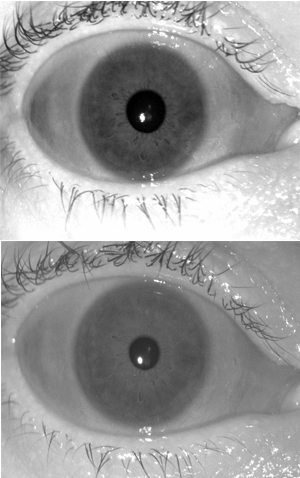

Top: Sample iris image acquired with LG 4000 iris sensor in March 2008. Bottom: Sample image of same iris acquired with LG 4000 iris sensor in March 2011.

Top: Sample iris image acquired with LG 4000 iris sensor in March 2008. Bottom: Sample image of same iris acquired with LG 4000 iris sensor in March 2011.

Since the early days of iris recognition technologies, it has been assumed that the iris was a “stable” biometric over a person’s lifetime — “one enrollment for life.” However, new findings by University of Notre Dame researchers indicate that iris biometric enrollment is susceptible to an aging process that causes recognition performance to degrade slowly over time.

“The biometric community has long accepted that there is no ‘template aging effect’ for iris recognition, meaning that once you are enrolled in an iris recognition system, your chances of experiencing a false non-match error remain constant over time,” said Kevin Bowyer, Notre Dame’s Schubmehl-Prein Family Chair in Computer Science and Engineering. “This was sometimes expressed as ‘a single enrollment for life.’ Our experimental results show that, in fact, the false non-match rate increases over time, which means that the single enrollment for life idea is wrong.

“The false match rate is how often the system says that two images are a match when in truth they are from different persons. The false non-match rate is how often the system says that two images are not a match when in truth they are from the same person.”

Bowyer noted there are several reasons the misconceptions about iris biometric stability have persisted.

“One reason is that because it was believed from the early days of iris recognition that there was no template aging effect, nobody bothered to look for the effect,” he said. “Also, only recently have research groups had access to image datasets acquired for the same people over a period of several years. Recently, another biometric research group (from Clarkson University and West Virginia University) has also published a study that finds an iris template aging effect.”

In their study, Bowyer and Notre Dame undergraduate Sam Fenker analyzed a large dataset with more images acquired over a longer period of time. For one group of people in their dataset, they were able to analyze a year-to-year change over three successive years.

Kevin Bower

Kevin Bower

Bowyer points out that iris recognition is already used in various airports and border crossings, including London airports, Schiphol (Amsterdam) airport, and border entry in the United Arab Emirates. And probably the highest profile and largest application of iris biometrics currently under way is the Unique ID program in India, which has enrolled more people than live in the United Kingdom.

Despite the results of the study, Bowyer does not see them as a “negative” for iris recognition technologies.

“I do not see this as a major problem for security systems going forward,” he said. “Once you have admitted that there is a template effect and have set up your system to handle it appropriately in some way, it is no longer a big deal. One possibility is setting up a re-enrollment interval. Another possibility is some type of ‘rolling re-enrollment,’ in which a person is automatically re-enrolled each time they are recognized. And, in the long run, researchers may develop new approaches that are ‘aging-resistant.’ The iris template aging effect will only be a problem for those who for some reason refuse to believe that it exists.”

Bowyer and Fenker recently presented their research paper at the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Computer Society Workshop on Biometrics.

A copy of the paper is available online.

Contact: Kevin Bowyer, 574-631-9978, kwb@cse.nd.edu