We’re Gonna Geek This Mother Out

“what to do with the waterfront” photo by Flickr user mulmatsherm (CC BY-SA 2.0)

By Ross Singer

I am not much of a book reader. I have a home computer. It has a working internet connection. Any interest I have in genealogy or local history could probably be exceeded serendipitously by talking to family or neighbors and by wandering around the city. As a family, we do not watch many movies. I cannot seem to pay attention to audiobooks. Our taxes are complicated enough that I use software to figure them out.

What I am saying is that I am not the target market of public libraries. Despite that, I am completely intrigued by them.

I worked for many years as a technologist in academic libraries. They were all large research institutions with big collections, budgets and staff. I was also not the target market for them either (at least not after I graduated), but I understood the principal demographics of their constituencies and their expectation of the library. I witnessed the shift in the academic library from book depository to IT shop (whether or not all academic librarians agree on this assessment). When the university library stopped being “the place where the books are” it began to lose some of its identity and many began trying to create “social spaces” within the library (presentation rooms, coffee shops, information commons, etc.). The primary purpose of these endeavors, however, seemed to be mainly to help market the library as the information hub of the institution. Since the information is available mainly via technology, and the technology makes the information fungible, it became necessary to reinforce the library’s importance to the community.

If this seems complicated, well, that is because it is. The future of the academic library is in little jeopardy, really, because its role and utility within the larger organization is pretty well defined and not easily replicated by some other group or service.

This is not to say (by any stretch of the imagination) that academic libraries are satisfactorily meeting the needs of their “customers”. Not by a long shot. However, if the academic library is increasingly becoming a technology organization then many of the academic library’s problems are technological problems, theoretically with technological solutions. The majority of these problems are at the intersection of “the way we have always done things” and “where do we go from here”. That is, these are technology problems that are enveloped in a sticky skein of sociopolitical issues. If the interminable committee meetings were ever to wear down that outer skin, it might just be possible to make some real progress. The library technologist’s hope springs eternal.

The public library, on the other hand, appears to be roughly the inverse. It is a primarily social service that has clumsily tacked technology designed for academic libraries to the top. Any argument for the merits of library applications pretty much breaks down when applied to the public library. The audience is different and their needs are different. While, without a doubt, enabling research is within the scope of the public library, in reality the vast majority of transactions there are far more modest. The public that the library serves, largely underwhelmed by our complicated bibliographic search tools, instead uses Amazon.com, a technology company that has quite cleverly tapped into social activities (lists, “people who bought x also bought y,” etc.) to pitch their products. Most importantly, the packaging is slick and effortless.

It is a shame—especially considering how interesting, fun, and rewarding the projects would be —how little public libraries seem to be able to execute their technology. Not that technology is ignored, indeed my local library employs a vast array of applications to try to aid its users. But this comes across as a hodge-podge: many different interfaces, none of them terribly satisfying and not in sync with each other. This is not exclusive to my library, of course, nor is it uncommon in an academic library setting. It would also be fairly easily remedied by some technical expertise, cooperation, and a little bit of vision.

Whereas the academic library is likely not in jeopardy, the public library is subject to far more fickle decision makers. If the primary benefactors of the service, middle class tax payers, see no benefits resulting from the library’s existence, it may find itself subject to political pressure. This is a population that, on the whole, is pretty wowed by style and convenience which tend not to be libraries’ strong suit.

Know Your Audience

My wife, Selena, is a steadfast supporter of the public library. She had an awakening about five years ago after shelling out tons of money to Amazon for books she read only once.

“Oh my God, they’ve got all these books. For free!”

At this point, we had been married for about four years and I had been working in a library for about ten. It is not like I hadn’t brought up the possibility of the public library before, but I had no defense for her complaints about the catalog’s interface (SirsiDynix’s iBistro). It took her requiring her high school students to get a library card to see the merits of the library and ever since she has been a devoted advocate.

That does not mean that she still doesn’t have her complaints. They are legitimate gripes and, thankfully, almost completely technical. Her issues are:

- There is no simple way for her to find the intersection of discovering new things that might be interesting to her and what the library has.

- The library interfaces are crude, unforgiving and provide little that is useful for the casual reader.

- Two-plus month waits for the most popular and current titles in the collection is counterproductive and fosters the notion that libraries are irrelevant or out of touch.

The third point is not exactly technical, I realize, but it has an effect on the library as a whole. This will not stop me from offering a technical suggestion that might help.

Tell Me What I Want

There are several opportunities in the library for serendipitous discovery: the children’s book room, the returned book cart, the new books shelf, maybe a staff picks list. It has not, historically, been the forte of the library catalog. One of Amazon’s many strengths lies in its recommendations and groupings. Simply by being me and doing what I do, Amazon finds and presents me with things I might be interested in based on how other people with profiles like me shop. While the recommendations are generally hit and miss, it made me aware of many things (especially music) that I would have had no way of discovering before.

