So you want to write about libraries?

Double Octuple Newspaper Web Perfecting Press, 1903

In the Library with the Lead Pipe is a little over a year old now. We published our first article on October 8, 2008, and we’ve now published thirty-five in all, along with five group posts. By most measures, we’re still a new publication, but we’ve also been pretty successful. About 2,250 people subscribe to our feed, we were one of the LISNews blogs to read in 2009, we’re indexed in LISTA, and many of our favorite writers and librarians have contributed articles or read drafts of our work, mentioned us on their blogs, left comments, or encouraged us in person.

In this article, I do my best to explain why we think we’ve been able to reach people. Although it’s hard to avoid talking about ourselves in an article that describes our experience writing, editing, and publishing In the Library with the Lead Pipe, our motivation is to encourage our readers to produce their own experiments, not to encourage them to adopt our model. When we created In the Library with the Lead Pipe, we had to figure out a lot of things for ourselves. Because we love reading good writing about libraries, we’re sharing what we know in the hope of bringing more good library writing into the world.

Assemble a Team

Treadwell’s Wooden-Frame Bed and Power Press, 1822

Writing, at least writing that’s intended for publication, is an odd mix of the solitary and the social. You spend time alone, reading and thinking, working through your ideas and trying to present them in a way that resonates for other people. And then you share a draft of your work, ideally with someone you trust, and that person edits your text, refines it, makes suggestions, helps bring out the best in you. Our writing is only as good as our relationship with our readers, both the editors who help us turn our drafts into publications and the readers who spend time with our thoughts after they’ve been published, just as you’re doing now.

We publish most of our work at In the Library with the Lead Pipe over solo bylines, but all of our posts are group efforts. We usually bounce ideas off of each other before we get heavily involved in any research, and we rely on each other’s differing perspectives and skill sets as we refine our articles and prepare them for publication. We divide the tasks involved in keeping a blog/journal on schedule and have learned together what’s involved in this kind of undertaking. There are probably more small compromises involved for us than there are for people who publish solo, but none of us compromise on the things we care most about, such as open access and productive collaboration. We all feel comfortable disagreeing with the group and suggesting alternatives, and we all value unanimity when possible (or absolutely necessary), but are fine with simple majorities most of the time. We also enjoy co-authoring group posts, such as “What Not to Do When Applying for Library Jobs,” because they allow us to collaborate even more fully than we can in our solo posts, enabling us to include multiple perspectives in a single article.

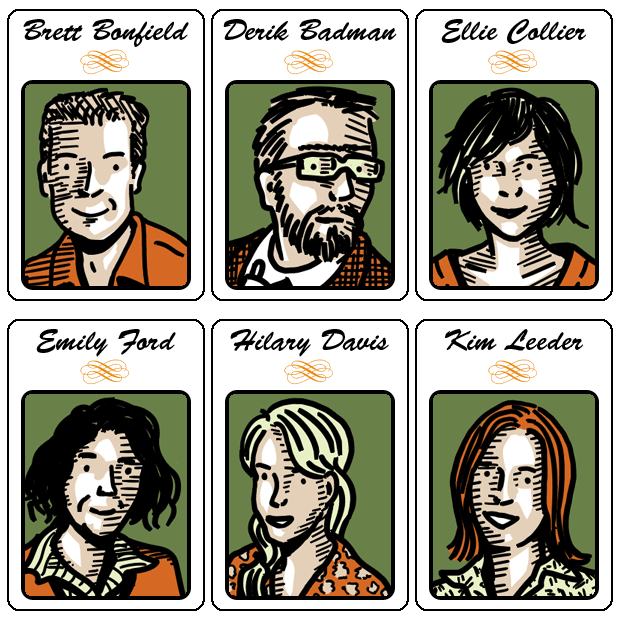

The team behind In the Library with the Lead Pipe was assembled at the 2008 ALA Annual in Anaheim. Over lunch, Kim Leeder and I were talking about how much we would miss being first-year academic library bloggers at ACRLog. She was also eager to create an outlet for the enthusiastic, creative, and occasionally revolutionary voices she had been hearing as a participant in the 2008 ALA Emerging Leaders program. Kim suggested that we put together a group of librarians and start our own publication. Our goal was to find other people who seemed likely to bring out the best in each other, like the groups who publish ACRLog, Library Garden, and Pop Goes the Library.

