Introduction

This paper evaluates student references included in assignments

when a single presentation (“one-shot”) and embedded instruction techniques are

used, and contributes to the ongoing conversation among instruction librarians

regarding which method is most effective. As awareness of the skills needed by

students that are encompassed in information literacy grows, requests for

librarians to participate in classes also grows, and finding ways to most

effectively teach the content so it does not need to be repeated in later years

is critical. Purdue University is working toward a more embedded approach for

information literacy whenever possible. Nearly all incoming freshmen at Purdue

are required to take the Fundamentals of Speech Communication course. Demonstrating and implementing more effective teaching techniques

for this course will impact a large majority of freshmen students across

disciplines. Having some empirical evidence to support the benefits of

this model facilitates the conversation with faculty, (particularly engineering

faculty) who appreciate data-driven decision making.

Literature Review

One-shot library sessions are generally considered to

be less impactful than other instruction presentation styles (Badke, 2009; Hollister & Coe, 2003). Orr, Appleton, and

Wallin (2001) make a clear argument for moving away

from the “one-shot” instruction model:

It has became [sic] clear that the “one-off,” demonstration-style

information skills classes delivered out of curriculum context do not

necessarily coincide with the students’ need for information, are sometimes not

valued by the students, and do not necessarily prepare them for the challenges

of research, problem solving and continuous learning. Where possible,

librarians prefer to use an across-the-curriculum model that incorporates the

process of seeking, evaluating, and using information into the curriculum and

consequently, into all students’ experiences. (p. 457)

One-shot instruction sessions have been tested for

impact upon student work with varying outcomes (Byerly,

Downey, & Ramin, 2006; Fain, 2011; Martin, 2008).

Generally, the increased integration of content into the curriculum leads to

more positive student outcomes (Jacobs & Jacobs, 2009; Stec,

2006).

The integration of information literacy into the

curriculum presents the most opportunity for successful knowledge transfer of

information literacy, as well as the highest barrier to entry for librarians

(Bean & Thomas, 2010; Brendle-Moczuk, 2006; Hall,

2008; Hollister & Coe, 2003; Jacobs & Jacobs, 2009; Weaver & Pier,

2010). Integration into the curriculum

has benefits both for acquired skills for the students as well as for exposure

and comfort with the librarian/instructor (Bean & Thomas, 2010; Gandhi,

2005; Weaver & Pier, 2010). Project Information Literacy research has determined

that a major need for undergraduate researchers is to have context for the

learning objectives. Providing instruction in the context of an assignment

fills a crucial need for undergraduates (Head & Eisenberg, 2009a).

Communication courses, by virtue of the secondary research required to prepare

basic speeches, are particularly good venues for curriculum-embedded information

literacy (Hall, 2008; Weaver & Pier, 2010). Creating speeches on a variety

of topics should allow students to explore a variety of resources. However, as

Head and Eisenberg have found, “Most respondents, whether enrolled in a two- or

four-year institution, almost always turned to a small set of information

resources, no matter which research context they were trying to satisfy” (2009b, p. 32).

The variety of assignments encourages expanding the

freshman students’ information toolkit, thereby increasing available tools for

future assignments. Freshman engineers generally are unskilled in the practice

of information literacy skills, as shown by the predominance of websites in

freshman bibliographies (Yu, Sullivan, & Woodall, 2006). Yu

et al. (2006) emphasized “finding, interpreting, and citing books, journal

articles, and Web sites” (p. 21) as the primary skills that are necessary for

freshman engineers. Hsieh & Knight (2008) concluded that the

traditional lecture is ineffective for teaching freshman and sophomore

engineers. The information literacy skills needed by first-year engineering

students are generally part of an introduction to design. Bursic

and Atman (1997) investigated the differences in information-gathering skills

between seniors working on a design project and those just beginning to learn

design. The designs from the first-year students are less complete and lack the

contextual awareness and understanding of usefulness and applicability of

designs that develop as a result of information gathering.