There are various reasons that the library is reluctant to start creating profile based services for its borrowers: USA PATRIOT act style privacy concerns, population sizes that are too small to produce meaningful recommendations, etc. U.S. libraries should pay close attention to the UK’s MOSAIC project, however, a JISC-funded initiative to harvest and mine circulation data with the intention of providing recommendations based on borrower usage. Assuming concerns surrounding the differences in privacy rights can be met, this could really begin to pave the way forward for such services.

In the meantime, there are tangible ways to provide less targeted, although still meaningful, recommendations: best seller, award, and book club lists. Best sellers’ lists are, of course, a very rough metric of what is currently popular across America and, in the case of some lists, targeted at particular demographics (the New York Times, Essence Magazine, Evangelical Christian Publisher Association, Powell’s Bookstore, Independent Mystery Booksellers Association, etc.). While best sellers lists give no context of the actual content (outside, possibly of fiction or non-fiction) and certainly are no barometer to the quality of the work, they do at least provide a list of books that are currently popular, which might be all the discovery some users need, especially the specialty lists.

When I checked my local public library for access to their collection based on best sellers lists, I was rather surprised to find that they did not have any. This seemed so simple and such an easy win for them, that I thought I would mock something up so they could use it. The New York Times has opened their best sellers lists and book and movie reviews through their API service making it very simple to create a set of interfaces based on their best sellers to the library catalog. Unfortunately, this proved to be harder than I originally had hoped because the library catalog has no machine readable interface. There is no easy way to provide mashups to my library. This is not terribly surprising; the same was true for Atlanta-Fulton County Public Library’s catalog. This is a terrible shame. If the library is unable to provide the resources to create interesting and vibrant technological services, they really should do everything in their power to facilitate these services being created by members of their community. This is exactly how Ann Arbor District Library cultivated its “Super Patron”, Ed Vielmetti. Ironically, the AADL already had a strong technological base and probably needed to depend less on their constituents than other libraries. I suppose this stands to reason, though, what with the rich getting richer and whatnot.

Quasi-tangential Rant

The issue of completely closed systems resonates with me especially hard. For the last two years, I have been working on a project to build a specification to provide access to library data, via the Atom Publishing Protocol, called Jangle. I was my employer’s representative to work on the Digital Library Federation’s Integrated Library System and Discovery Interface API. This year, my work has primarily been split between trying to herd Jangle along and trying to find opportunities to expose library data and services as Linked Data. I also wrote a book chapter on possible ways to make your library data more accessible for mashing up. Sadly, all of this is an exercise in futility if libraries have no machine readable accessible means to provide their data. This lack of openness is a major setback to libraries and the potential services they can offer their users.

The Worst of the Best Sellers

While I was trying to figure out a new plan of attack for implementing something like this, I did find that best sellers lists are not uncommon in public libraries; a cursory scan found them at Atlanta-Fulton Public Library, Knox County (TN) Public Library and the Nashville Public Library among several others. The AFPL and Knox County PL both had them integrated directly into their OPACs. Both use SirsiDynix powered OPACs: the AFPL uses iBistro and Knox County uses Rooms. Nashville Public Library uses BookSite.com, a third-party service that compiles lists and tries to emulate the look and feel of the original library website.

They all suck.

The problem with BookSite.com is that it, apparently, has no way to check the host library to see if the selection is even in the collection, much less if it is available or when it will be. This requires the user to click on the link, initiate a catalog session, see if the item exists, check the availability, click the back button, find the next item of interest, click on the link, enter the catalog, etc. While this may not seem terrible, every time they follow a link for an item that does not exist or is not available diminishes their confidence that they will ever find something available. Let us not forget, also, that our OPACs tend to be horribly slow at initiating or reallocating sessions. All of this just adds to a frustrating user experience. This is another example of where a lack of APIs hamstrings third-party developers: despite the intentions of the library to provide a better experience by purchasing subscriptions to products like BookSite, the end result is still awkward.

One would then think that incorporating these lists directly into the OPAC would be an improvement. Unfortunately, this is not really the case. While item availability is shown (assuming the item is even held), the display is just an ugly, OPAC title list view. Understandably, practically any title that appears on a best sellers list is more than likely going to be checked out (and will probably have a wait). From a user’s perspective, though, this offers very little as a “discovery interface.”

“Gee, thanks for showing me a list of books that I cannot get access to for at least a month.” Photo by Flickr user inkcow (CC BY 2.0)

Quite a few of the the entries were fairly misleading as well. They provided hope for the user that the title might actually be available, but required going to the full title screen (similar to BookSite.com), only to see that all of the copies are, in fact, unavailable; they just have some status set that the OPAC cannot recognize as “available” or “unavailable.”