Kim had worked with Emily Ford on an ALA Emerging Leaders project. I had worked with their fellow Emerging Leaders Derik Badman at Temple University and Ellie Collier on an ACRL panel. Being a North Carolina State University Libraries fanboy, I approached Andrew Pace for a recommendation from NCSU and he encouraged us to recruit Hilary Davis. It’s frightening to ask people to commit to a new project that may take up a lot of their time, especially when you don’t know them well, but know enough to know how busy they are. Fortunately, everyone agreed almost immediately even though we knew we were entering an area of the publication market that often seems saturated.

Find Your Niche

Modern Delivery Van for Grocers, Druggists, Etc.

As Walt Crawford has documented, at any given point there are approximately 500 active, fairly widely read library blogs. Additionally, there are dozens of non-blog library publications, such as Public Libraries or Library Resources & Technical Services. The world certainly didn’t need another new library publication last year any more than it needs one this year, but we figured we would be all right if we created the kind of publication that would hold our interest as readers. What librarian isn’t always on the look out for a good new read?

Our initial idea, our elevator speech, was simple: “We want to be the NPR or New Yorker of library blogs. We want to combine the intellectual rigor of an academic publication with the readability of The New Yorker or the storytelling of NPR.” This was a huge improvement over my initial attempt to get this idea across, which I’d written about in a piece for ACRLog with embarrassing results. The useful thing about mentioning NPR and The New Yorker is the mystique they carry. NPR is known for its personalities, its tendency to make you care about topics you don’t find intrinsically interesting, and its driveway moments—its ability to make you sit in your car and listen to the end of the story even after you’ve reached your destination. The New Yorker is known for its writers—even people who, like Garrison Keillor, have written for The New Yorker, write novels in which they fantasize about writing for The New Yorker—and also for its credibility: no one takes copyediting and fact-checking more seriously. If we can make In the Library with the Lead Pipe into a publication people look forward to reading and good writers want to write for, if we can be compelling and accurate, we’ll be happy with what we’ve created.

Our elevator speech itself, though compelling enough for our needs, wasn’t strictly accurate. Publications like Library Journal and American Libraries probably have more in common with NPR or The New Yorker than we ever will, but our intention is different from theirs. For one thing, like the stories on NPR and the articles in The New Yorker, we want our posts to be as compelling for people in other fields as they are for librarians. I regularly read articles or listen to podcasts by people discussing economics, philosophy, medicine, and software start-ups, in part because I’ve developed an interest in these topics, but mostly because I like how they think; I consistently get ideas from these writers and broadcasters that apply directly to my library work. What these publications have in common is, like Meredith Farkas’s Information Wants To Be Free and Wayne Bivens-Tatum’s Academic Librarian, they take on broad ideas that benefit from being explored at length. I can imagine economists, philosophers, medical practitioners, and start-up founders developing an interest in libraries, and those who do would probably enjoy learning about our field by reading Meredith’s and Wayne’s long form posts. For us, writing long form posts—limiting ourselves exclusively to articles and essays whose lengths vary between about 2,000 and 5,000 words—made sense because we thought it could broaden our appeal.

Long form work also lends itself to intellectual rigor. We were inspired by open access journals like Evidence Based Librarianship, First Monday, and especially The Code4Lib Journal, whose modified peer-review model we further modified. In our version of peer review, each piece is read before publication by at least one external reviewer and at least one Lead Piper. We encourage writers to choose reviewers with high standards, people who will reject substandard or unclear ideas or phrases. I think of our process as being more like a thesis review committee than like blind review, especially because we’ve never had a completed article rejected. From a scholarly publishing perspective, it feels a bit more like a compressed thesis/dissertation process.

