Mark Schurr is committed to conducting engaged anthropology.

For Schurr, professor and acting chair of the University of Notre Dame’s Department of Anthropology, that means he and his colleagues are dedicated to research that doesn’t just serve academic ends, but can also do good for the world.

At his latest research site — the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie near Joliet, Illinois — Schurr leads by example. Along with postdoctoral research associate Madeleine McLeester, he is pursuing the answers to two critical questions.

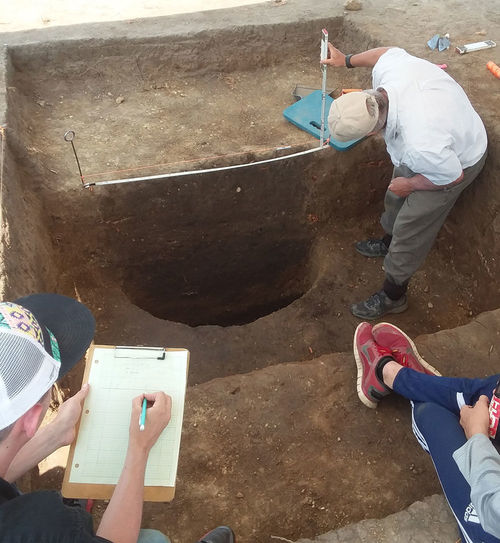

Schurr (top right) takes a measurement during a dig at the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie.

Schurr (top right) takes a measurement during a dig at the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie.

First, they are exploring what life was like for the Native Americans who inhabited the area right before French settlers arrived and began recording history around 1673. And second, Schurr and his team are working to determine how to best restore their research site, a former World War II arsenal, to a natural environment that allows visitors to enjoy and learn from the land.

The former is a standard anthropology research question. The latter aligns the Kankakee Protohistory Project with Schurr’s mission to do engaged anthropology. He hopes that whatever answer he and his team come up with will become a model for environmental reconstruction of natural sites.

“If we can help the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie make this a natural area that will enrich everyone’s life in our region, that would really be our biggest accomplishment,” Schurr said. “I think that’s perfectly in line with Pope Francis’ Laudato Si', the idea of how we should care for the earth.”

In their hunt for answers, Schurr and his team are employing methodologies ranging from the traditional, like month-long summer digs, to cutting-edge, such as thermal imaging cameras attached to drones that can survey huge sites in mere minutes.

Pristine artifacts

Schurr’s current project grew out of his research at the Collier Lodge site in Northwest Indiana, where he led a public archaeology project for more than 10 years.

An archaeology trowel with a variety of artifacts from Schurr’s dig, including small pieces of stone, pottery, bone and shell that help tell the story of what happened at Middle Grant Creek in the prairie.

An archaeology trowel with a variety of artifacts from Schurr’s dig, including small pieces of stone, pottery, bone and shell that help tell the story of what happened at Middle Grant Creek in the prairie.

About three years ago, he and McLeester began looking for a new site that dated to the late 17th century, and found the Middle Grant Creek site at the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie.

“Really, we felt like there’s this period in time right before history that was not only absent from written records, but archaeologically, is really poorly understood,” Schurr said.

So far, Schurr and his more than 100 collaborators — including graduate and undergraduate students, researchers from other institutions and volunteers with the National Forest Service — have found pristine artifacts.

“The preservation is just excellent,” Schurr said. “We even get things like individual fish scales that are still preserved, which you hardly ever see in an archaeological site in the Midwest, because our climate just destroys everything.”

The dark soil is the outline of a storage pit Native Americans used to hold corn, then trash. A deer antler and beaver pelvis are pictured.

The dark soil is the outline of a storage pit Native Americans used to hold corn, then trash. A deer antler and beaver pelvis are pictured.

During their excavations, the team has found large circular storage pits that likely stored corn before Native Americans threw their trash in the holes.

Within these pits, Schurr said his team has unearthed pottery, stone tools, shells, carbonized plant remains, and the remains of animals including turtles, beavers, muskrats and all kinds of fish.

Together, the findings paint a vivid and fascinating picture of life on the site 400 or more years ago.

Innovative techniques

Schurr and a team of Midewin volunteers prepare to conduct a ground-penetrating radar survey, which will give an image of what is buried underground prior to a dig.

Schurr and a team of Midewin volunteers prepare to conduct a ground-penetrating radar survey, which will give an image of what is buried underground prior to a dig.

These discoveries have come as a result of conventional anthropology research methods, namely magnetic surveys and hand excavations of the site. The employment of new technologies, though, sets Schurr’s latest project apart.

Through a collaboration with Dartmouth College anthropologist Jesse Casana, Schurr’s team has used drones equipped with thermal imaging technology to survey the site faster and more broadly than ever before.

Because different materials cool at different rates, these drones can identify buried structures and artifacts, especially at night. At the Middle Grant Creek site, this thermal imaging technology has revealed a large circular structure, which Schurr and McLeester believe is some sort of prehistoric ceremonial enclosure that they plan to research further.

“Every time you use new technology, you can see things in a different way,” he said. “This technology acts as an intermediary between surface-level testing and aerial or satellite surveys.”

Along with a cost-share agreement with the Forest Service, Schurr recently won a Notre Dame Research grant that will fund the Middle Grant Creek project for at least two more years.

He hopes to develop a more complete understanding of the site through continued research, including more undergraduate involvement, all of which will ultimately help with his goal of reconstructing the prairie’s natural environment.

“This was an area that was dedicated to making war,” Schurr said. “And now, we’re trying to convert it to a natural area where people from the Chicago region and the surrounding area will be able to come and enjoy nature, learn about nature, and be refreshed by it.”

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on April 17.