When shipping products across the ocean, ships must take in large amounts of ocean water, known as ballast water, to help improve stability throughout travel. As cargo is loaded or unloaded, the volume of ballast water must be adjusted, and often aquatic species are taken in or let out with the ballast water. Unfortunately, this can lead to the spread of non-native species throughout various ports as ships take in ballast water at one location and discharge it at another.

New research from the University of Notre Dame, together with colleagues at Cornell University and Governors State University, mapped oceanic shipping patterns to see how the Arctic could be affected by non-native species introduced by ballast water. This is especially relevant as climate change is increasing water temperature, potentially allowing non-native species to thrive in a location where they were previously less likely to survive.

“Modeling and tracking shipping patterns from port to port is important for considering policies that would best prevent an invasion of non-native species,” said Nitesh V. Chawla, co-author of the study, the Frank M. Freimann Professor of Computer Science and Engineering and the founding director of the Lucy Family Institute for Data and Society at Notre Dame. “This is a major threat in Arctic ecosystems as shipping increases due to Arctic ice melting, thus revealing new routes, allowing for more human activity and increasing the risk for invasive species.”

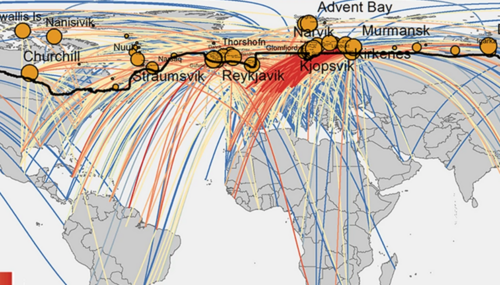

Researchers mapped shipping patterns from around the world into the Arctic as well as routes taken within the Arctic over the span of 15 years. By doing so, researchers identified potential species introduction pathways, species dispersal pathways and the overall risk of species introduction into the Arctic. Based on the models developed for the study, which was published in Nature's Scientific Reports on Nov. 11, the research showed the Arctic is only adding more traffic, but not all ports are increasing traffic evenly. Instead, certain ports are seeing the most traffic and are “hubs,” potentially further spreading harmful species.

“Because we know the majority of shipping traffic is mostly concentrated at specific ports, our research suggests that current global shipping policies may not be enough to limit non-native species introduction to the Arctic,” said Mandana Saebi, lead author of the study and a graduate student in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at Notre Dame. “We recommend the consideration of additional port-based policies so that there can be targeted strategies for mitigating environmental concerns to the ports most at risk.”

In addition to port-based policies at hubs for non-native species management, the study proposes prioritizing certain locations for surveillance of non-native species as well as choosing potential hubs to house new ballast water treatment facilities.

“Our results add to the increasing evidence that climate change is increasing the risk of ship-borne invasions in the Arctic, and could inform the development of more effective management strategies to prevent future invasions in the Arctic and beyond,’’ said study co-author David Lodge, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and the Francis J. DiSalvo Director of the Atkinson Center for Sustainability at Cornell.

Additional co-authors on the study include Jian Xu and Salvatore R. Curasi at Notre Dame and Erin K. Grey at Governors State University. Lodge is the former director of the Notre Dame Environmental Change Initiative. The research is funded by the Army Research Laboratory, a Jefferson Science Fellowship from the U.S. Department of State to Lodge, and the National Science Foundation. The study evolved from a course from the U.S. Department of State Diplomacy Lab.

To read the full study, visit https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-76602-4.

Contact: Brandi Wampler, research communications specialist, Notre Dame Research, brandiwampler@nd.edu, 574-631-8183; research.nd.edu, @UNDResearch

Originally published by at research.nd.edu on Dec. 15.