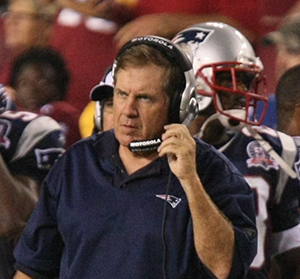

Coach Bill Belichick during an Aug. 28, 2009, preseason game

Coach Bill Belichick during an Aug. 28, 2009, preseason game

“Black Monday” has become as much a part of the National Football League season as Draft Day. The Monday after the last game of the season is marked by the firing of a number of head coaches and the start of a frenetic search for new ones. Many NFL teams searching for a coach rely on “coaching trees” and turn to assistants of highly successful head coaches.

Craig Crossland, a professor of management in the University of Notre Dame’s Mendoza College of Business, and his colleagues studied the NFL to determine if the so-called “acolyte effect” that makes protégés of successful head coaches successful in turn is real. They tracked the career outcomes of almost 1,300 coaches over 30 years.

“Working under a highly successful leader provides initial career benefits in terms of getting a promotion at another organization,” Crossland said. “However, the benefits are short-lived and the long-term effects may even be harmful. We found that acolytes, individuals who had worked under a high-prestige head coach such as Bill Belichick, were 52 percent more likely to be promoted than non-acolytes. This effect was especially strong when the acolyte hadn’t been in the NFL very long, had worked in a small number of teams, or had worked with relatively few other coaches. However, the benefits of the acolyte effect only applied for the first year after the acolyte was away from the famous head coach. Also, when we looked at the eventual outcomes of all promotions, the promoted acolytes actually did worse than the promoted non-acolytes. Whereas 46 percent of the promoted acolytes experienced a positive outcome, which we defined as gaining another promotion or a lateral move, 57 percent of the promoted non-acolytes experienced a positive outcome.”

But do these findings apply when hiring in other fields?

“We think so, but with some caveats,” Crossland said. “In some ways, the NFL is a more conservative test of what we’re looking at. The NFL is an intense, hyper-competitive environment where ‘actual’ performance can be measured somewhat more easily than in many situations. This means that the effects we see are likely to be stronger and last longer in the corporate environment. Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to get good measures of these sorts of things in a large corporate sample. However, we think the basic pattern — initial benefits, but probable long-term drawbacks — should hold.

“For firms looking to hire acolytes, it’s important to consider more than simply the imprimatur of the famous leader that an individual may have worked under. It’s helpful to ask the question: ‘How much of the success that this person has been associated with is attributable to the person and how much is attributable to the leader?’ We also found that the acolyte effect is strongest when there’s the least amount of information about him or her. So, if you’re a hiring manager, you need to do as much homework on the candidate him- or herself.”

The study, coauthored by Martin Kilduff, University College London; Wenpin Tsai, Pennsylvania State University; and Matthew Bowers, University of Texas at Austin, appears in the Academy of Management Journal. An abstract can be found here: http://amj.aom.org/content/59/1/352.abstract.

Contact: Craig Crossland, 574-631-0291, craigcrossland@nd.edu