For centuries, the official history of Ireland was held in British archives, and the unfiltered Irish perspective was lost — except in its poetry and folk songs.

For that reason, among others, poetry holds a higher status in Irish culture than in many other countries, said Brian Ó Conchubhair, an associate professor of Irish language and literature at the University of Notre Dame.

“Poetry has always been associated with Ireland. Our current president is a poet,” Ó Conchubhair said. “But historically, poetry is Ireland’s unofficial archive. While the printed records are the British account of what was happening, the poetry and the songs show what’s missing, what’s been left out of the official history. They give us an underground, hidden perspective on Irish history and culture.”

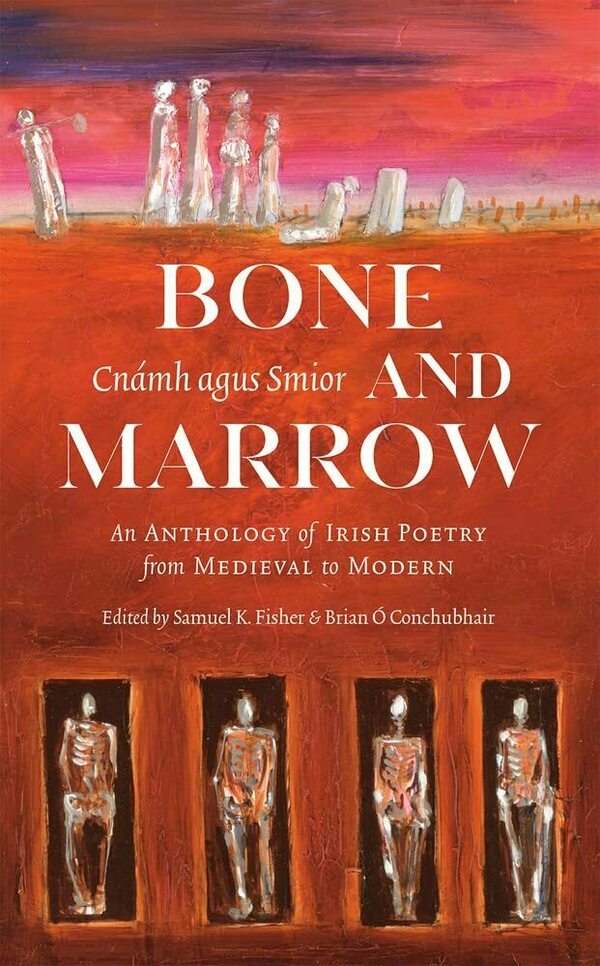

Ó Conchubhair and co-editor Samuel Fisher, an assistant professor at the Catholic University of America, are bringing that history to a wider audience in the most comprehensive collection of Irish poetry to date, “Bone and Marrow/Cnámh agus Smior: An Anthology of Irish Poetry from Medieval to Modern.”

“Bone and Marrow,” to be released on St. Patrick’s Day (March 17), is printed in Irish and English side-by-side. It traces Irish history from the sixth century to the present day and is the first anthology of its kind since the 1980s.

“There have been new debates, new arguments since then, and the canon has shifted,” Ó Conchubhair said. “Ireland has gone from the Troubles, the IRA and the peace process to the Celtic Tiger economic boom, and what is considered the best Irish portrait has changed. We wanted to create a text that reflected that.”

Ó Conchubhair and Fisher, who completed a doctorate in history at Notre Dame, divide the book into historical periods focused on significant events — including the monks’ arrival in Ireland, the medieval era, the first arrival of the English, the famine, World War II and the present day. One of the book’s final poems addresses the COVID-19 pandemic. The editors also offer readers a brief introduction to each poem and an essay at the beginning of each chapter, contextualizing its poems and songs.

“A lot of the poems are very political and sectarian and quite violent — you have the Vikings. You have the revolutions. You have the famine, wars and songs of immigration,” Ó Conchubhair said. “And then there are funny poems in there. There are poems on love, the environment and injustice. The breadth of the collection is one of the things that makes it so distinctive.”

The book’s title is inspired by a quotation from 17th-century Irish historian Geoffrey Keating, who said that the bone and marrow of Irish history was to be found in poems.

It is by design, Ó Conchubhair and Fisher suggest in the book’s introduction, that Keating chose a phrase that was both “poetic and precise.”

“To say poems were ‘bones’ was to say that they were the frame of history, gave it its shape, formed an inescapable frame of reference, were as hard and solid a fact as one’s own skeleton,” they wrote.

But poems were not only bones. They were marrow — they were alive, creative, producing new things.

“We offer this volume up, then, not only to students and scholars of Irish literature or the Irish language but to anyone who might like to be commenting not only on Ireland’s past but also its present and future,” Ó Conchubhair and Fisher wrote. “We hope they will find here some useful authorities for doing so; and, more importantly, that they will have the pleasure of discovering, over and over, the delightfully surprising reality to which all of these poems witness: The thing goes on. The bones are alive.”