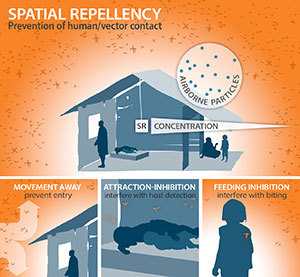

Spatial repellents can control

Spatial repellents can control

the transmission of diseases.

Image credit: Kristina Davis, University of Notre Dame

(click for larger view)

University of Notre Dame biologists Nicole Achee and Neil Lobo are leaders of an international $23 million research grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Their five-year project will generate the data required to show the effectiveness of a new paradigm in mosquito control — spatial repellency — for the prevention of two important mosquito-borne diseases: malaria and dengue fever.

The grant is the second largest award to a single grant proposal in Notre Dame’s history. A Microelectronics Advanced Research Corp. award to fund the Center for Low Energy Systems Technology totaled $29 million and is the largest award to a single grant proposal.

According to the World Health Organization’s latest global estimates, 207 million cases of malaria were reported in 2012, with 50 million to 100 million dengue infections occurring every year. Both the malaria parasite and dengue virus are transmitted through the bites of infected mosquitoes. Despite decades of organized mosquito control efforts, the diseases caused by these pathogens remain significant global health problems. Current global adult mosquito control strategies such as insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor residual spraying for malaria and space-spraying for dengue can be effective under certain circumstances, but are limited in combating the transmission of these pathogens in all areas where the diseases occur. This reality has left an urgent need to advance the development of novel products based on new paradigms, including spatial repellency, especially with the call to eradicate malaria and the increased burden of dengue.

Nicole Achee

Nicole Achee

Achee and Lobo, co-principal investigators and research associate professors in the Department of Biological Sciences, are members of the Eck Institute for Global Health. Their project, titled “Spatial Repellent Products for Control of Vector-borne Diseases,” will measure the benefit of using a spatial repellent product to prevent human infections with malaria parasites and dengue virus, transmitted to humans by multiple Anopheles species. The project will operate through two separate, but integrally related work streams: one focused on generating the scientific evidence required to demonstrate the effectiveness of the intervention and the other to inform global health policy.

Throughout the project, Achee and Lobo will present and discuss findings that can then be used by global, regional and local public health authorities for consideration in the development of a recommendation that spatial repellents be included in disease control programs, thereby improving the quality of life in at-risk human populations. Spatial repellents may be offered as stand-alone tools where no other interventions are implemented, or most likely, combined with existing interventions to enhance efficacy of other mosquito control strategies. When used with other interventions, repellents may manage the spread of insecticide resistance and intervene in areas of the mosquito’s life cycle where other products do not reach.

“The role for repellency to provide protection to people from arthropod-borne diseases, such as malaria and dengue fever, was first recognized over 50 years ago; however, spatial repellent products have yet to be fully recommended for inclusion in public health programs. Our team has now been given the opportunity, and the responsibility, to advance these products to those populations in most need — a charge I very much look forward to leading,” said Achee.

Neil Lobo

Neil Lobo

“Spatial repellents may allow us to prevent the spread of disease in places where traditional interventions such as bed nets and indoor residual spraying are not completely effective. We have data that show spatial repellents are effective against insecticide resistant populations, which may have the potential to limit the spread or emergence of insecticide resistance — one of the many challenges faced by public health officials today. Residual transmission is also a significant global concern, and when combined with other tools we expect they will prove to be even more effective,” said Lobo.

“We are grateful for Nicole and Neil’s work that has the potential to transform the lives of millions of people across the globe. Their work is a prime example of fulfilling Notre Dame’s mission to advance knowledge in a search for truth and to be a force for good in the world. We are excited about Nicole and Neil’s work to prove the efficacy of spatial repellents,” said Gregory Crawford, the William K. Warren Foundation Dean of the College of Science at the University of Notre Dame.

“This grant is exactly the kind of research Notre Dame excels in,” said David Severson, director of the Eck Institute for Global Health. “We have a long tradition of leading the world in insect-transmitted infectious disease research with networks all over the globe. Bringing Nicole to Notre Dame to directly collaborate with Neil is an excellent investment the Eck Institute for Global Health can make in support of continuing our collective research at Notre Dame.”

“The Department of Biological Sciences is extremely pleased to be home to this ground-breaking grant to find new ways to combat deadly mosquito-borne diseases on a global scale,” said Gary Lamberti, chair of the Department of Biological Sciences. “We are pleased biology faculty members Nicole Achee and Neil Lobo will lead an international group of colleagues working at sites around the world to develop novel methods to reduce contact between humans and mosquitoes and alleviate suffering for those most at risk.”

Achee and Lobo have formed a collaborative team of multinational researchers and advisers with expertise in malaria and dengue fever who will oversee activities in the field, representing five countries over three continents: South America, Africa and Asia. Their industry partner has dedicated the manufacturing and distribution of the spatial repellent products to the team of investigators.

Site principal investigators include Din Syafruddin of the Eijkman Institute for Molecular Biology and Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Indonesia; Thomas Scott of the University of California, Davis, partnering with NAMRU-6, Peru; Sarah Moore of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute partnering with the Ifakara Health Institute, Tanzania; John Gimnig and Mary Hamel of the Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, partnering with the Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kenya; and Jennifer Stevenson of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, in partnership with the National Malaria Control Centre in Lusaka and the Macha Research Trust, Zambia.

Contact: Marissa Gebhard, 574-631-4465, gebhard.3@nd.edu