Catherine Bolten

Catherine Bolten

When Catherine Bolten first considered studying the city of Makeni in Sierra Leone, many people — government officials, professors, the U.S. ambassador — warned her to stay away. It’s a dangerous and immoral place, they told her, infamous because residents refused to fight the rebels who occupied Makeni for three years (1998-2002) during the decade-long civil war.

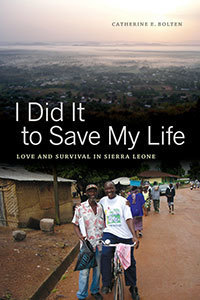

Undeterred, Bolten spent 18 months in Makeni talking to hundreds of people. Her new book, “I Did It to Save My Life: Love and Survival in Sierra Leone,” just published by University of California Press, illuminates a very different kind of community — one in which residents struggled to survive and care for each other within a social order based on love, compassion, material exchange and nurturing.

“Writing this book was an act of balancing the narrative,” says Bolten, assistant professor of anthropology and peace studies at the University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies.

“People in Makeni were making choices that the outside world called ‘inhumane.’ I wanted to show how they found a way to get through horrific circumstances by making alliances that allowed them to survive and feed their families and friends. Far from ‘inhumane,’ this kind of love is proof of humanity, and it is allowing Sierra Leoneans to heal and move on with their lives.”

After introducing the history and culture of Makeni, the book then presents the narratives of seven ordinary people who explain their actions and moral choices during a devastating war. One chapter, for example, titled “I held a gun but I did not fire it,” focuses on David, a schoolboy captured by rebels and forced into a life on the run. In another chapter, “The government brought us death, the rebels allowed us to live,” we meet Kadiatu, a mother who befriends rebel leaders so she can trade looted goods and feed her dying children. Another chapter, “It was the Lord who wanted me to stay,” follows Adama, a widow whose faith becomes an instrument of survival when she preaches to and feeds dying rebels.

What all these narratives have in common, Bolten says, is the Sierra Leonean practice of love. “In Sierra Leone, people use the word ‘love’ to describe long-term reciprocal relationships — putting yourself out there to invest in people’s survival and hope that they do it for you.” The stories, she says, also call into question the government’s own narrative — that Makeni residents openly collaborated with the rebels. Residents argue instead that it was the government’s disloyalty to its people, rather than rebel invasion and occupation, that destroyed the town and forced uneasy co-existence between civilians and militants.

“Ethnographically rich, these accounts come to life in beautiful prose,” writes anthropologist and author Catherine Besteman. “These are inspiring and at times heartbreaking stories. … This will be a valuable contribution as well as a welcome counter to the more popular images of war zones as places of total immorality.”

Originally published by Joan Fallon at kroc.nd.edu on Sept. 21, 2012.