chemistry, for example, there are big differences in the degree of

concentration on specific journal titles. The total number of titles viewed was

broadly similar in the two disciplines; but the most popular 5% of titles

accounted for 39.5% of use in chemistry, as compared with 26.6% in physics.

Figure

4

UK higher education libraries expenditure and usage

of e-journals

Table

3

Information-Seeking

Behaviour - Readers in Different Subjects Behave Differently

|

|

Journal titles viewed |

Most popular 5% of

journals accounted for % use |

Page views (average

per session) |

Abstract views (%

sessions) |

Gateways (% page

views arriving via gateways) |

|

Chemistry |

196 |

39.5 |

3.2 |

23.3 |

49.2 |

|

Environmental

Sciences |

248 |

29.6 |

3.6 |

22.7 |

41.4 |

|

Economics |

132 |

46.9 |

3.8 |

30.4 |

19 |

|

Life sciences |

531 |

38.1 |

2.0 |

19.5 |

65.9 |

|

Physics |

204 |

26.6 |

2.5 |

20.1 |

57.8 |

There

are similar variations as to the average number of page views per session. It is

not obvious, for example, why environmental scientists should view nearly twice

as many pages during a session as life scientists do, though it may be related

to the latter’s much higher usage of external gateways, including services such

as PubMed. There is more consistency with regard to the use of abstracts: only

economists stand out as using them much more than scientists do.

Perhaps

more intriguing are the variations between users in the same discipline at different

institutions. Our analysis shows, for example, significant variations in

intensity of usage at our case study institutions. The following two charts

compare usage (in this case numbers of page views in the subject area concerned

as shown in the Science Direct logs) with the size of the institution in two

subject areas. The measure of size is the number of staff submitted to the 2008

Research Assessment Exercise (RAE), the exercise that has been undertaken

roughly every five years in the UK since 1986, to assess the quality of

research in each university in the UK. The number of staff submitted to the RAE

provides only a rough indication of size, since it does not take account of

numbers of research students or of staff (such as research assistants) who were

ineligible or who were not chosen for submission by their institution.

Nevertheless, it provides a reasonable indication of the weight of research

effort in each institution. In each of the graphs, the data are indexed to the

institution with the largest number of research-active staff in the subject

area.

What

is intriguing here is that intensity of use does not appear to be closely

correlated with size or with the quality of the research that is undertaken at

the universities concerned. In physics, for example, the quality ratings

achieved in the 2008 RAE by Cambridge, Edinburgh, Manchester, and University

College London were fairly similar. The striking variation – by a factor of four – in the ratios between levels of use

and of size at Edinburgh and UCL on the one hand, and Manchester on the other,

is not explained simply by either the volume or the quality of the research

being produced at those institutions. There are similar variations, by as much

as a factor of six, in the age of the articles that are viewed in different

subjects and institutions; and again these do not seem to be related to levels

or quality of research performance at individual institutions.

Variations

in the titles viewed at different institutions seem to show, however, a more

understandable pattern. Table 4 shows the average impact factor of the journals

viewed at the case study institutions. Since impact factors vary considerably

between disciplines, we have sought to normalise for the range of disciplines

at each institution, by calculating a “relative impact” factor, which matches

each journal viewed against the average for that discipline. Thus a value of 1

means that the journals viewed at that institution are typical—in terms of

their citation impact—of the journals for that range of disciplines as a whole,

worldwide. A value greater than 1 means that users at that institution are

viewing articles in journals with an impact factor higher than the average in

that range of disciplines. What is notable here is that users

at the most research-intensive universities (Cambridge, Edinburgh, Manchester

and UCL) are using journals that are more heavily cited than the global average

in their disciplines. Users at other institutions, including the two

Government-funded research institutes (the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and

the Rothamsted agricultural research institute) tend

to use journals where the impact factor clusters around the average.