Initially, we propose ideas to each other. Some ideas are rejected before they’re turned into articles, others are encouraged. After writing what we believe are polished drafts, we share our articles with outside reviewers. Sophie Brookover could have scuttled my review of her book; she didn’t, but she did make significant changes to portions of it, as did Meredith Farkas, my other outside reader for that piece. I got the same sort of editorial guidance from Tim Spalding and Aaron Swartz, who agreed to read my second piece. Either one of them could have objected strongly enough to elements of my article that the entire thing would have had to be rewritten or abandoned, and both made important suggestions the led to significant modifications. After incorporating ideas from our external reviewers, we show our revised drafts to each other. Again, in most cases this leads to significant changes to our articles before they’re published.

A key element in our philosophy is that articles which offer criticisms also offer constructive solutions. That first part is important to us—we place a high value on identifying problems in the status quo, we intentionally try to shake things up a bit, and we’re comfortable with a bit of irreverence and humor—but we won’t publish any critiques that aren’t accompanied by what we consider a useful solution. Thus, our name: In the Library with the Lead Pipe, which was inspired by the game, Clue, as was our tagline, “The murder victim? Your library assumptions. Suspects? It could have been any of us.”

The peer review process isn’t limited just to the Lead Pipe team: like ACRLog, which gave me an opportunity to post an article as a guest author before I was brought on board as a first-year blogger, we encourage people to submit their work for consideration, and also make it a point to recruit articles by people whose work we know and like. Having guest authors lets us cover areas we care about but don’t have the expertise to write about on our own, and it gives us a chance to work with a broader range of writers and include other perspectives. It also gives our guests a platform without requiring them to take on the editorial and other responsibilities required to keep In the Library with the Lead Pipe on course. Guest authors still need to recruit external and internal reviewers, they still need to learn their way around our publishing platform, and they are required to submit a short bio along with their article. The idea is that submitting an article shouldn’t be any harder or easier for our guests than it is for us.

In finding our niche and developing our processes, we did our best to find the things we liked and admired in other publications, and we adapted them to suit our skills and personalities. I don’t think the world needs another In the Library with the Lead Pipe, but I’d love to read a new publication whose writers go through a similar process of picking and choosing their favorite elements from the publications they enjoy reading.

Build a Sound Foundation

Accurate Measurements are Essential to Correct Time Keeping

I recently read an interesting explanation of the request that Van Halen included in its legendary backstage concert rider: “M & M’s (WARNING: ABSOLUTELY NO BROWN ONES).” According to The Smoking Gun:

While the underlined rider entry has often been described as an example of rock excess, the outlandish demand of multimillionaires, the group has said the M&M provision was included to make sure that promoters had actually read its lengthy rider. If brown M&M’s were in the backstage candy bowl, Van Halen surmised that more important aspects of a performance—lighting, staging, security, ticketing–may have been botched by an inattentive promoter.

I think the same idea applies to publications. There’s no direct correspondence between good writing and either registering your own domain name or creating a unique layout, but at this point I almost always skip past writers who haven’t bothered to take control of their identity. Purchasing a domain, such as inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org is simple, and you can own one for less than $10 per year. It’s a good idea to register your domain with an ICANN-accredited registrar: I recommend Namecheap or Gandi.

Registering a domain is not the same as self-hosting your publishing software. All of the interesting hosted platforms allow you to associate your own domain with their servers. However, even though Google’s Blogger, WordPress.com, Tumblr, and Posterous are reliable, usable, and free, I still recommend that you sign up for a web host and run your own software. Again, it’s about making your site better for your users and, though there’s an initial learning curve, you’re able to get a lot more done with a lot less hassle.

Selecting a web host can seem daunting because there are thousands to choose from and most appear to be fairly indistinguishable from one another. My recommendation would be to go with an inexpensive plan from Blue Host, DreamHost, NearlyFreeSpeech.NET, or A Small Orange, four of the hosts featured in Lifehacker’s January 2009 survey of the Most Popular Reliable and Affordable Web Hosts, or with LISHost. This is a somewhat larger commitment than registering a domain. There’s more involved, and the price will vary between approximately $25 and $120 per year, depending on your needs. I feel strongly that your time, and your readers’ time, is more than worth it.