This study investigates the performance of first-year

engineering students during an introduction to a communications course when

exposed to two different modes of presentation, a just-in-time model and a

one-shot model. The literature indicates

that the just-in-time model of instruction is likely to be more effective at

building information literacy skills among the students (Hall, 2008; Martin,

2008; Weaver & Pier, 2010). Using a citation analysis model developed

specifically to examine bibliographies and outline deliverables of engineering

undergraduate students (Wertz, Ross, Fosmire, Cardella, & Purzer, 2011),

this article seeks to demonstrate that the mode of instruction results in an

increased information literacy of a students in a class and expands on a

work-in-progress conference paper (Van Epps & Sapp Nelson, 2012).

Aims

Research Question

Is there a noticeable difference in the quality, type

of resource, and completeness of the references in student assignments when

“just-in-time” instruction is used as opposed to a “one-shot” session?

The researchers’ hypotheses are that the sections

which received the just-in-time instruction will have more references and

better citations, in quality, type of resource, and completeness, than the

section which received the one-shot session at the start of the semester. All

three of the unique questions embedded in the research question as stated will

be tested and reported.

Methods

Setting/Courses

Researchers studied a group of first-year engineering

students enrolled in three sections of COM 114, Fundamentals of Speech

Communication, a course that focuses on oral

communication skills for students in all disciplines. Several sections of the

class are associated with learning communities

(Student Access Transition & Success, 2011a, 2011b), and as a result have

only engineering students enrolled. In preparation for assignments in COM 114,

two different course instructors contacted engineering librarians to have them

present library resources to assist students with the information gathering

portion of the four speech assignments to be completed during the semester. Two

sections received information in four 12-minute, integrated information

literacy instruction sessions (otherwise known as “just-in-time”), prior to the

assignment that the instruction was intended to support. One section was given

a traditional “one-shot” instruction session of 50 minutes during the second

week of the semester, before any of the assignments had been given. All of the

students received an equivalent duration of library instruction, just divided

differently. Instruction librarians used the same materials and supporting LibGuide for all sessions offered. The LibGuide

(http://guides.lib.purdue.edu/com114engr) uses four tabs, one for each

assignment. During the one-shot session, all four tabs were addressed during

the 50 minutes, while during the mini-lectures, the

librarian presented a single tab in each session. The LibGuide

and accompanying instruction provides guidance for the students in selecting

from a variety of sources appropriate within the context of the assignment. The

library instruction focused on the best resources for the types of speeches the

students would be giving, in support of the course objective of being able to

“use supporting material properly and effectively” when making a presentation

(http://www.cla.purdue.edu/communication/documents/COM114_Syllabus2011.pdf).

All COM 114 classes are taught in traditional lecture-style classrooms with a

computer and projector available in the front of the room. In all cases,

librarians used a demonstration/lecture-style of material presentation.

Description of Assignments

Table 1 presents an overview of each of the four

assignments, including the focus of the speech, expected deliverables, and an

indication of whether the assignment is for individual or group submission.

Table 1

Expected Deliverables for COM 114 Engineering Living

Learning Community Students

|

Assignment 1

|

Informative Speech – Engineering Innovation

|

Outline & Bibliography

|

Individual Submission

|

|

Assignment 2

|

Informative Speech – Process speech

|

Outline & Bibliography

|

Individual Submission

|

|

Assignment 3

|

Persuasive Speech – Charitable Donation

|

Outline & Bibliography

|

Individual

Submission

|

|

Assignment 4

|

Group Presentation – Description of an Engineering

Innovation

|

Outline & Bibliography

|

Group Submission (3-4 individuals)

|

See Appendix A for the complete assignment

descriptions.

Sample

The population consists of all students enrolled in three

engineering learning community sections of COM 114 included in this study

(n=75). The data consists of the student deliverables (outlines and

bibliographies) for all individual and group assignments in these sections. The

full data set for four assignments in the three sections provided a total of

234 outlines and bibliographies. Equal sample sizes were used to represent the

just-in-time and one-shot sections. This was done to avoid skewed data which

may have resulted from having two sections of the class receiving just-in-time

(JIT)/embedded teaching (n=51) and only one receiving one-shot instruction

(n=24). The sample analyzed consisted of five papers for each individual

assignment per teaching team and three of the group papers from each team. Researchers

randomly selected papers from the set of possible papers for each teaching

team, and used two methods to randomly select assignments to review, based on

how the data was delivered to the librarians. The assignments from the

mini-lectures classes were numbered sequentially and a random number generation

website was used to identify which assignments would be analyzed. For the

one-shot section assignments, copies were printed and researchers randomly

selected the correct number of assignments from the pile.

