Scientists at the University of Notre Dame studying the presence of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in consumer products and textiles have expanded their search for potential sources of PFAS exposure — developing an effective method of testing for PFAS in drinking water and adding face masks to a growing list of products tested for the toxic class of chemicals.

Known as “forever chemicals,” PFAS do not naturally biodegrade. Studies have shown the chemicals persist in the environment, contaminating groundwater systems, and can accumulate in the bloodstream. PFAS have been linked to reproductive issues, low birth weight, thyroid problems, weakened immune systems and an increased risk of kidney, prostate and testicular cancers.

A new method to measure PFAS in drinking water

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently announced multiple health advisories regarding PFAS in drinking water as part of its strategic roadmap to address PFAS contamination throughout the country. The agency stated that when considering lifetime exposure, “some negative health effects may occur with concentrations of PFOA or PFOS in water that are near zero,” according to scientific findings.

Testing for PFAS at low concentrations has been a challenge, as EPA-approved methods require highly sensitive instrumentation and can be quite time intensive.

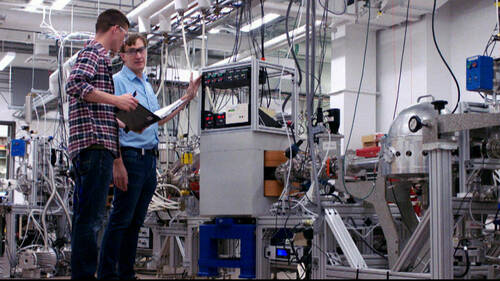

In the laboratory of Graham Peaslee, a physics professor at Notre Dame, researchers have developed a rapid method that can effectively measure all PFAS levels at concentrations as low as 35 parts per trillion using activated carbon felt, gravity filtration and particle-induced gamma-ray emission (PIGE) spectroscopy. This method allows for quick, accurate and cost-effective screening for the presence of PFAS in drinking water.

“The development of a field screening tool to measure the presence of all kinds of soluble PFAS in drinking water rapidly, and at environmentally relevant concentrations, could be a game-changer in terms of identifying which communities are at risk,” Peaslee said.

Face masks do not pose a risk — in most cases

Since the coronavirus pandemic began, face masks have become a common household item. And for many, including health care workers and first responders, they are also a part of the job. In addition to protecting wearers from inhalation of various particulates, some face masks are made for water and heat resistance — and that is what prompted Peaslee and his lab to take a closer look. PFAS chemicals are often used by manufacturers for their water-resistant and film-forming properties, “and we wanted to know if they were being used in personal protective equipment that is in such widespread use,” Peaslee said.

Researchers from Notre Dame, Oregon State University, North Carolina State University and Michigan State University used PIGE testing and other techniques to study a small sample of face masks — only nine in total, including four different types: surgical, single-use disposable masks, N95 masks and reusable cloth masks. One of the masks was specifically marketed to firefighters.

Five out of the nine masks contained some PFAS, but most levels were low enough that the results did not cause concern.

The highest amounts were detected in multi-layered masks made for firefighters. That could add to the risk of exposure firefighters face following studies that found significant amounts of PFAS in personal protective equipment. The chemicals are also known to shed off gear, materials and surfaces — and can be inhaled, ingested or absorbed into the skin.

“PFAS are persistent, toxic chemicals, so we don’t want to find them in face masks,” said Peaslee. “The good news is most people can feel good about the masks they wear and the decision to wear them. Manufacturers of those high-end cloth masks that have higher amounts of PFAS should take action and switch to PFAS-free materials.”

Peaslee’s lab at Notre Dame has found the chemicals in fast food packaging, cosmetics, dental floss, child car seats and firefighting gear, among other products. The results of those studies have led restaurant chains, retailers and manufacturers to seek out PFAS-alternative products.

“These chemicals are still so widely used,” Peaslee said. “We hope these studies help consumers identify products that aren’t a risk, and encourage manufactures that do use PFAS to stop using them.”