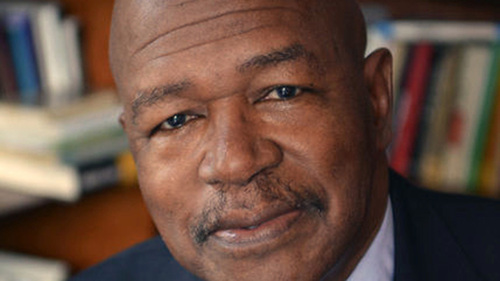

The Institute for Educational Initiatives at the University of Notre Dame hosted Elijah Anderson, the Sterling Professor of Sociology and of African American Studies at Yale University, via Zoom on Friday (Feb. 4) for a conversation about his new book, “Black in White Space: The Enduring Impact of Color in Everyday Life.”

Chloe Gibbs, director of the Notre Dame Program for Interdisciplinary Educational Research and assistant professor of economics, welcomed attendants and introduced Anderson, saying, “I have the great pleasure of introducing today’s speaker, Dr. Elijah Anderson, an eminent sociologist, urban ethnographer and cultural theorist. Dr. Anderson is the author of and editor of several books, including most recently ‘Black in White Space: The Enduring Impact of Color in Everyday Life,’ which was released this week.”

Anderson, a South Bend native, started the lecture by describing what an ethnographer is. “Ethnography is defined as the systematic study of culture, of people, doing things together. The ethnographer is concerned with trying to apprehend, comprehend and understand local culture and local knowledge.”

He explained that this is important because most people are ignorant about other people, so an ethnographer’s work is to try to minimize the gap in the understanding of others.

Anderson said that for people to understand race today, they have to consider slavery. “Slavery established Black people at the bottom of the racial order. This is key.”

Continuing through to the civil rights movement, Anderson said the government initiated a racial incorporation process, by which large numbers of Black people made their way into settings that were white, from urban ghettos in rural areas into settings previously occupied only by white people.

“Their reception in these settings, these white settings or previously white settings, has been mixed. Many white people were supportive, tolerant; many others felt that the inclusion of Black people abrogated their own rights,” he said.

Anderson said that we still live in a segregated society, not by law, but by custom, preference and practice. “White neighborhoods, schools, universities, workplaces, restaurants and other public spaces persist segregated. Black people perceive these settings as the white space, which they consider to be informally off-limits to people like them.”

He then pointed out that white people typically avoid Black space, while Black people are required to navigate white space as a condition of their existence. “This is important because then you get a sense of white space as a perceptual category, but it’s undeniably so, just as Black space is undeniable.

“In the white space the white person has implicit power over Black people, even if they’re supposed to be the same status,” Anderson said. “Therefore, Black people approach white space and the white people they find there with a certain amount of care. There’s a certain tension there as Black people navigate white space. Black people need anonymous white people in the white space who treat them well, who treat them with respect.”

Anderson’s book was informed by analysis based on fieldwork, talking to Black and white people in Philadelphia. His findings have important implications for the “seemingly intractable racial disparities in our society, especially persistent poverty,” he said.

Gibbs asked Anderson if there are things people could do to break up the power stronghold among historically privileged groups on institutions such as higher education.

“Institutions really have to do better. I think the start is to recognize these issues that Black people have in these spaces, and to double down on supporting the Black students,” Anderson said. “In fact, one of the biggest ways people can help would be by increasing the number of Black students, increasing the number of Black professors and increasing the number of courses that are relevant to Black people and their existence. And teaching the white people about this, because a lot of white folks are ignorant of Black history.”

Answering a question about managing exhaustion experienced by being on high alert as a Black person in a white space such as a university, Anderson said, “It’s tough to be the only Black person. My feeling is that the universities should be doing all they can with their resources to make life more comfortable for these students.

“These are not simple issues, they’re tough issues. I think that race is one of our toughest issues as Americans; we really have to get beyond it,” Anderson said.

Throughout the month of February, Notre Dame will host a number of events to celebrate Black History Month. A list of events can be found here.