Data Analysis Procedure

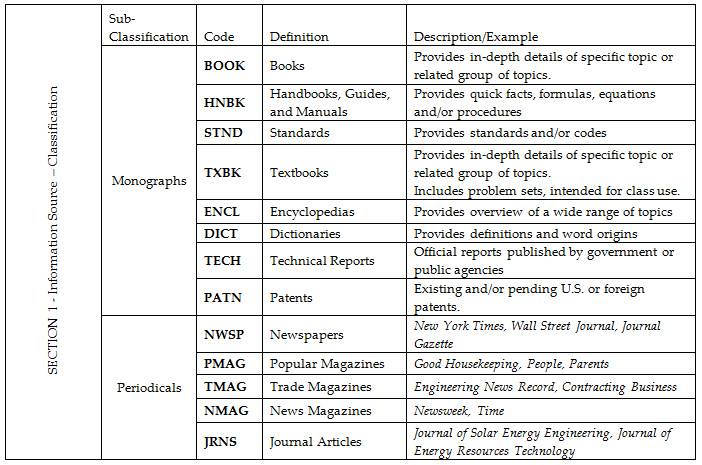

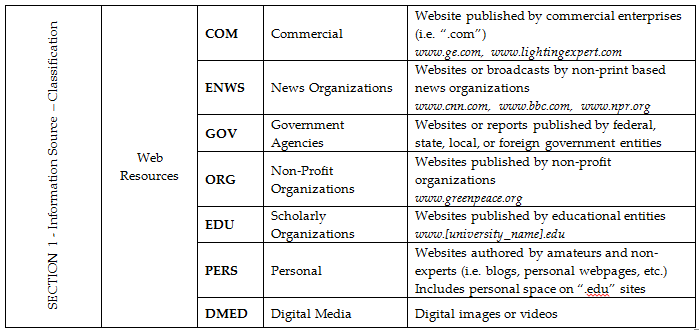

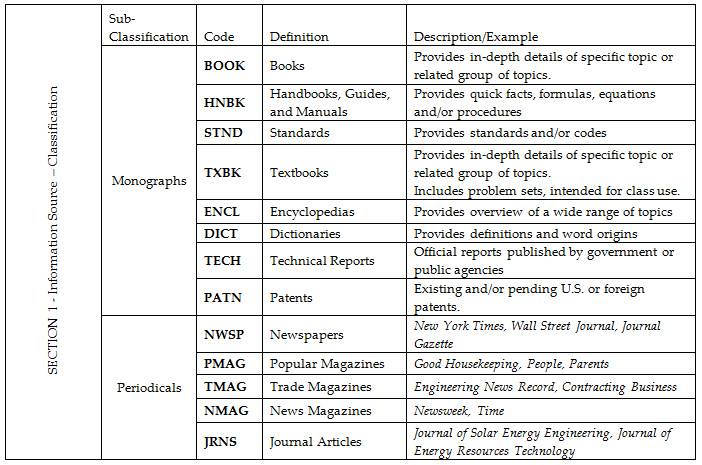

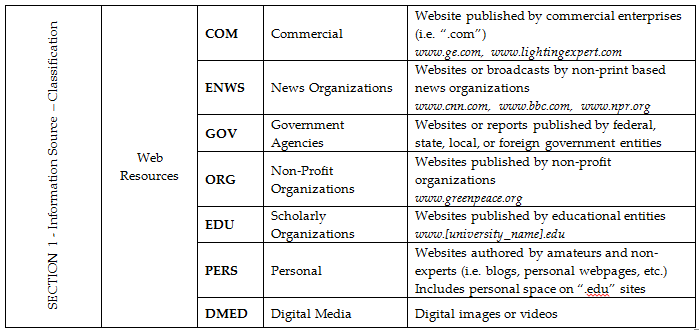

After removing any identifying information,

instructors sent the student assignments to the librarians. The librarians then

coded the references in each bibliography for type of information resource

used, quality of the resource based on its scholarly content and lack of bias,

and the completeness of the reference included. The coding framework is a

modification of that used by Wertz et al. (2011) and can be found in Appendix

B. Librarians then compared the quality of resources used, the completeness of

citations, and the types of resources used for the particular assignment across

the sections for each instructional team. A simple Z-test for comparison of

difference between proportions was then used for each rating given to the

references.

