A new food waste system at the University of Notre Dame is poised to reduce nonconsumable food waste on campus by more than 2,000 pounds per day while contributing to the clean energy needs of a local farm — thanks, in large part, to the hard work of several Notre Dame students.

A product of Emerson Electric, Grind2Energy prepares food waste to be converted to clean, renewable energy, reducing waste as well as odors, pests and emissions — all while protecting the environment. Notre Dame is only the second school in the nation to invest in the innovative food-waste recycling system.

“Our implementation of this solution to tackle a large portion of our nonconsumable food waste enables us to take a big step towards meeting our waste diversion goals set as part of our University Comprehensive Sustainability Strategy,” said Carol Mullaney, senior director of sustainability at Notre Dame. “While we continue to work on source reduction and donations of consumable food to local outlets, we will still have food waste and it’s exciting to know that it will now avoid the landfill and be converted into clean energy.”

The University installed the first of three Grind2Energy systems, consisting of a processing sink, grinder and 5,000-gallon outdoor holding tank, at the Center for Culinary Excellence (CCE), part of University Catering, in January.

The holding tank, anchored to a concrete pad, stands about 15 feet tall. It is heated from the inside to keep the contents from freezing. A heated cover also helps to insulate the tank from the cold. That includes the recent polar vortex, which saw temperatures drop well below zero.

When it’s time to empty the tank, a septic hauler attaches a hose to a valve at the bottom of the tank, pumps the waste into a septic truck and then transports it to a local farm where it is converted to energy. Excluding transport, the process takes about 20 minutes. A “seed” of waste is left behind in the tank as a starter for the next batch of slurry. Noise and odor are minimal.

The waste counts as a donation to the farm, though it saves the University money in the form of lower trash costs.

Two additional Grind2Energy systems will be installed in the North and South dining halls in the near future.

Combined, the three systems will reduce nonconsumable food waste from the dining halls and CCE by 99 percent, according to Allison Mihalich, senior program director in the Office of Sustainability. They will reduce overall waste, campuswide, by 10 percent, or 700,000 pounds per year. That’s waste that otherwise would combine with other trash to produce methane, a potent greenhouse gas, in local landfills.

Campus Dining previously partnered with LeanPath, a global food-waste service, to reduce pre-consumer food waste related to overproduction, spoilage, trimmings, overcooking or contamination by 30 percent across both dining halls and the Center for Culinary Excellence.

“We’re excited to partner with our colleagues from the Office of Sustainability in the introduction of Grind2Energy at Notre Dame,” said Chris Abayasinghe, senior director of Campus Dining. “Campus Dining is able to divert a significant amount of food waste from the local landfills. The compost generated from the units enables us to enjoy upstream and downstream benefits by combining technologies in LeanPath and Grind2Energy. We look forward to completing a successful rollout at North Dining Hall and South Dining Hall over the next few months.”

The project, which is part of an ongoing effort to improve sustainability campuswide, is a collaboration among Campus Dining, the Office of Sustainability and Homestead Dairy, a state-of-the-art dairy farm spread across multiple facilities in Plymouth, Indiana, about 30 miles south of Notre Dame in Marshall County.

What’s more, it is the direct result of research into the problem of food waste on campus by Notre Dame junior Matthew Magiera, a chemical engineering major from Pittsford, New York, who interned in the Office of Sustainability all of last year.

Among other things, Magiera recommended digesting such waste because of the lack of available space, not to mention ingredients, for composting on campus, as well as the lack of a use for the end product: tons upon tons of fertilizer.

In doing so, Magiera built upon the research of previous undergraduate students and worked with Mihalich to evolve that research, along with his own insights, into a workable solution.

“The question became can we compost at all? And if we can’t, what can we do?” said Magiera, who will spend the summer interning in the environmental division of Anheuser-Busch, the largest operator of anaerobic digesters in the world.

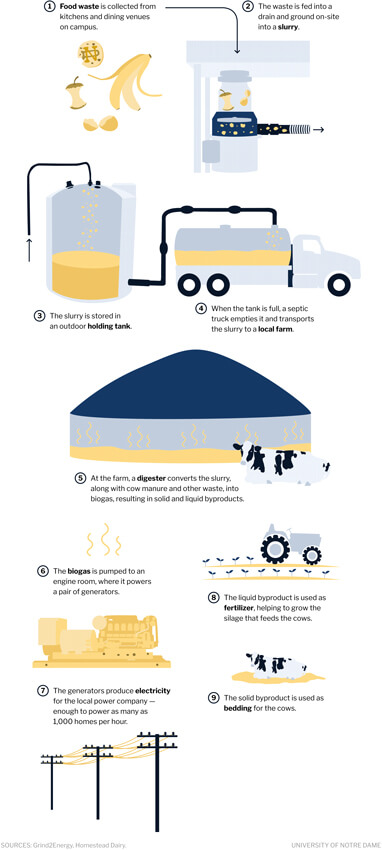

This is how it works:

Organic waste, including food scraps as well as fats, oils and grease from CCE and the dining halls, is ground on-site into a slurry and then transported to Homestead. There, it is converted to energy via anaerobic digestion, a process in which microorganisms break down organic matter to produce biogas, a methane-rich gas that can be combusted to produce energy or heat or processed into other fuels, such as natural gas.

The process results in byproducts that can be used in fertilizer or as animal bedding, leaving little waste behind.

“It is almost a closed-loop, zero-waste process for the farmers,” said Magiera.

Certain types of mollusks, such as mussels, are not compatible with the system, Mihalich said, because of their hard shells. Egg shells, however, as well as shrimp and other soft-shelled crustaceans, are OK.

Homestead already converts cow manure and so-called “co-feeds” — calf bedding, day-old feed, fats, oils, grease, organics, food waste — into electricity at its facilities in Plymouth, which host about 3,500 cows. The farm also grows silage for the cows.

A series of three digesters, each with a capacity of 950,000 gallons, converts the manure and co-feeds to biogas, which is then piped to a nearby engine room and used to power a pair of generators that produce electricity for the local power company — enough to power as many as 1,000 homes per hour.

“If you really look at the cycle, what we do as far as feeding the cows, growing the crop, producing energy off the manure and then using the manure as fertilizer to regrow the crop, that’s a pretty awesome green cycle,” said Ryan Rogers, co-owner of Homestead.

Food waste is an increasing problem nationwide. Currently, about 40 percent of the food in the U.S. is lost or wasted annually, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation and depletion of freshwater resources. College campuses produce an estimated 22 million pounds of food waste annually through their dining operations alone, according to the Food Recovery Network.

Notre Dame is no exception.

Currently, food waste accounts for about 10 percent of all waste on campus, Mihalich said. That’s despite the University partnering with Cultivate Culinary, a local food rescue organization, and Food Rescue US to rescue unserved food from campus dining halls and athletic venues, including Notre Dame Stadium, Purcell Pavilion and Compton Family Ice Arena. Campus Dining has also switched to smaller trays in the dining halls to encourage students to be more selective, and thus less wasteful, in their food choices.

As a complement to other food waste programs on campus, Grind2Energy represents a step forward for the University on its journey toward sustainability. It also contributes to the University’s growing reputation as an eco-friendly school, a label it shares with Harvard, Stanford, Northwestern and Ohio State, among others.

For more information about Notre Dame’s sustainability practices and goals, visit green.nd.edu.

Contact: Erin Blasko, assistant director of media relations, 574-631-4127, eblasko@nd.edu