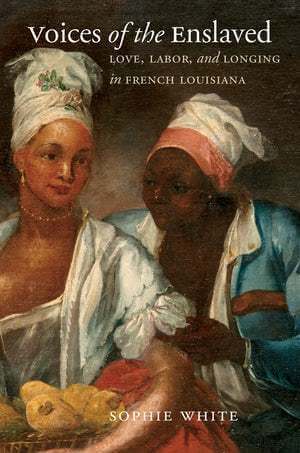

Sophie White, a professor in the University of Notre Dame’s Department of American Studies, has won the prestigious 2020 Frederick Douglass Book Prize for her work “Voices of the Enslaved: Love, Labor, and Longing in French Louisiana.”

The prize, sponsored by Yale University’s Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, recognizes the best book published in English on slavery, resistance or abolition. It is considered one of the most distinguished awards for the study of global slavery.

Established in 1999, the prize is named for Frederick Douglass, the onetime slave who escaped bondage to emerge as one of the great American abolitionists, reformers, writers and orators of the 19th century.

White will receive the award in an online celebration on Feb. 23.

“This is a very special award — and a sobering reminder of how much work still needs to be done on slavery and its legacies,” said White, a concurrent professor in the Department of Africana Studies, the Department of History and the Gender Studies Program. “'Voices of the Enslaved’ brings to light an extraordinary archive in which the enslaved testified and their words were recorded. I am deeply honored that this work has resonated so widely, and I am grateful for the visibility that the Douglass award offers in bringing the lives of these individuals to new audiences, allowing them to speak for themselves, and allowing us to hear their voices and to listen to what they had to say.”

The prize is the latest in a series of accolades White has garnered for the work. She also recently won the James A. Rawley Book Prize from the American Historical Association, the ASWAD Rosalyn Terborg-Penn Prize for Outstanding Book on Gender and Sexuality, and the Mary Alice and Philip Boucher Book Prize in French Colonial History, in addition to several earlier awards.

White wrote “Voices of the Enslaved” with support from a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities, her second such award. In the book, she offers an exceptional glimpse into the lives of enslaved people — through their own words — by analyzing courtroom testimony from enslaved Africans in French colonies, primarily in 18th-century Louisiana but also in islands in the Caribbean and Indian Oceans.

“Sophie’s book is a remarkable work of scholarship, and it is exciting to see it receive a tremendous level of recognition from the academic community,” said Sarah A. Mustillo, the I.A. O’Shaughnessy Dean of the College of Arts and Letters. “Through her research, she has amplified important voices that have rarely been heard — something we must do more often if we are to address complex problems facing society.”

Individual slaves did not often have an avenue to tell their life stories, White said, because they were typically denied access to literacy and because slavery attempts to strip the enslaved of their identity and individuality.

But when called to testify in court — as defendants, witnesses or victims — the enslaved had a rare public forum.

“In French law, testimony and confession are key,” she said. “In these trial records, there is extensive questioning, and I argue that there is a lot of room for slaves to intersperse other information and to give us a sense of who they are or who they would like to project they are to the court.”

Many slaves seized the opportunity and sought to voice their experiences of slavery and removal from their homelands. Court clerks often acknowledged these moments in their transcriptions, White said, as they commented that a slave witness “said, without being asked,” or that a slave defendant “said on her own initiative.”

“It is no longer about the court case,” she said. “It becomes about other things they want to share, which is what makes this interesting and riveting. This testimony is forced; they have no choice but to appear. But, in spite of that constraint, there is still the potential for an autobiographical narrative.”

Jane Landers, the jury chair for the Frederick Douglass Book Prize, said “Voices of the Enslaved” is a deeply researched and beautifully written book that paints a “global picture of the intimate lives of enslaved people.” The prize committee also praised the book for bridging the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, thereby making a significant contribution to understanding both North American continental and transnational histories.

David W. Blight, director of the Gilder Lehrman Center, added that White’s detailed exploration of the testimonies of a variety of actors within the French imperial world made “the notion of the past as a foreign country,” which we can visit through historical research, come alive.

White is developing a digital humanities website related to the project, called “Hearing Slaves Speak in Colonial America,” which will provide, side-by-side, an image of the original court manuscript page, a transcription of the French, and her translation into English. It will be featured in the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture’s OI Reader.

“Because I could only write in depth in the book about eight individuals — though many, many others appear along the way in the various chapters — I wanted to develop a website that could showcase some of the other trials,” she said. “By including the entire trial transcript in this manner, I hope that it can become an effective teaching tool and that it will also be of interest to the lay reader.”

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on Dec. 10.