What is unacceptable here is that the poor user is presented with a list of 15 dead ends. If the library is unable to provide any of these particular titles, what can it offer the borrower that might be related or relevant? Each of these books represents a possible avenue of interest into the collection. They also define a particular point of interest in the collective national consciousness that can be utilized to present other works held by the library that may not be new, but could be just as much of interest to the user. The “traditional” library avenues of providing similarity tend to be fairly weak substitutes when it comes to this. Dewey Decimal Classification (common to the majority of public libraries), which provides the “shelf browse,” is completely ineffective in the case of fiction works for anything other than finding other titles by the same author or another writer with the same last name. Browsing on subject headings is also a rather blunt tool. “”, “Female friendship Fiction.”, “African American women Fiction.”. None of these, individually, captures the essence of why a particular book is on a particular best sellers list. The MARC 65x field is unable to capture timbre. And this is huge area where the public library is failing the public.

An Obvious Market Opportunity

There are products and projects that begin to address this disparity between what the casual user wants and expects and how the library catalog has evolved (or not) for the web. BiblioCommons’ business model is to provide this social context layer over the collection by facilitating and aggregating circulation data, reviews, lists, and other means to allow library users to directly influence the relationships between works. SOPAC could be considered an open source alternative to BiblioCommons; it is a suite of components featuring a public interface built atop the popular FLOSS content management system Drupal. One of the pieces, Insurge, is intended to provide a means to share this social data between the various implementations: reviews, ratings, and recommendations. The design of Insurge theoretically allows it to work independently of SOPAC, the Drupal module, although, in practice, this has yet to happen. Both of these are complete OPAC replacements, relegating the integrated library management system to its rightful place as an inventory control system.

At the other end of the spectrum is LibraryThing for Libraries, which takes the incredibly pragmatic approach of integrating into the existing vendor-supplied OPAC interface. Like the other two, it leverages the much broader LibraryThing community to help enhance the local collection. Of the three currently available options, it, by far, provides the richest and most comprehensive social enrichment because the community already exists. The others have to build this community and the content from scratch. One has to wonder, really, how Syndetics has sold a single subscription since LTfL was released: LibraryThing gives everything a Syndetics subscription could, plus gives the user relevant alternatives from their own library’s collection.

That being said, LTfL also shares the same limitation as Syndetics (or any other “shoehorned in the OPAC” enrichment package): the OPAC is still there. This content, these tags, the ratings: none of these are available to the searcher until she has already found something. Queries do not include this community supplied content, there is no spellcheck, results cannot be sorted by rating. If public libraries are to stay relevant, these interfaces have to be dropped. The future of the ILMS itself is a different matter entirely, though its usefulness as an inventory control system is out of scope here. This is just about the OPAC.

It’s the relationships, stupid

I strongly believe that the future of the public library collection interface has to be tied into some kind of content management system. I am unable to find any hard statistics to back this up, but I do not think it is much of a stretch of the imagination to say that a vast amount of library circulation is casual, popular reading. Just walk into any branch and browse the collection; the overwhelming majority is not research material. While certainly there are lots of archival, local history, reference, and research items at any public library, can any one of them, honestly, say that these types of activity make up the majority of what cardholders want, need, or expect to do there? Why, then, are the interfaces optimized to perform these tasks, arguably, at the expense of the majority? Of course, sophisticated information retrieval still needs to be supported—the line between “hobby” and “research” can be blurry—but perhaps it does not need to be the primary function of the public interface. The social nature of the library as place and collection need to be merged.

The concept of CMS as OPAC is not new or original (or exclusively useful to public libraries): as previously mentioned, SOPAC is a Drupal module, as is the Mellon Foundation-funded eXtensibleCatalog (XC) project. Scriblio is a plugin for the WordPress blogging platform. Several years ago, I was working on a project to build a catalog using the Daisy CMS as a back end. Even SirsiDynix’s Rooms was an attempt to merge the content and collection, albeit with the aesthetic of a traditional web OPAC, the speed of federated search engine and the general user experience of a root canal. At a certain point, a library collection grows to a size that it cannot feasibly be dynamic and fresh using only the catalogers as the sole editors of the content. There is a growing need for “marginalia,” independent of the MARC record, to tie the individual items within the library to each other, to events, to groups, to anything. The separation between the “catalog” and the general information about the library makes no sense.

In the Absence of Suggestion, There is Always Search…

Besides the integration of general content, collection, and public contribution, the single most important improvement needed for the public interface is search. It is amazing and somewhat appalling how, despite our claims that our systems are designed as being highly advanced information retrieval tools, they fail utterly at retrieving information. My local public library recently deployed the federated search product WebFeat, undoubtedly in a well intentioned attempt to help their users navigate the various silos of information that inconveniently require searching individually: the catalog, the audiobooks, the photograph collection, and the various databases they subscribe to. It is also, by the gentlest assessment possible, a complete train wreck of a user experience. Besides being slower than the stock catalog interface, it does a terrible job at searching. It is understandable that the library would want to highlight and improve access to their database collection (as well as have a unified search interface for their “general collection”), but it does not seem likely that a borrower looking for something by Nora Roberts to take with them to the beach cares much about results from InfoTrac OneFile. Requiring said borrower to enter their library card number before they can search just lessens the experience even more.