One of the primary advantages of using a web host is that it gives you control over the software you run on your website. For us, the decision to use WordPress to publish In the Library with the Lead Pipe was an easy one. We were already familiar with it, it’s stable, it’s regularly updated and easy to upgrade, and it’s very good at reducing spam. It also has an extensive range of sophisticated plugins; though we actively weed any we aren’t using, we currently depend on twenty-nine plugins to help us present information, manage our data, and collect statistics. That last part, statistical measurement, is especially important: while Google’s Analytics and FeedBurner can be useful, it’s nice not to be reliant on third-party vendors for something so important. We’ve used Analytics from the beginning, but we’ve chosen not to use FeedBurner to measure our feed statistics. Instead, we use WordPress plugins Feed Statistics and StatPress Reloaded. Neither plugin has been updated in a while, but both still seem to be working fine.

WordPress also made it fairly simple for Derik to create a unique website design. By modifying an existing template and adding in his art, Derik gave us some of the best staging in online library publishing. When you visit a website for the first time and see original art, it immediately signals to you that the site’s creators care about your experience.

Six Librarians, drawing by Derik Badman

Go to Your Audience

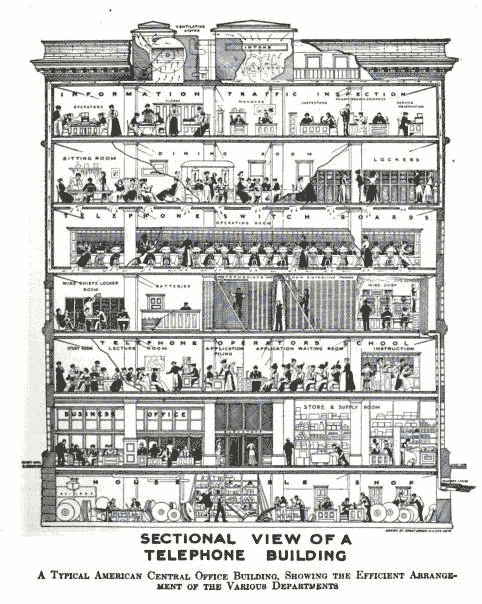

Sectional View of a Telephone Building: A Typical American Central Office Building, Showing the Efficient Arrangement of the Various Departments

In addition to making sure our site’s appearance made our content more appealing, we wanted to make sure our site’s content license was appealing as well. We wanted a license that was permissive enough to make our content as usable as possible, but we didn’t want it to be so permissive that it would be hard for us to attract guest authors: Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 seems to strike the right balance. As a measure of thanks for Creative Commons for creating this license, any royalties we make as part of our arrangement with EBSCO to appear in LISTA, though likely to be modest, will go directly to Creative Commons. Our license and modified peer review policy also qualify us as open access, which helped us get a nice boost in readership early on when Peter Suber’s SPARC Open Access Newsletter linked to us.

The other decision we made early on that’s helped us was the choice to apply for an ISSN. Unlike ISBNs, which cost about $125 for one and $275 for a block of ten, you can request an ISSN for free and you can start the application process before you publish your first issue. An ISSN is the major requirement for appearing in indexes, which was one of our goals. We aren’t going to change our policies in any major ways in order to get indexed—we’re happy with our version of peer review, and we don’t plan to divide our content into volumes and issues—but we still want people searching for articles in academic databases, such as those offered by H.W. Wilson or ProQuest, to find our articles in their search results.