While it was impossible to control for the

instructor/librarian teaching style variations and differences inherent from

having different students in each class, librarians coordinated the content

presented and used the same LibGuide to ensure all

students shared a common resource to return to for guidance as the semester

progressed. In this way researchers controlled as many variables as possible to

control easily. Though they did not use a set script for delivery of their

respective presentations, the two librarians involved have similar teaching

styles.

One difference between the sections is due to multiple

librarian visits that provide an opportunity for a quick follow-up conducted as

a guided conversation of not more than three minutes. This provided the

students a chance to reflect upon which tools they used in the previous

assignment, how successful they felt they were with the tools, and why those

tools were appropriate for the previous assignment. However, this discussion

did not impact upon the upcoming assignment, as each assignment required the

use of different resources. The discussion did establish that some features of

databases (i.e., Boolean logic and operators, limiters, and faceted searching)

reappear across tools.

Inter-rater Reliability

Researchers used a simple percent-agreement figure to

calculate the consensus estimate of inter-rater reliability (IRR). This

calculation involved taking the number of items coded identically by different

raters and dividing by the total number of items rated (Stemler,

2004). Both raters analyzed an initial sample of 8 items from the original 234

items, representing one of each assignment for each instructional method, using

the framework developed by Wertz et al. (2011). Each citation is rated for type

of material, quality of resource based on both audience and treatment (bias),

and completeness of the citation, creating four ratings for each citation.

After rating the initial eight items, the two librarians met, checked how their

use of the framework aligned, and discussed differences to develop a common

understanding of the coding framework. The consensus estimate of inter-rater

reliability was calculated as 85.1%; a value above 70% for IRR indicates strong

agreement between raters in application of the framework (Stemler,

2004). The largest source of variation between raters came in determining

complete, incomplete, and improper citations, which accounts for 44% of the

differences in codes applied. These differences were discussed so that raters

could reach consensus prior to coding the full data. Finding a sufficiently

high agreement rate between raters meant the authors could trust that the

individual analysis of the citations would be sufficiently similar and that

each could rate half of the references lists to distribute the load. Raters

then divided the student outlines based on which presentation method was used,

such that each rater had half of the students they taught and half from the

other class. More clarity on improper and incomplete reference and what

constitutes “easily traceable” could bring the IRR up to 91.6%. Defining a

reference as findable meant that basic users could locate the item, rather than

requiring the skills of a librarian, who would use the other bits of information

present and require more time to track it down.

Coding Framework Modifications

During discussion between the two raters to verify

agreement on use of codes, several modifications were proposed to the coding

framework. Some required modifications resulted from applying the framework to

non-engineering-specific assignments and clarifying the application for the

current research. A full description of the modifications made from the

original used in Wertz et al. (2011) can be found in the work-in-progress

conference paper (Van Epps & Sapp Nelson, 2012).

Results

References Analysis

The sample of 36 bibliographies included 233

references for analysis to determine student use of resources and the ability

to document those sources. The bibliographies included an average of 6.5

references per outline (233/36=6.5), which may seem high for first-year

students in a speech class. The high average can partially be explained by the

team assignment that contained an average of 16.8 references per outline

(101/6=16.8) for all teams, thus skewing the average. Without the team

assignment, the average number of references per outline is 4.4 (132/30=4.4).

While this is still slightly higher than expected, based on an average of 3.57

references in first-year student papers found by Knight-Davis and Sung (2008),

it is a reasonable number given the first assignment required two sources and

the remaining three assignments all asked for a minimum of three citations.

When analyzing the number of references, the teaching

team discovered that the one-shot session students averaged 3.87 (58/15=3.8667)

references per individual assignment, and that the mini-lectures session

students averaged 4.93 (74/15=4.9333) references per outline.