Another requirement the library places on the searcher, that they must be an excellent or informed speller, is also unfortunate. As I try out these interfaces, there are two searches I try so I can see how effective they are in aiding the hapless searcher. The searches are “Olive Kitteredge” and “Jody Picoult.” It is depressing how unhelpful our search interfaces are.

For “Olive Kitteredge,” an understandable misspelling of Olive Kitteridge, the Pulitzer Prize winning best selling book, I got:

- Knox County’s SirsiDynix Rooms gave me a did you mean “Olive skittered”. Olive skittered also produced zero results.

- Atlanta-Fulton County’s SirsiDynix iBistro gave me no recommendations, just zero hits and placed me in a browse index. “Olive Kitteridge” did not appear within ten pages forward or back.

- Nashville Public Library’s III Millennium catalog gave no recommendation, just zero hits and returned me to the search form.

- Darien Public Library’s SOPAC gave me no recommendations, no results.

- Chattanooga-Hamilton County’s WebFeat search gave the recommendation “olive kittredge” and no results. “Olive kittredge” also produced zero results.

- Seattle Public Library’s Horizon OPAC displayed “Did you mean: olive kitteridge?” Success, at last. This is not a stock Horizon feature, howeve. Other Horizon libraries just gave zero results, zero recommendations.

- Oakville Public Library’s BiblioCommons presented: “Did you mean olive kitteridge (1 result)?”. Another satisfied customer.

- Collingswood Public Library’s Scriblio catalog not only tried to autosuggest the proper spelling as I was typing in the search box, despite submitting my search with the misspelled title, Olive Kitteridge was still the fourth result.

Seattle Public Library getting it right. Photo by Flickr user inkcow c/o

Scriblio’s autosuggest to the rescue. Photo by Flickr user inkcow c/o

“Jody Picoult” seems a perfectly reasonable misspelling of the multiple best selling novelist and author of My Sister’s Keeper, which was recently adapted to film. In the same order:

- Knox County’s Rooms gave no spelling recommendations and placed me in a browse search. “Jodi Picoult” did not appear anywhere forwards or backward.

- AFPL’s iBistro timed out my session, gave me no results and placed me a browse index. “Jodi Picoult” did not appear forwards or back.

- Nashville PL’s catalog: “No entries found”. Return to search form.

- SOPAC: no results, no recommendation.

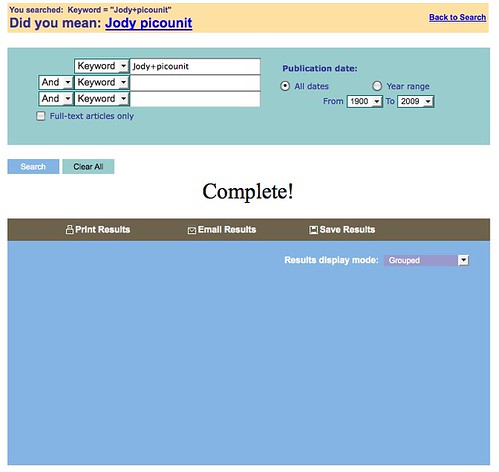

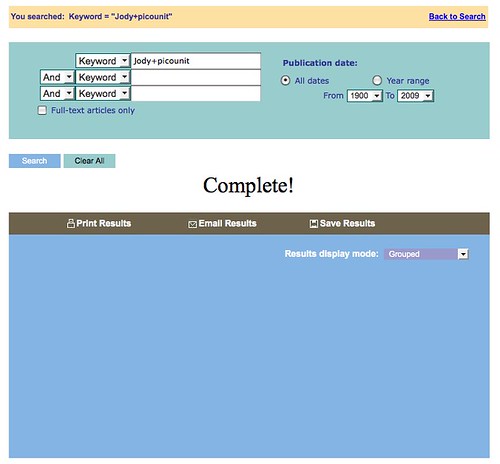

- WebFeat: “Did you mean: Jody picounit”. Jody picounit, unsurprisingly, returned zero results. WebFeat did not give a recommendation for alternatives to “Jody picounit”.

- Seattle Public Library, despite passing the Olive Kitteridge test, returned one result: Super searcher, author, scribe: successful authors share their Internet research secrets by Loraine Page. A content note includes the string “Jody Picoult” (presumably a misspelling of the author in the MARC record?). No suggestions or recommendations are given.

- BiblioCommons, again, aced this: “Did you mean jodi picoult (29 results)?”

- Collingswood’s Scriblio did not provide a correction in the autosuggest, but a Jodi Picoult book appeared as the second result, averting user frustration (and also providing a teachable moment on the author’s name).

Complete! Don’t you feel completely satisfied? Photo by Flickr user inkcow c/o

My library still has no Jody Picounit. Photo by Flicker user inkcow c/o

These are not edge cases. These are searches for current best sellers and a Pulitzer Prize winner and both of them are only off by one letter. Of the sixteen searches, eleven of them ended in failure. While not comprehensive, these were eight libraries chosen mostly at random. For all of the current fixation in faceted and graphical search results (and to be fair, Queens Borough Public Library’s AquaBrowser implementation passed the Picoult test and provided “kitteridge” in its similarity graph), none of these bells and whistles matter one whit if the search interface cannot even help the user past the search screen. Amazon not only presented the correct “did you mean” suggestions, it also provided relevant search results with these bad searches.