I found it surprisingly difficult to figure out the relevant indexes’ collection policies or what we needed to do in order to submit our work for consideration. Here’s a short guide for others who might want to go this route. I recognize that it seems mundane, but a guide like this one would have saved me ten or twenty hours and a great deal of frustration:

- Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). We felt that we met DOAJ’s selection criteria, so we submitted our application online on December 9, 2008. The next day, we received a very nice rejection note from a reviewer in Sweden who had been a subscriber nearly from day one. As she explained, “For a journal to be included in DOAJ, the content of each issue, have to be at least 1/3 original research. Translated into blog publishing, I would say that means one issue = one month. So if you publish four posts in one month, at least two have to be original research… We are a bit traditional in the sense that we typically expect scholarly journals to have an abstract, a purpose of the paper clearly stated, references etc etc. Please do suggest the journal again if you feel that the content has shifted in this direction.”

- ERIC. We realized this was a stretch, but we felt we were close enough to meeting ERIC’s criteria that we emailed our information to ericpub@csc.com on December 9, 2008. We received a nice confirmation on December 15, 2008 from a Content Development Assistant, but haven’t heard anything since.

- Google Scholar. When we first submitted In the Library for Google Scholar’s consideration, the process involved sending an email to scholar-publisher@google.com, which we did, but we never received a response. The process has since been updated and a new request was submitted on November 22, 2009.

- Informed Librarian (subscription required). We submitted our request to be included in Informed Librarian on December 26, 2008, were notified of our acceptance on January 7, 2009, and received a note on June 4, 2009 that coverage had commenced.

- INSPEC (subscription required). We couldn’t find information on INSPEC’s website regarding submission contacts or collection policies, so we sent a message to its publishing contact on December 9, 2008. The message wasn’t confirmed and we have never been contacted by INSPEC.

- ISI (subscription required). Another stretch, but we thought people searching the Social Sciences Citation Index might find value in our work. After reading ISI’s guidelines (In six short paragraphs, we get the following friendly reminder four times: “A journal that is rejected for any reason (including timeliness) cannot be reevaluated for 2 years… Please do not resubmit a journal for evaluation if it has been rejected within the last 2 years. A reevaluation cannot be initiated until 2 years after the date of the rejection… If the journal is publishing on time and has not been rejected within the last 2 years, the evaluation will be initiated with the receipt of the first issue.”) and receiving the advice from a friend at Thomson to “make sure you use old fashioned snail mail in addition to submitting using the online form,” we decided to hold off for a bit.

- Library Literature (subscription required). We submitted our request to be included in Library Literature on December 9, 2008 and the next day we got a very nice request for more information from a contact with Library Literature’s publisher, H.W. Wilson. We responded immediately, and wrote back again on August 24, 2009 to let our contact know that our work would soon be appearing in one of its competitors’ databases, but we have not heard back from them since we received their initial response.

- LISA: Library and Information Science Abstracts (subscription required). We initially submitted our request for inclusion on December 9, 2008. At the time, a person’s name was listed and we emailed our request directly to her, but never received a response. ProQuest has since modified its process, so we resubmitted our request on November 22, 2009.

- LISTA (Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts) (free version available at libraryresearch.com). We wrote to EBSCO’s Director of Content Licensing on December 9, 2008, got a confirmation on December 10, 2008, and have nothing but good things to say about Paige Larkin, the EBSCO Publishing representative who has shepherded us through the process. She knows her stuff, she’s patient and responsive, and she’s done a wonderful job of addressing our concerns.

- Ulrich’s (subscription required). We emailed the Microsoft Word version of the submission form found on the Ulrich’s website to them on December 9, 2008 and were informed less than a week later that we had been added to their database.

- WorldCat (subscription version available). We asked a few catalogers at OCLC libraries to include us in their catalogs, but no one has ever stepped forward to receive credit for having cataloged us, and the citation itself doesn’t indicate which library chose to include us in its collection. Whoever you are, thank you for giving us a presence in WorldCat.

We also submitted our work to several other resources that aren’t specifically dedicated to scholarly research, including search engines Google, Yahoo!, MSN (now Bing), and Ask (all via the Google XML Sitemaps WordPress plugin, as well as Alexa and Technorati; DMOZ and the Yahoo! Directory; library-centric search engines LibWorm and LISZen, and librarian-created indexes Librarians’ Internet Index, Internet Public Library, and LISWiki; and we requested an article at Wikipedia. There’s no reason not to submit your work to these resources. Depending on your goals, it may make sense to pursue them even more actively than we did.