Resource Quality

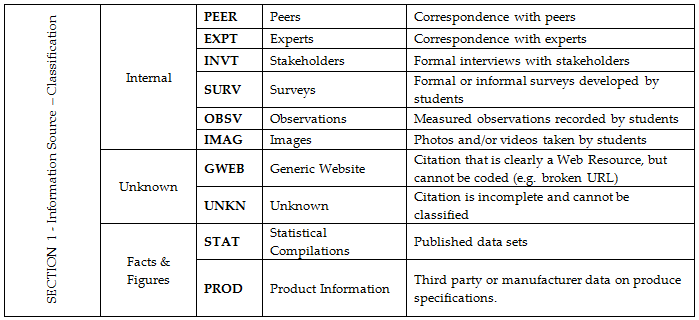

Using the quadrants presented by Wertz et al. (2011),

as illustrated in Figure 1, the 233 references were rated for quality. Of the

full set of 233, 6 were removed from the quality assessment because they were

coded as general web (GWEB) resources or unknown (UNKN), and with a broken link

it was impossible to determine audience or intent of the resource.

Figure

1

Quality

of resources

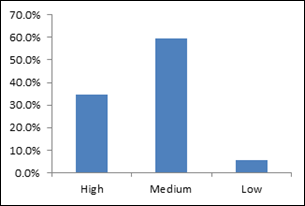

As shown in Figure 2, the remaining 227 references

were analyzed: 34.8% were high quality (scholarly and informative), 59.5% were

medium quality (popular and informative, or scholarly and biased), and only

5.7% were low quality (popular and biased or entertainment).

Figure

2

Percent

for each quality

Cross-section Analysis

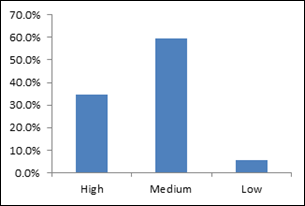

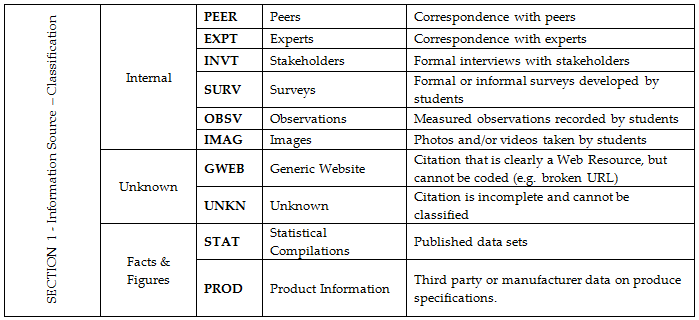

For the cross-section analysis, researchers divided

the assignments into two sets by type of library instruction the students received,

one-shot or four mini-lectures. The one-shot session included 109 references

and the mini-lectures session included 124 references. Both groups had three

citations that were removed due to broken links or unknown materials type.

The one-shot section presented the following

break-down of references by quality: 2.7% unable to be classified due to broken

links, 22.9% high quality, 65.2% medium quality, and 9.2% low quality. The

mini-lectures section presented a different pattern, with 43.6% high quality,

51.6% medium quality, and 2.4% low quality. Figure 3 shows the differences

between sections based on the quality of resources used. High (Z=3.31,

p<.001), medium (Z=-2.06, p<.05), and low (Z=2.24, p<.05) quality

ratings all show statistically significant differences between the sections.

Figure

3

Quality

of resources cited

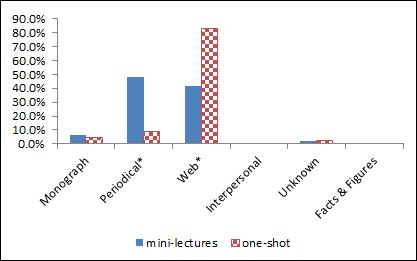

Analysis of the references based on the type of

resources used (Figure 4) shows a statistically significant difference between

sections for use of periodicals (Z=6.52, p<.001) and Web resources (Z=-6.50,

p<.001). The mini-lectures section exhibits more use of periodical sources,

while the one-shot section used more Web resources.