Photo by Flickr user inkcow c/o

Ebb, Meet Flow

Of course, correcting a search for “Jennifer Wiener” to Jennifer Weiner is irrelevant if the book the borrower is interested in will not be available for 89 days, as the Knox County Public Library was displaying last week for Best Friends Forever (as of this writing, the New York Times #1 Best Seller for Hardcover Fiction). That is nearly three months. Forget summer reading, you will be lucky to get this book before the winter solstice. While I am normally extremely supportive of large, cooperative borrowing consortiums, such as Georgia’s PINES, the advantages of such a system, regardless of the size and scale, still completely break down when it comes to such enormous spikes of popularity. It does not matter how many copies are in the system if everywhere from metropolises to backwaters has a run on the same title. This is not exclusive to best sellers, of course, consider titles on school curricula or summer reading lists. Backlogs are bad for credibility.

Popularity, however, is fleeting. It is unreasonable for an underfunded library system to exhaust its limited collection development budget purchasing dozens of copies of the new hot thing which tomorrow may not circulate again ever (consider James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces). For cases such as this, rather than borrowing from other libraries that have nothing to give, it makes more sense to borrow from the public. Many of these most popular titles are best sellers, after all, and “best seller” by its very meaning implies that a lot of people own that book. Once read and passed around to your circle of friends, what do you do with this book? For these very popular, highly circulating titles, it makes sense to create a system that allows book owners in the community to donate their copy. Once a particular title passes some predefined threshold (two holds for every copy, as an arbitrary example), provide a link in the best sellers list to encourage people to give the library their copy. Links to this page would need to be present elsewhere, too: after all, the person that owns the book wouldn’t be looking for it on the library website since they already own it. Advertise on the library website. Have an announcement on the local NPR affiliate. Post the list of books the library wants to have donated near drop boxes.

The donor would be given a tax write off based on the value of their book on the open market. When the popularity spike diminishes, the library could either return the book to the original owner or, perhaps, register itself as an Amazon affiliate (as an example, I am not sure of the legalities or practicalities of this, nor is this an endorsement for Amazon.com) and sell the used copies with the proceeds going back to the library like any friends of the library book sale. The tax write off (as well as satisfaction of performing a public good) would probably be more desirable to many potential donors than going through the process of selling the book themselves.

The Medium is the Message

What all of this points to is that public libraries need to place as high of an importance on the technology that they do on the social and physical aspects of their organization. A lot of effort goes into speaker series, story time, game nights, and movie nights. A lot of planning. A lot of investment. If that investment is not given, nobody will come to them. The web presence is no different. If the web tools are an afterthought, a haphazard, sloppy collection of off-the-shelf tools that neither help the user achieve their goals nor captures their interest, the public will write the library off. Just as a speakers series is a combination public service and library marketing tool, the web site must be more so, as it is more public than any event.

At the same time, the library should not have to break the bank investing in the most cutting edge and expensive technology (or worse, break the bank with the run of the mill, dreadful applications currently pitched to them). Many of these issues could quite easily be addressed simply by hiring a competent and creative developer. By pooling these development resources, even more ambitious accomplishments can be achieved. Georgia PINES (despite OCLC’s marketing department’s claims) built the first truly “web scale” ILMS simply because they had a need and were willing to devote the resources towards building it. Joe Lucia, the University Librarian at Villanova made an intriguing and provocative statement on the NGC4LIB mailing list two years ago with this:

“What if, in the U.S., 50 ARL libraries, 20 large public libraries, 20 medium-sized academic libraries, and 20 Oberlin group libraries anted up one full-time technology position for collaborative open source development. That’s 110 developers working on library applications with robust, quickly-implemented current Web technology…. Instead of being technology followers, I venture to say that libraries might once again become leaders….”

He was speaking in this case of academic libraries (he mentions 20 public libraries, but I remain unconvinced that the average public library has all that much in common with its academic counterpart), but it is not too difficult imagine this in the context of public libraries. There are, after all, nearly three times as many public library systems in the United States as there are academic libraries. Surely, collectively, they could figure out how to fund such an endeavor to provide a truly powerful development team committed solely to the technology needs of public libraries.

If added to this was an infrastructure and environment that cultivated an opportunity to harvest the contributions of “super patrons” and “citizen developers,” as well as graphic designers, usability and accessibility experts, entire services could be provided by the constituency just as BiblioCommons, LibraryThing, or SOPAC solicits content. One of the many distractions I had while writing this article came from a desire that I had to not just complain about my public library, but actually build some alternatives that could be contributed back to them. However, as I mentioned previously, there is no machine readable access to their collection for me to build upon. In order to write something interesting and, hopefully, useful, I first had to write a crawler to harvest their catalog. I have yet to gain the nerve to actually run it; there is no robots.txt file, but it still seems rude and underhanded. It is also ridiculous that I have to resort to such tactics just to sketch out some proofs-of-concept.