Be Fearless

The First Missile: The Cave Man of prehistoric times unconsciously invented arms and ammunition

It’s time-consuming to submit forms, edit wikis, or send email messages to people you’ve never met or can’t identify. It’s a lot more challenging, at least if you fear rejection, to send a personal message to people you’ve met professionally asking them to read your publication, review a draft of an article before it’s published, or submit a guest article. Of all the tasks I’ve taken on as part of In the Library, that’s probably my least favorite, but we all do it and it’s worked: getting other people involved has made our writing better and helped us develop an audience.

It’s tempting to start naming names and giving thanks to the people who have helped us, but that would likely come off as showing a lack of humility and may also encourage even more unsolicited email than these folks deal with already. Still, it would be almost deceitful not to mention the two writers whose links to our work put us on the map.

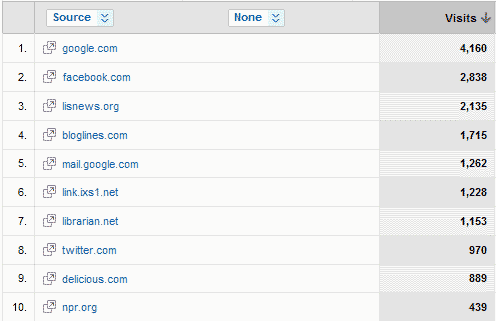

I wrote to LISNews’s Blake Carver the day before we went live. His response, “Hurray, just what the world needed, a new blog ;-) I’ll take a look tomorrow.” He did, and he linked to us, and that resulted in the lion’s share of our incoming traffic the first couple of weeks (an effect not limited just to new blogs; the well established Pegasus Librarian recently experienced a similar spike in traffic after a link from LISNews). Three months later, Blake included us in his list of “10 Library Blogs to Read in 2009,” which resulted in our second highest traffic and subscription increase ever. So far, more people reach us from LISNews than from any other authored website.

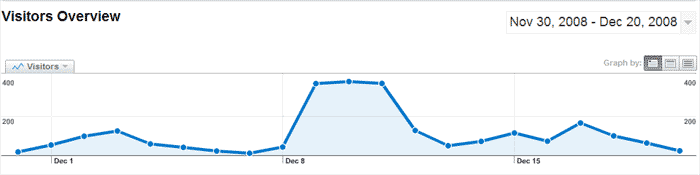

Our biggest leap happened the first time Jessamyn West gave us a write up on her blog, librarian.net, on December 9, 2008. We got another big subscription increase when she linked to Ross Singer’s guest post back in August.

Detail from our Google Analytics traffic analysis

Detail from Google Analytics: Traffic spiked the first time Jessamyn West linked to us

Experiment

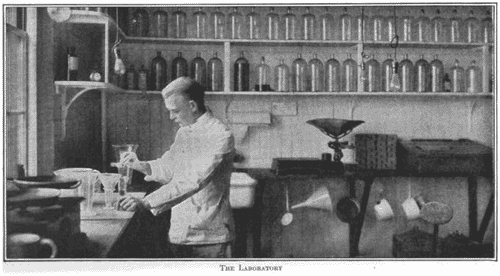

The Laboratory

We haven’t yet found a substitute for spending twenty-five or more hours writing and editing what some of us still think of as a blog post, but we recognize that’s only half the assignment: we need to keep looking for more ways to ensure that posts reach people. We’ve had some success with Twitter and Facebook, and considerably less success with Lead Pipe News, our attempt to create a Proggit/Hacker News/Stack Overflow for the library community.

We’ve also experimented with deadlines. We thought it made sense to publish weekly, but found that our writing was suffering, we were struggling to manage our time, and many of our readers couldn’t keep up with our output—our articles regularly exceed 5,000 words, plus our average post generates fourteen comments. So we scaled back to every other week and things seem to be better for all concerned.