Figure

4

Type

of resources

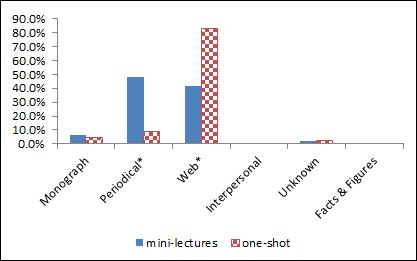

Figure 5 shows the variation of types of resources

used for each assignment in both groups. Each assignment shows a pattern very

similar to the overall type of resources analysis. The students who received

the mini-lectures show more variation in the types of resources used, while the

students who received the one-shot lecture do not appear to have changed their

information use patterns, consistently using mostly Web resources.

Figure

5

Types

of resources used by assignment

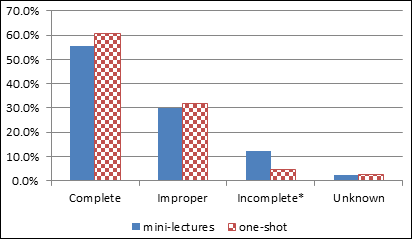

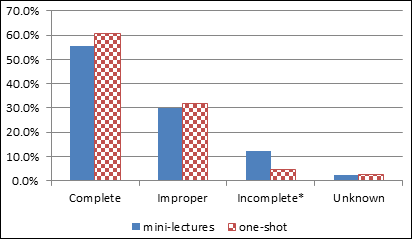

Figure 6 shows the differences between sections for

the completeness of the references. The only statistically significant

difference can be seen in the incomplete category (Z=2.03, p<.05) and may

reflect differences between raters more than differences in student abilities.

Librarians did not teach proper APA format, and identification of a reference

as complete required only the presence of all elements of the reference, not full

punctuation and formatting. For the majority of the assignments in both teams

(55.7% JIT; 60.6% one-shot), the students included all necessary elements for a

complete citation.

Figure

6

Completeness

of references analysis

Discussion

Results indicate that the presentation of information

just prior to the completion of an assignment led to an increased number of high-quality

resources being cited in student bibliographies. This supports the researchers’

hypothesis. Those students who were exposed to the just-in-time sessions

performed in a way that indicates that four 12-minute sessions throughout the

term improves knowledge transfer of information literacy skills. While the same

content was presented, the librarian offering the mini-lectures noted the

ability for quick follow-up from the preceding assignment and a progression in

the learning about library resources. While this practice generated a small

difference in delivery, it was a natural outgrowth of repeated visits to the

class and a desire from the students to understand why the sources for the

preceding assignment were not adequate for the current assignment.

The fact that the primary learning goals of the course

were not technical (i.e., a speech communications course) influenced the use of

popular and informative resources (medium quality at 59.9%). The researchers

were unsurprised by this result, particularly given the topic of assignment 3,

the persuasive speech about a charitable organization. Researchers coded 93.4%

of the resources as informative, while only a small percentage of the resources

were coded as biased, even for the charity assignment, a likely situation for

integrating biased information. Course instructors provided

the grading and feedback returned to the students. Therefore, the

authors have no indication of the content, quality, or consistency of feedback

that students were given on practice of information literacy skills as

evidenced in the outlines and bibliographies.

The analysis of the number of complete references per

assignment revealed consistent patterns across sections of 50%-65% complete on

all four assignments. Again, librarians did not teach reference formatting, and

completeness simply signals that all the necessary components were present. The

majority of complete references pattern holds even for the third assignment,

where the necessary resources were mostly websites. The authors see this as an

encouraging sign that students understand that more than just a URL is required

to identify websites in citations.

Conclusions

The statistical analysis of student bibliographies

indicates that the introduction of information literacy instruction for several

brief lectures in conjunction with gateways or assignments in the curriculum

improves outcomes. It cannot be determined if the changes in instruction model

are the sole reason for observed variations, or if the section instructors

impacted the outcomes through differences in teaching or grading.

This project presents intriguing possibilities for

future research. A continuation of the study reported here within a different

course, focusing on technical information, could explore if information

literacy skills practiced in speech class are transferred into technical

courses. Repeating a similar experiment, but using two or more sections of the

speech class taught by the same instructor, could indicate the extent that

instructor input impacts the outcomes of this experiment. Building upon the observation that the group

speech had much higher-quality resources and more complete citations, a study

may also investigate if the use of group work helps to improve the information

literacy skills of the group as a whole.