If all three tiers of this ecosystem were to become a reality (cooperative development team, local developer resources, and a public contribution network), the library would be well-placed to remain relevant for many years in the community’s consciousness. It is difficult to see if the initiative or vision is available to establish such an environment, however. Significant improvement would be rather easy to accomplish. All it would take is a little imagination and some commitment.

Maybe I should just start my crawler and see what happens.

Thanks to: Brett Bonfield for not only convincing me to write this article, but also tirelessly reviewing it and for guiding this along even when I was getting flaky. Also thanks to Dan Chudnov for reviewing it and helping me find a better focus, even if he agreed with only about half of what I wrote. Lastly, I’d like to thank my wife, Selena, without whom I would have had no inspiration, ideas, or “research subjects.”

Great post, really enjoyed reading it and has given me lots of ideas.

But rubbish title!

Coming from a public library background, this article doesn’t bring anything new to the table. We are a multi-faceted community resource that is just as valued as any academic library. There are some communities that do not value their local public library, but those communities are in the minority. If you look at the track record of these communities, you would probably find that they make other poor decisions.

Many public libraries don’t have the resources to provide a copy to anyone who wants the latest best-seller. (If you read the latest Unshelved, they answer that question. “If we did that, all we would have is 10,000 copies of vampire novels and nothing else.”)

Many libraries use third party services since many cannot afford and don’t have the know-how to develop these things on their own.

Amazon is king of the bookselling world and they have defeated or subdued most of their competitors with their knowledge, algorithms, and now their weight. It’s old hat to make the comparison, you aren’t the first, but to put in it’s proper context you wouldn’t compare Amazon to libraries. We both have books, but we play different roles. (Also, the service is Bookletters not booksite.com. It’s a common mistake.)

The real problem isn’t the technology interface. The real problem is getting people into the library to learn, read and explore. People don’t drill down and explore the world around them, or even themselves. They are just satisfied with what is put before them without question. How do we change that?

Jeff, I think in some ways you are reinforcing my point. A powerful, dynamic and (most importantly) useful web presence has a secondary effect of being a powerful, dynamic and useful marketing tool.

You are right, people are not going to just go down to the library, therefore it is important to also engage them on their terms and convince them it’s worth their while to come in. What I am trying to say is that the quality of collections and services don’t matter if the audience has no idea that they exist. The onus is then on the public libraries to realize that the web services are as much a priority as the physical services and should be committed to accordingly.

Libraries, public as well as academic, are increasingly becoming technology organizations: academic libraries just seem to be quicker to acknowledge this.

Thanks for the great post! I’ve always hated our OPAC but could never adequately articulate why… It never does what I want!! But, in this article you have articulated for me why are catalogs are so bad. One example: I am working on genre lists and wanted, for my own personal use, to create a link in my word document so I could see the availability of the item with one click, but iBistro won’t let me do that. I just get an error message. But, there does seem to be hope because you pointed out at least two OPACs that were helpful.

My favorite thing in the article: Your succinct list of the three things our users want but don’t have!

Ross, thanks for the response.

This is what I think a catalog entry should look like:

http://books.google.com/books?id=u6CIHSfrSEQC

It’s true everyone else is going to get their book information from another source, then see if it is available at their local library. A library is almost never the front runner on informing someone for a new book. Others have more marketing power than we do. Our advantage is we offer the same book for free.

Better websites are needed, but it is only one tool. I also have to say that the article comes off as a little condescending to public libraries.

The unforgiving nature of spelling in current opacs is a true pain for librarians as well as for the public. I do believe that the software will evolve to allow for corrections but I fear the cost.

As to the lack of copies and long wait periods, Maine along with a number of other geographic units has established a statewide interlibrary borrowing program which regularly cuts the waiting period significantly for new titles. Unfortunately the delivery company quit so that system is on hiatus but it is expected to be up and running within the month.

Libraries are not yet at the ideal stage of being able to supplyu everybook to every reader but we have come a long way since the dreaded card catalog.

Boy do I wish we had the IT staff to develop an opac that would be user friendly in this way. As is, unfortunately, we don’t even have a full time staff member to work on the library’s website (this is for the CITY keep in mind), and budget cuts have eliminated any future hiring. I think it is somewhat unrealistic to assume that public libraries aren’t making the changes because we don’t want to, but these things cost money and we don’t even have the funds to hire an outside web designing company. Unfortunately as more people need libraries, money is being taken away from library service. Frankly, I’m just happy they haven’t shut down my branch.

Ross,

Thoughtful, full of your taking-things-to-task for what really is needed.. like spell-checking in Library Catalogs, how long have we needed that?

I have some hopes for the new WorldCat Local and Worldcat.org, but their recent cataloging policy (re-use) snafu makes me leery of their vision at the top.

Public libraries need help with technology, and the vendors in the community aren’t doing the job; maybe the OLE Project will save us :)…

Keep writing!