This is one of the ways we differ from most blogs: as a rule, bloggers don’t seem to publish at specific intervals, while traditional print publications (or publications produced by publishers who are grounded in print-based models), generally distribute their work on a weekly, monthly, or quarterly schedule. I’m not sure that either model is better, but publishing every other Wednesday works well for us. Publishing online allows us to edit up to the last minute when we need to, either because our personal schedule necessitates it or information we’re discussing in the article is changing, and our regular publication schedule enables us to plan our own articles and line up guest authors several months in advance.

In addition to deadlines, we’ve experimented with our internal communication. At first, we started with a wiki, a private Google Group, and a series of chats on Meebo: the Google Group has been our mainstay, while the chats and wiki, though initially useful, proved less important once we got up and running. What we haven’t needed to do is meet face-to-face or via phone. Scheduling meetings is hard because, for the most part, we don’t live anywhere near each other or even share a time zone: Emily’s in Oregon, Kim’s in Idaho, Ellie’s in Texas, Hilary’s in North Carolina, Derik’s in Pennsylvania, and I’m in New Jersey. We’ve also grown to rely on Google Docs, both as an archive and as a way to collaborate asynchronously.

Virtual participation is a huge and somewhat divisive topic in the field, and I often find myself wanting to argue both sides. It can be helpful to get together in person—In the Library started, in part, because many of us attended the same meeting—but, in our experience, almost all of our work gets done virtually. Granted, we’re a small and non-hierarchical group with a fairly simple focus, we’re making our own rules, and we’re beholden only to our readers, reviewers, and each other. But it isn’t because of technophilia or any other ideology that we’ve arrived at our working style. We’re simply trying to do something people value, devoting as much of ourselves to this work as we can without throwing the rest of our lives out of balance. I don’t know exactly what conclusions others will draw from this, but my hope is that I’ll be able to bring what I’ve learned from In the Library to the other committees on which I serve. It‘s rewarding to work so happily and productively on something as successful as In the Library. I’d like to share that experience with others.

All images except for Derik Badman’s drawing of the In the Library with the Lead Pipe team and the screen captures of our statistics are from The Standard reference work: for the home, school and library, Volume 8, edited by Harold Melvin Stanford and published in 1921 by the Standard Education Society. An original of this work, part of the collection at Columbia University, was digitized on June 9, 2009. I downloaded these images from Google Scholar.

Thanks to Derik Badman, Blake Carver, Ellie Collier, Hilary Davis, and Jodi Schneider for commenting on a working draft of this article, and to Hilary Davis, Emily Ford, and Kim Leeder for helping me with its final version.

Brett – congrats to you and the team; In the Library is terrific. It’s one of the finer examples (from any industry) of the value of ‘new media’ — and has my vote for best library blog.

Thanks for sharing the ‘behind the scenes’ processes with us in this article. With so much written about the technical aspects of blogging, it’s really nice to gain insight into the range of other things involved in delivering such high quality work.

For me, you folks are the future of librarianship and a real inspiration. Best, Jean

Congratulations! The success you’ve achieved is well-deserved!

Lead Pipe is one of the few library blogs I make time to read these days, because it’s consistently excellent. Congratulations on your success, and thanks for the detailed explication of your group process.

Leigh Anne

Congratulations on reaching your first anniversary! Your articles are consistently thought-provoking, and as a newer librarian I learn something every time I visit. I especially appreciate your thorough documentation of the processes you’ve developed to collaboratively write, host and index your blog. Here’s hoping it inspires more energetic librarians to give it a try!

Kia ora koutou

I can’t even remember how I came across your site today, as I was working on some web-design, doing precisely what you talk about here – building a site from the ground up and not using blog software.

I have heard of In the library before, referenced on at least a handful of library blogs, twitter and LIS wiki’s and such. I agree totally that it is really refreshing to read a “post” on the non-technical aspects of writing and the processes you go through.

And also, I had a conversation with a customer at work (the library) yesterday about how to get into the publishing industry and editing. Timely. Very timely read.

Thank you

and CONGRATULATIONS!!! yay one year old!

Pingback : pligg.com