Libraries: The Next Hundred Years

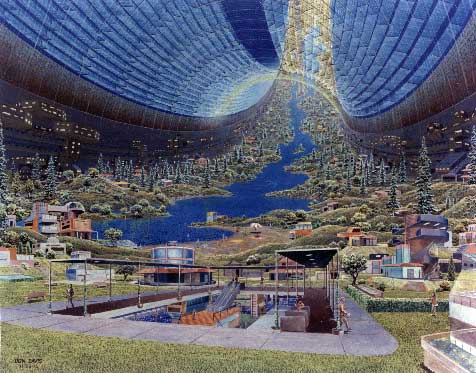

Space Colony Art from the 1970s: Toroidal Colonies, Interior View (via NASA)

Usually when we discuss the future of libraries, we’re talking about a year or two in the future, maybe up to ten. We look at forward-thinking libraries like NC State, or Darien Public Library in Connecticut, or maybe the initiative Nate Hill is helping to lead in Chattanooga. But for this article, I’m interested in a much, much longer span of time: the next hundred years.

One hundred years is not all that long of a span: one lifetime, or maybe two or three. When we try to think forward into the future, one hundred years can seem incomprehensible, a temporal illusion that makes it seem almost infinitely remote. But when we look backward, it can amaze us how quickly the time has passed. For that reason, I want to briefly cover the last hundred years in order to explore how much librarians in 1912 knew about us, and how they shaped where we are today.

That exploration starts with Dr. Sarah K. Vann. She died just a few months ago, at age 96, and I’m still shaken by her loss. I became a fan of her work soon after I began studying library history. As Dr. Vann wrote in her dissertation, which she completed at the Graduate Library School at Chicago in 1958, the first modern era of library science education started with Melvil Dewey and lasted until the publication, in 1923, of a report that Charles Williamson prepared for the Carnegie Corporation.

Dr. Vann is a direct link to Charles Williamson. One of her books was a study of the Williamson Reports, which ushered in the second modern era of library science, an era I believe we’re still in today. The Williamson Reports, which were underwritten by the Carnegie Corporation, helped lead to the accreditation process for library schools, and it also led directly to the creation and proliferation of modern library education, most notably at the University of Chicago (whose library school was underwritten by the Carnegie Corporation). The Graduate Library School at Chicago awarded the first Ph.D. in library science in 1930 and “(f)or the next twenty years up through 1950 Chicago was the sole awarder of the doctorate—at least one and as many as six per year during this period for a total of sixty-five degrees” (Bobinski, 1986, p. 699; see also, Richardson, 1982).

While Dr. Vann was working on her dissertation, she met Charles Williamson, and he wrote her two letters. In those letters, we learn that one hundred years ago, in 1912, Williamson had just been hired by the New York Public Library, which was working on a new grant from the Carnegie Corporation to set up its own library school. He helped provide assignments for the students and sometimes served as a lecturer. As he wrote to Dr. Vann, “I am afraid I always had a rather dim view of the nature and quality of the instruction in that school, including especially my own little part in it. Later I found that the School at the New York Public Library had the reputation of being one of the best in the country” (Vann, 1971, pp. 191-192).

It’s clear from this passage that Williamson, in 1912, was beginning to form a vision for library education. That vision turned into the education library schools are still providing today. In 1918, Carnegie hired him to help with its Americanization Study. In 1919, it hired him to study library education. In 1921, he turned in that report. In 1923, a revised version of that report was published. A few years later, based in large part on Williamson’s work, the Carnegie Corporation funded the Graduate Library School at Chicago.

Dr. Vann’s scholarship links us to Williamson’s studies. Many of Dr. Vann’s students are working in libraries today, and are also educating library students. So that’s roughly one hundred years in one or two or three lifetimes.

But just because we can traverse one hundred years so quickly, is it practical to think about? I think so. In fact, I think it’s not only practical but necessary.

Why We Should Look 100 Years into the Future (part 1): “The Hundred-Year Library”

The first reason I think it’s necessary is based on an argument made by Paul Graham, a programmer, essayist, and probably the most influential venture capitalist in the world. One of his best essays is called, “The Hundred-Year Language.” The idea is that we’ll still have computer programming languages in a hundred years, and programs written in these languages will provide the necessary code for all the cool futuristic stuff we don’t yet have, like cities in outer space and flying cars. So Graham asks, Can we imagine today how the programming language that’s used for flying cars might look? And if we could, would we want to start using it right now?