Acknowledgements

This paper is an extension of a conference paper that

presented preliminary findings and was published in the Proceedings of the 2012

ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition by the same authors. The authors want to

thank Jennifer Hall and Elizabeth Wilhoit for

requesting the library instruction sessions and assisting the research by

providing anonymized copies of student work. The

research was approved by the Purdue University Institutional Review Board (IRB),

protocol number 1109011287.

References

Badke, W. (2009). Ramping

up the one-shot. Online, 33(2), 47-49.

Bean, T. M., & Thomas, S. N. (2010). Being like both: Library instruction methods that outshine the

one-shot. Public Services Quarterly, 6(2-3), 237-249.

doi:10.1080/15228959.2010.497746

Brendle-Moczuk, D.

(2006). Encouraging students’ lifelong learning through graded information

literacy assignments. Reference Services Review, 34(4), 498-508. doi:10.1108/00907320610716404

Bursic, K. M., & Atman, C. J. (1997).

Information gathering: A critical step for quality in the design process. Quality Management Journal, 4(4), 60-75.

Byerly, G., Downey, A., & Ramin, L. (2006). Footholds and foundations: Setting freshmen on the path to lifelong learning.

Reference Services Review, 34(4), 589-598. doi:10.1108/00907320610716477

Fain, M. (2011). Assessing information literacy skills development in first year

students: A multi-year study. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 37(2), 109-19.

doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2011.02.002

Gandhi, S. (2005). Faculty-librarian collaboration to

assess the effectiveness of a five-session library instruction model. Community

& Junior College Libraries, 12(4), 15-48. Retrieved 3 Mar. 2013

from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J107v12n04_05

Hall, R. A. (2008). The “embedded” librarian in a freshman speech class:

Information literacy instruction in action. College & Research Libraries

News, 69(1), 28-30. Retrieved 3 Mar. 2013 from http://crln.acrl.org/content/69/1/28.full.pdf+html

Head, A., & Eisenberg, M. (2009a). Finding context: What today’s college students say about conducting research in

the digital age. Seattle, WA. Retrieved 3 Mar. 2013 from http://projectinfolit.org/pdfs/PIL_ProgressReport_2_2009.pdf

Head, A., & Eisenberg, M. (2009b). Lessons learned: How college

students seek information in the digital age. Seattle, WA. Retrieved 3 Mar.

2013 from http://projectinfolit.org/pdfs/PIL_Fall2009_finalv_YR1_12_2009v2.pdf

Hollister, C. V., & Coe, J. (2003). Current trends vs. traditional models: Librarians’ views on the methods

of library instruction. College and Undergraduate Libraries, 10(2),

49-63. doi:10.1300/J106v10n02_05#

Hsieh, C., & Knight, L. (2008). Problem-based learning for engineering students: An evidence-based

comparative study. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34(1),

25-30. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2007.11.007

Jacobs, H. L. M., & Jacobs, D. (2009). Transforming the one-shot library session into

pedagogical collaboration: Information literacy and the English composition

class. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 49(1),

72-82. Retrieved 3 Mar. 2013

from http://rusa.metapress.com/content/q7508652x22vl4t1/fulltext.pdf

Knight-Davis, S., & Sung, J. S. (2008). Analysis of citations in undergraduate papers 1.

College & Research Libraries, 69(5), 447-458. Retrieved 3

Mar. 2013 from http://crl.acrl.org/content/69/5/447.full.pdf+html

Martin, J. (2008). The information seeking behavior of undergraduate

education majors: Does library instruction play a role? Evidence Based

Library and Information Practice, 3(4), 4-17. Retrieved 3 Mar. 2013

from http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP/article/view/1838/3696

Orr, D., Appleton, M., & Wallin,

M. (2001). Information literacy and flexible delivery: Creating

a conceptual framework and model. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 27(6), 457-463. doi: 10.1016/S0099-1333(01)00263-4

Stec, E. (2006). Using best practices: librarians, graduate students and

instruction. Reference Services Review, 34(1), 97-116. doi:10.1108/00907320610648798

Stemler, S. E.