DrWeb

I’m a systems librarian (I speak geek, but don’t program) and I”m running into many of these issues with our OPAC.

I’d like to note in there though, that there is a machine readable interface for library catalogs, you can make queries over z39.5 on almost all library catalogs. The YAZ client is the most common foundation on which those machine interfaces are built.

Brett, our OPACs are a fairly universal struggle.

Z39.50 access is not a given, however. While it’s basically ubiquitous in the academic setting (since it’s a requirement for things like EndNote), Z39.50 servers appear far less often (I would wager that they are the exception rather than the rule).

Many vendors charge extra for the Z39.50 server and, as far as I can tell, CarlWeb (which is what my public library uses) has no option for a Z39.50 server at all. There are probably others that have them, but do not make the service active beyond their firewall.

So, in fact, many public libraries truly do not have a machine readable interface.

DrWeb, unfortunately, Worldcat Local (University of Washington’s implementation) also fares pretty badly on the spelling test. The OLE Project will definitely provide machine readable interfaces, but who knows when, nor how relevant they will be to public libraries. That being said, I wouldn’t be surprised to see some of their recommendations find their way into Evergreen.

JC, my intention here isn’t blame the victim: I completely understand the reality of the financial situation public libraries are placed in. There is a point, however, where this becomes a “death spiral”: the library, unable to implement anything on their own, continues to have its budget slashed because the perception of its value wanes. For these cases, it’s even more important to have machine readable access (even Z39.50 would be a start), so there is at least the possibility of soliciting new services from volunteers in the community.

Peggy, I’m interested that Maine is able to (mostly) keep up with the demand. Do you know the typical trends in how this is compensated? That is, do the rural libraries tend to subsidize the suburban and urban ones until the popularity wanes? PINES doesn’t seem to say when a particular title will be available (at least, not that I noticed), so I can’t really use them as a comparison.

I agree, though, that large (regional, statewide, etc.) interlibrary lending consortiums would solve a lot a problems (and if it solves this one, then I can see almost zero downside).

Trista, thank my wife for the list.

z39.50 is not a great way to get data: rather limiting, slow, and a pain to build queries with.

Just testing threaded commenting…

And even more threading.

Catalogers at one institution may use a consistent style in original cataloging, but across institutions: I doubt it. Yes, there are standards, but cataloging is as much art as science. No two librarians will catalog something the same way; no cataloger will accept the work of another; and (generally) no cataloger will accept her own work 6 months later. So while I love a lot of what you’re saying, and I understand many of the issues, I don’t know that this will ever be possible given the current technologies. Frankly, we’d need something like One Database to Rule Them All. Aside from that, there’s something that bookstores offer which I wish libraries would do (but if they do, I have not seen it): it’s called “hand-selling”. As in, having a staff member who knows the stock and the customers well enough to be able to put the two together, successfully, time after time. Independent book shops do it all the time. Libraries? I don’t know. Thanks for the thoughtful piece, Ross.

Pingback : HotStuff 2.0 » Blog Archive » Word of the Day: “depository”

Thanks so much for this thought provoking post. For me the most interesting thing is the quote from Joe Lucia and your extrapolation on that. This is exactly the kind of “crowdsourcing” that libraries of all types need, because we all know that we can’t do it on our own and haven’t we become experts at sharing knowledge and resources? Well, it would be absolutely brilliant and could arguably become necessary for us all to contribute to such a project in order to compete in a shrinking market.

this article inspired my totally awesome library catalog here.

sorry, didn’t close the quote, here

Karl, I, too, find the Joe Lucia quote intriguing and am a little disappointed that it has (so far) not really gotten any legs (although, to a degree, the OLE project is based — in a smaller scale with a smaller scope — on this sort of model). For many years, I have fantasized about starting a library analog to the Apache Foundation: cherry picking a dozen or so of the most talented developers in the library, building a few open source applications and helping incubate others (as well as contribute to them). I am probably not the ideal person to run such an organization: far too disorganized, far too impolitic, but a person can dream, right?

If said organization created the infrastructure to foster the sort of community supplied development that I described in the article, well — the sky’s the limit.

Can I work for you please?

Seriously, that’s exactly what’s needed. Convince Mellon to fund it, get Roy or someone to be the director, I’m on board in a heartbeat.

THe quote from Joe Lucia mirrors a comment of my own about the same time (no, really!) — which I’m sure says more about the Zeitgeist than any prescience on my part. Interestingly, a team of 110 developers would actually dwarf the development team in most (all?) of the current ILMS vendors — there’s a reason they are so slow to respond to enhancement requests.

The wonder to me is, that given the oft-mentioned cooperative leanings of librarians, they have, largely, not yet embraced open source development.

Excellent post, by the way.

One key point about Bibliocommons is that it includes a fully integrated My Account feature. It is not just a search tool, it is the complete user experience.

