During a virtual briefing held by the Women in STEM Caucus and The Science Coalition, Patricia Clark, the Rev. John Cardinal O’Hara, C.S.C., Professor of Biochemistry at the University of Notre Dame, said that women in science are being pushed past the point of no return due to the ongoing strain of the COVID-19 pandemic combined with longstanding structural barriers — threatening permanent damage to their careers.

“Under the best of times, there are still deep structural issues that present barriers to women’s participation in science,” Clark said in her remarks. “And this includes the fundamental incompatibility between the expectations of the tenure clock and society’s expectations of women as caregivers, especially as mothers.”

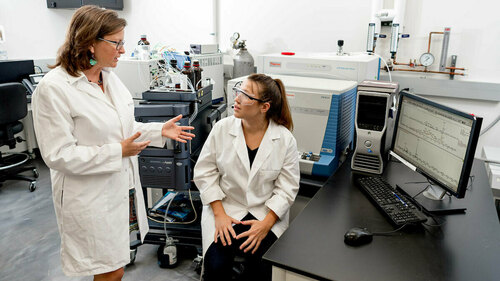

Clark is a concurrent professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering and leads a W. M. Keck Foundation-funded research project to investigate the effects of protein synthesis rates on the success or failure of protein folding. She also directs the Biophysics Graduate Program and the Biophysics Instrumentation Core Facility at Notre Dame.

A bipartisan group, the Women in STEM Caucus is dedicated to advancing the role of women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) and works to promote partnerships between universities, federal research agencies and the private sector to support scientific breakthroughs led by women researchers. The March 24 briefing was aimed at addressing the unique challenges posed by the pandemic to women in STEM.

The co-chairs of the Women in STEM Caucus, Rep. Chrissy Houlahan and Rep. Jackie Walorski, along with Rep. Debbie Lesko and Rep. Haley Stevens said the pandemic has “laid bare the many inequities that we already knew faced women in the workforce, particularly mothers and those who serve as primary caregivers for their families.”

An estimated 3 million women have left or have been forced out of the workforce since the pandemic began. Houlahan added that while women account for 52 percent of the college-educated workforce in the U.S., they account for only 29 percent of the science and engineering workforce. Lack of diversity also remains an issue, Houlahan said, with underrepresented groups accounting for only 13 percent of the workforce in science and engineering.

Despite the barriers often faced, Clark said women in STEM fields have been able to carve out successful, productive careers for themselves — thanks in part to luck and a willingness to work harder than anyone else.

“At various times during my career I’ve needed to work much harder than my male colleagues in order to be successful,” she said. She credited the good fortune of a supportive spouse, a healthy child, parents who are aging but independent and in reasonably good health, and financial means — which is not always the case for everyone.

“All around me I see younger women every day — graduate students and postdocs and assistant professors — all of whom are still more likely than men to get tripped up due to the structural barriers I mentioned,” said Clark. For women of color and women who are caregivers or dealing with health concerns, those odds are even greater.

“Now, on top of those longer odds for women we have a pandemic,” she said. “Everyone now has a greater chance of failure because there are new, pandemic-related ways to fail.”

Clark added she’s seen firsthand how those who are more vulnerable have been affected by the additional strain of a global pandemic.

A female postdoctoral fellow navigating the transition to assistant professor “delayed the start of her faculty appointment for a year because she simply couldn’t cope with the idea of trying to move across the country with a toddler, finding a new daycare that she could trust, starting her research laboratory and teaching remotely all at the same time,” she said.

For women in academics, pre-tenure years are the most demanding, and those trying to balance the needs of their careers with young children at home face the likelihood of feeling pushed into a corner and having to choose one over the other.

A report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine on the impact of the pandemic on women in academia found 90 percent of women faculty were managing the majority of child care demands.

“The homeschooling aspect, the all-of-a-sudden all of us are homeschoolers aspect, in my own anecdotal experience … definitely had a larger impact on women versus men.”

To help level the playing field, said Clark, “money helps, and time helps and flexibility helps.” She also said a strong public school system and caregiving structures help with the fundamental and societal expectations so often placed on women.

“Everyone’s issues are different,” she added. “It’s not a one-size-fits-all solution, but there are definitely broad categories — things like schooling, things like child care, things like elder care — that definitely are large concerns for many women.”

Contact: Jessica Sieff, assistant director of media relations, 574-631-3933, jsieff@nd.edu