(2004). A comparison of consensus, consistency, and measurement approaches to

estimating interrater reliability. Practical

Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 9(4). Retrieved 7 Jan.

2013 from http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=9&n=4

Student Access Transition & Success. (2011a). College of engineering learning communities.

Retrieved 5 Mar.

2012, from http://www.purdue.edu/sats/learning_communities/profiles/engineering/index.html

Student Access Transition & Success. (2011b). Learning communities. Retrieved 5 Mar. 2012, from http://www.purdue.edu/sats/learning_communities/index.html

Van Epps, A. S., & Sapp Nelson, M. (2012). One or Many? Assessing

different delivery timing for information resources relevant to assignments

during the semester: A work-in-progress. Proceedings

of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition. San Antonio, TX:

American Society for Engineering Education.

Weaver, K. D., & Pier, P. M. (2010). Embedded information literacy in the basic oral communication course:

From conception through assessment. Public Services Quarterly, 6(2-3),

259-270. doi:10.1080/15228959.2010.497455

Wertz, R. E. H., Ross, M. C., Fosmire, M., Cardella, M. E., & Purzer, S.

(2011). Do students gather information to inform design decisions? Assessment with an authentic design task in first-year engineering.

Annual Conference and Exposition of the American Society

for Engineering Education (pp. AC 2011-2776). ASEE.

Yu, F., Sullivan, J., & Woodall, L. (2006). What can students’ bibliographies tell us? Evidence based information

skills teaching for engineering students. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 1(2), 12-22. Retrieved 3 Mar. 2013 from http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP/article/view/8/123

Appendix A

Description of Speech Assignments

Network Learning Community

COM 114 Speech Assignments

Speech #1: Informative

Length: 3-4 Minutes

Description: In this speech, you will present to the class about

one of the top Engineering innovations of the 20th century. You will

be given a list of topics from your instructor. You will explain to the class

what the innovation was and what impact this innovation has had on the way that

people live, work, or how we understand the world. This assignment will require

a small amount of research, and each presentation must include two sources.

This assignment emphasizes organization and delivery. It is important that you

present the material in an appropriate organizational pattern for an oral

presentation. You must have an introduction, body, and conclusion. This will

help your audience understand and retain the information you provide. You also

will be asked to pay specific attention to your delivery.

Speech #2: Informative

Length: 4-5 Minutes

Description: In this speech we will be focusing on how to report

information to different audiences with differing levels of knowledge. For this

assignment the class will be divided into groups of three. Each small group

will be assigned a machine, process, or technological innovation works. Each

individual in the group will also be assigned a target audience; fellow

engineers, potential consumers, or high school juniors. Although the groups of

three will have the same topic and will present on the same day, you do not

need to collaborate on your presentations. Your task will be to explain how

this machine, process, or technology works in a way that is appropriate for

your target audience. This presentation must be based on at least 3 sources and

use an appropriate organizational pattern and include a clear intro, body, and

conclusion.

Speech #3: Persuasive

Length: 5-6 Minutes

Description: For this presentation you are going to persuade your

classmates to support a charity or nonprofit organization by donation their time,

money, or tangible goods. You are going to persuade your audience to volunteer

or to donate money or other tangible goods. You will use a problem-solution

format. First explain what the problem is and then explain why your audience

should support the organization you chose to help that problem. For example,

you might want to persuade your audience to donate blood. You would first talk

about the problem which is the need for blood and possible blood shortages and

then explain how being a blood donor can help solve that problem. You can also

talk about the personal benefits one might get from supporting the cause you

chose. These can be national or local organizations.

Speech #4: Group Presentation

Length: 30-35 Minutes

Notes: 1 typed sheet OR 1 4x6 notecard per person

Description: In this speech, you must take various

concepts/products (a car, a computer, a home, a classroom, a restaurant, etc.)

and completely RETHINK the object or space to make it more user-friendly and/or

efficient. You must develop visuals of your new product so the audience can

visualize it. Your audience for this speech is a venture capital firm, so be

sure to “pitch” your product as well as you can.

Appendix B

Coding Framework for Speech Outlines

![]() 2013 Van Epps and Nelson.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2013 Van Epps and Nelson.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.