Figure

5

Usage

comparison – size of institution in two subject areas

Such

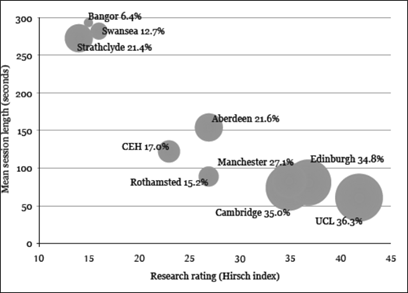

variations may well be related to differences in how users in different

institutions get to content. Users at the more research-intensive universities

tend to make more use of gateways such as Google Scholar and PubMed, and then

to spend less time on a journal site than their colleagues in other

institutions. Figure 6 shows the average session length in Science Direct for

users at each of our case study institutions in the life sciences, mapped

against the research rating of the authors at each institution as measured by

the Hirsch index. The percentages indicate how many Science Direct sessions

originated from an external gateway service, and the diameter of the circles is

scaled to that value.

We

can also derive similar patterns when we look at usage of navigation facilities

within the Science Direct platform, with users at the less-research-intensive

institutions making much more use of menus and search facilities, especially

citation search. They also make more use of value-added services such as

alerts, and articles in press.

The

conclusions from this part of our work are that there are strong variations

between users not only in different disciplines but also in different institutions, and that some – but

not all – of the variations seem to be related

to the size and research-intensity of the institution. Such variations also

raise questions, of course, about the utility and value of some of the services

provided by libraries and publishers, particularly when services such as

advanced search are used only infrequently. One conclusion from our findings is

thus the familiar one that one size does not fit all. It is already well

understood that researchers in different disciplines behave differently and

have different needs. What has perhaps been less well covered in the literature

has been the differences in behaviours, and presumably needs, between users in

different institutions.

Relationships

between usage and value

We

have already noted that there are close relationships between expenditure on

and usage of e-journals; and those relationships remain strong even when we control

statistically for institutional size. Trying to assess the impact or value of

usage is more difficult. For the linkages between use of information resources

provided by libraries on the one hand, and research or learning outcomes on the

other are difficult to pin down, and chains of reasoning may raise as many

questions as they seek to answer. One approach is to try to calculate the

return on investment (ROI) for individual libraries. Recent studies (Tenopir, King, Mays, Wu, and Baer, 2010) suggest that the

ROI varies from between 15.5: 1 to under 0.64:1 (i.e., a negative return),

depending on such factors as the balance between teaching and research, and the

subject mix, at each university.

Table

4

Average

Impact Factor of the Journals Viewed at the Case Study Institutions

|

Case study |

Average impact factor of journals viewed |

Relative impact |

|

Aberdeen |

3.0 |

1.2 |

|

Bangor |

2.3 |

0.9 |

|

Cambridge |

5.0 |

2.0 |

|

Centre for Ecology and Hydrology |

2.6 |

1.0 |

|

Edinburgh |

3.7 |

1.5 |

|

Manchester |

3.9 |

1.6 |

|

Rothamsted |

2.6 |

1.0 |

|

Strathclyde |

2.7 |

1.1 |

|

Swansea |

2.5 |

1.0 |

|

UCL |

4.1 |

1.7 |

Figure

6

Session length and gateways

We

have taken a rather different approach, seeking to investigate the relationships

between levels of usage on the one hand, and a range of measures of research

activity on the other. We first of all identified from our analysis of the data

across the UK sector three groups of universities in terms of the volume of

downloads: moderate, high and super users. In Table 5, we match these groups

with various measures of research activity as well as a calculation of cost per

download.

These

figures suggest that there might be a relationship between e-journal usage and research

performance: the differences in performance between the groups are

statistically significant, although differences in cost per download are much

less so.

We

then moved to a more detailed mapping of article downloads in individual

universities plotted against similar measures of research performance, as

shown, for example, in Figure 7.

Table 5

Usage groups and research outcome measures

|

|

Moderate users (n=80) |

High users (n=25) |

Super users (n=10) |

|

Research papers per

academic |

0.4 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

|

Research grants and

contracts per academic (£000’s) |

12.7 |

29.0 |

39.7 |

|

PhD awards per 100

academics |

9.1 |

17.5 |

17.4 |

|

Cost per download |

£0.89 |

£0.74 |

£0.60 |