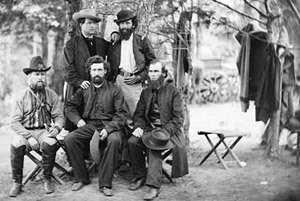

Catholic chaplains of the Irish Brigade, 1862. William Corby, C.S.C. is seated on the right.

Catholic chaplains of the Irish Brigade, 1862. William Corby, C.S.C. is seated on the right.

The events surrounding last week’s football game in Dublin’s Aviva Stadium provided numerous occasions to marvel at the splendidly inextricable relationship between the University of Notre Dame and the land and the people of Ireland.

That relationship was the theme of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism 2012 Hibernian Lecture, given Aug. 30 by Kevin Whelan, Smurfit Director of the Keough-Notre Dame Study Centre, at O’Connell House on Dublin’s Merrion Square. The Hibernian lecture, sponsored by the Ancient Order of Hibernians, annually presents distinguished scholarship in Irish-American history, and this the first time it had been given in Ireland.

Whelan’s ancestry is itself a specimen of the linkage between Notre Dame and Ireland. Brother Aidan O’Reilly, C.S.C., his great-uncle, emigrated to Notre Dame from Bunclody, Wexford, in 1899 to become an influential faculty member and University historian. Whelan, himself a Wexford native, has directed the Notre Dame Study Centre since 1998 and is the author of numerous articles and essays on Ireland’s history, geography and culture. He also has written or edited 16 books, including, most recently, “Notre Dame and Ireland,” a lavishly photographed version of his Hibernian Lecture.

Kevin Whelan

Kevin Whelan

Notre Dame is an American institution with a French name, and when it came to the Irish, the attitude of Rev. Edward Sorin, C.S.C., its founder, was difficult to distinguish from simple bigotry. Nevertheless, Whelan observed, four of the six Holy Cross brothers who arrived with that choleric Frenchman on the south bank of Saint Mary’s Lake in 1842 were from Ireland; Irish women were among the Holy Cross sisters who followed them a few years later; the University’s first two graduates were Irish; and 15 of Father Sorin’s 16 successors as president have been of Irish descent.

Whelan traced the history of the “Fighting Irish” sobriquet past the celebrated football teams coached by Knute Rockne in the 1920s to the carnage of the American Civil War, during which three Notre Dame priests, including Rev. William Corby, C.S.C., served as chaplains to the 69th New York Infantry, also known as the Irish Brigade. When Éamon De Valera, an escapee from British prison who insisted on the title “President of Ireland,” visited the Notre Dame campus in 1919, he laid a wreath before the statue of Father Corby, with a card inscribed “in loving tribute to Father Corby, who gave general absolution to the Irish Brigade at Gettysburg.”

Whelan’s account included other noteworthy links uniting Notre Dame and Ireland, ranging from the campus visits of poets such as William Butler Yeats and Seamus Heaney, musical groups such as U2 and the Chieftains, presidents such as Mary Robinson and Mary McAleese, and Taoiseach Enda Kenny, who last March conferred honorary Irish citizenship on Notre Dame president emeritus Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C.

The thoroughness of Whelan’s lecture notwithstanding, perhaps the most conspicuous evidence of the unique bond between Notre Dame and Ireland was its venue.