It is extremely rare to find evidence from the colonial period that contains the words of enslaved people — because they were usually denied access to literacy and because slavery attempts to strip the enslaved of their identity and individuality.

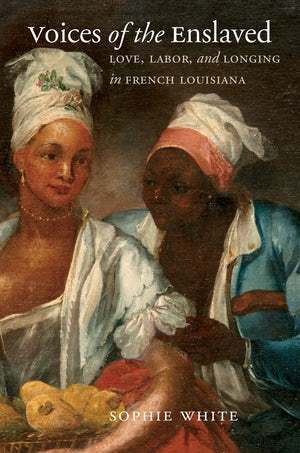

Sophie White, a professor in the Department of American Studies at the University of Notre Dame, offered an exceptional glimpse into the lives of the enslaved — through their own words — in her latest book, "Voices of the Enslaved: Love, Labor, and Longing in French Louisiana."

She recently won two awards for the work — the Kemper and Leila Williams Book Prize from the Historic New Orleans Collection and the Louisiana Historical Association and the 2020 Summerlee Book Prize from the Center for History and Culture of Southeast Texas and the Upper Gulf Coast at Lamar University. White also received an honorable mention for the Merle Curti Award for best book in American social history from the Organization of American Historians — which is only the third time in its 42-year history that an honorable mention has been awarded.

With support from a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities — her second such award — White uncovered and analyzed courtroom testimony from enslaved Africans in 18th-century Louisiana who testified as defendants, witnesses and victims.

Because of judicial procedure, she found, these individuals were given a rare public forum — providing testimony that was anchored in their own experiences and brimming with character, personality, wit and emotion.

“What ultimately shaped my vision for the book — my ‘aha moment’ — was the realization that in answering questions in an interrogation, they constantly redirected the court’s focus away from the crimes being investigated,” White said. “They veered off subject and offered details that seem extraneous at first glance but are, in fact, deeply revealing and often riveting.”

Many seized the opportunity to voice their experiences of slavery and removal from their homelands — turning forced testimony into an opportunity for autobiographical narrative.

“It is no longer about the court case,” she said. “It becomes about other things they want to share, which is what makes this archive so interesting — especially where the voices of enslaved women are concerned because this kind of evidence is so rare.”

"Voices of the Enslaved," the judges for the Summerlee Book Prize wrote in a news release, represents “a tour de force of interdisciplinary historical scholarship” and blends legal, cultural and material history to reveal deep connections between the enslaved world of New Orleans and the societies and cultures of the Caribbean and West Africa.

“I am thrilled and honored to be recognized for my contributions to my areas of specialization,” White said. “Because this source material is so important, I chose to write this scholarly book in a style that I hope is nonetheless approachable, in order to more widely disseminate this material and have these voices reach a wide readership.”

White, a concurrent associate professor in the Department of Africana Studies, the Department of History and the Program in Gender Studies, is also developing a digital humanities website related to the project, called Hearing Slaves Speak in Colonial America, which will provide, side-by-side, an image of the original court manuscript page, a transcription of the French and her translations and explanations of specialized terms.

“Because I could only write in depth in the book about eight individuals — though many, many others appear along the way — I wanted to develop a website that could showcase some of the other trials,” she said. “By including the entire trial transcript in this manner, I hope that it can become an effective teaching tool and that it will also be of interest to the lay reader.”

White also brings an emphasis on the lives of individuals to her courses on the history of slavery in colonial America and the Caribbean.

“Students write a research paper in which they research one individual, usually from a runaway-slave advertisement,” she said. “As I often remind them, they may be the only person who has spent so much time trying to learn about that individual, and they owe it to that person to help extricate them from the anonymity that slavery enforces on its subjects.”

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on April 30.