We are moving from iBistro to Bibliocommons in the next few weeks. Our customers will get:

– dramatically more relevant results (+spell checking)

– facets for narrowing results

– tagging, rating, reviewing, adding videos

– building lists, sharing lists

– fully integrated my account (which really facilitates the rating and reviewing of stuff you have out or have recently returned)

At this point BiblioCommons give the integrated experience of a vendor’s product (like iBistro).

Search results like endecca or aquabrowser

Well thought out web 2.0 interactivity

Shared user content from multiple libraries – the necessary critical mass to build activity that generates activity.

I am not aware of anything else in the market that brings all these pieces together.

Peter

Edmonton Public Library

Are you keeping Syndetics or other enhanced content when you go with Bibliocommons? Book covers and reviews are the best thing we’ve done with the catalogue for patrons IMHO. BC content seemed pretty thin last time I looked (yes, only Oakville PL is live though?)

Steve, many of us who think of ourselves as enlightened look at Lucia’s quote and think, “Wouldn’t it be great if every library director were like Joe Lucia? Wouldn’t it be great if they all got it?”

But maybe some of our assumptions are backward.

For one thing, while directors seem to keep paying for proprietary software, they keep hiring programmers who embrace open source and open standards, even on the job. So it’s certainly possible that directors, in general, are agnostic and pragmatic when it comes to software licensing, and, all things being equal, they may even favor open source.

It’s also possible that software companies are slow to respond to requests not because they aren’t big enough — not because they have fewer than Lucia’s 110 programmers — but because they’re too big (and bureaucratic). I tend to get really good customer service from new start ups, even though many of them have just one to three programmers. The key to getting good customer service and useful enhancements is making these requests to the right start ups with the right programmers.

And I think that’s where libraries may be failing. We might well be following the wrong model. We’re doing agile development in a pseudo-corporate environment and holding out hope for Lucia’s 110 programmers. Which very well could be exactly the wrong way to get out of the situation we’re in.

We should be looking at Paul Graham’s YCombinator (here’s a nice audio intro to YCombinator, with plenty of links to more) or the Google Summer of Code model — small, talented, inexpensive, lightly supervised, and unencumbered (by job or life responsibilities) programming teams who are encouraged to take risks. The keys to YCombinator and Summer of Code are evaluation, volume, and incentives.

We have the programmers available to evaluate applicants: code4lib folks have the knowledge and drive, and they excel at making well informed, democratic decisions.

Volume is a question of money, though funding perhaps 20-30 small teams per year would cost a lot less than hiring 110 full-time programmers.

The issue may be incentives, though being given an opportunity to create interesting software for libraries seems to be enough incentive for many outstanding programmers. The prestige of being part of a library-funded, competitive YCombinator/Summer of Code-like program may well be enough to attract talented, hard-working programming teams from around the world who want an opportunity to prove themselves as coders, and help libraries in the process.

Excellent essay. Haven’t gotten all the way through it yet myself, but on this topic:

“# There is no simple way for her to find the intersection of discovering new things that might be interesting to her and what the library has.”

I have a vision of combining an (enhanced) version of the LibX toolbar, with my Umlaut link resolver software (which in turn uses both your local library systems and services like WorldCat), to _add_ information about availability in your specific library to Amazon (and other pages). You could definitely add a link to get such information (oh, I’ve found a book I want, does my library have it? Or if not can I ILL it from my library?) to an Amazon page. You could probably add the info directly on the page too.

This is totally do-able, the building blocks are there, I think I could do it in a month or less of work (that’s a month or less of work on top of all my other usual software custodial duties!).

But even once done, the software you’d have to maintain/deploy locally might be too much for a public library, sadly.

These terrible OPACs are the single biggest problem in public libraries today. Seriously. Nearly every project I’ve worked on has been negatively impacted by the limitations of Sirsi’s product. Nearly every complaint we get about our website is really a complaint about a Sirsi shortcoming that we have no control over.

You see our users frequently “confuse” the web catalog and the website proper. That’s because almost everyone visits us online in order to search for materials. This should tell us that a a good catalog is much more important than a great web page. So many libraries roll out these shiny new websites, but as soon as you search for a book, you’re dumped into some god-awful interface.

Thanks for outlining the problem so well. I see a lot of challenges ahead in implementing a solution, notably technological expertise among staff. But developments like Biblio, SOPAC and Koha are encouraging as they achieve more traction.

Our creative and highly competent systems librarian took a stab at fixing the flaws in the SPL catalog… take a look now with the misspelled search: jody picoult. More “did you mean options”. This is true for any search that yields one result or only one page or less of results.

Thanks!

Pingback : An article of interest « The Cataloguing Librarian

Excellent suggestions.

The criticism leveled at Nashville Public Library’s booksite lists is accurate. These lists are compiled independent of the library’s holdings, so some items in the lists cannot be located in the library’s catalog because they are unowned. This is a big problem that should be corrected with a better technical solution that removes these titles from the list to begin with.

However, the majority of the books in these lists are connected directly to the items available in the library catalog with the “Find In the Library” link. So, in most cases this service is helpful.

Still, it is not ideal, and does not approach the better bibliographic advisory services offered at Amazon.com.