Graham answers both questions affirmatively. We can imagine the hundred-year language and we want to start using it as soon as possible. So Graham sets out to design that language and put it to immediate use. The downside is the language might run slowly on today’s processors; the upside is, by not worrying about today’s limitations, it can be more elegant than contemporary languages, and it might also help inspire people to work even harder to develop faster processors. It might even bring about the existence of flying cars more quickly.

It’s easy to adapt Graham’s questions to libraries: Can we imagine the hundred-year library today? And if we can, would the people who currently rely on your library want to start using it? Would you want to work there? What’s keeping us from building it today?

Remember, if you read the Williamson Reports for the Carnegie Corporation, you’ll see that almost one hundred years ago Charles Williamson was able to draft the curriculum that’s still in use in library schools today. Actually, in many ways the recommendations he drafted would be an improvement on the library training provided to most librarians working in libraries today. For instance, he calls for greater standardization within curricula, for certifying library workers (his umbrella term for anyone who works in a library), and for better use of distance education, especially for professional development (what he refers to as “Training in Service”).

So just as Williamson could imagine and design the library training we’re receiving today, I think we can imagine the hundred-year library and begin designing that library now. I think the people who rely on your library today would be thrilled if it suddenly transformed into the library of 2112. And I think you would love to work there. Which is a good thing. Because in 2112 you will still be alive and you will still be working. Maybe at the library where you work today.

Why We Should Look 100 Years into the Future (part 2): Aubrey de Gray and Warren Buffett

You can view the idea that you will still be working in 2112 as preposterous. Or as a theoretical exercise. But at least one influential scientist, Aubrey de Gray, might see it as something of an understatement. de Gray is a biomedical gerontologist and the Chief Science Officer for the SENS Foundation, a California-based 501(c)(3) dedicated to combating the aging process. His bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. are from the University of Cambridge and he has been interviewed on “60 Minutes” and in the New York Times, and he has presented “A Roadmap to End Aging” at TED. He believes the science already exists to delay or even reverse much of what we view as the aging process. The idea is to stay alive long enough for science to eradicate each of the conditions that kill us.

Admittedly, this seems far-fetched, the idea of living another hundred or five hundred or thousand years. But consider that we’ve already eradicated many of the diseases that killed our ancestors. And there’s no lack of motivation to eliminate heart disease, cancer, respiratory diseases, stroke, and the other leading causes of death. In the last few decades, we’ve made tremendous progress in diagnosing and treating all of them.

Why does the possibility that we will be alive in one hundred years matter? It follows the same reasoning as Warren Buffett’s well known advice about investing: “An investor should act as though he had a lifetime decision card with just twenty punches on it. With every investment decision his card is punched, and he has one fewer available for the rest of his life.” (Warren Buffett, quoted in Mark Hulbert, “Be a Tiger, Not a Hen,” Forbes, May 25, 1992, p. 298) In other words, if you are personally invested in the long-term consequences of your actions, you make more rational decisions. It gets you away from the immediate gratification mindset and encourages you to think about first principles.

Which gets us to the central question of this essay: What will the library of 2112 look like? Which of our first principles will still apply? I think the core tasks and principles that have helped to define libraries since their founding will remain relevant for at least another hundred years. Libraries will continue to be about their users and their workers, about inquiry and intellectual freedom, about preserving the cultural record, about equalizing opportunity, and about cooperation.

So the first point I want to make is that libraries will still be about people. In fact, they’re going to be a lot more about people than they are today.

Libraries = You

Another way of saying that is, the hundred-year library is about “you,” Time magazine’s 2006 person of the year. Yes, you.

I first shared the thoughts in this article as a keynote at the Fall 2012 Tenn-Share Conference in Nashville, Tennessee. I could have done it via Skype or in a Google Hangout. I could have presented it as a webinar. I could have recorded my presentation and the attendees could have watched it together and discussed it, just like a lot of libraries do with recordings of TED talks. They could have waited until I published this article and discussed it online. The point is, there were essentially no technical barriers to their having the same discussion in collective isolation, or at least without the attendees and I being physically present in the same room at the same time.

Except that it wouldn’t have been the same discussion. We are social animals. We need each other, and not just emotionally. On a cognitive level, we get more information, and better information, from being in each other’s presence. In-person, human interaction is still the highest bandwidth way for us to communicate. And that’s not going to change in the next hundred years. That’s not how biology works.

So if this rather obvious point is correct, what are its practical implications? It means the hundred-year library, the library of 2112, is going to focus far more time, effort, and money on human interactions. Right now, the idea of signing up to check out a person is kind of a novelty. But I think libraries that have instituted these programs have the right idea. Libraries should serve as the focal point for meeting new people.

When we meet new people, we learn something. And if those interactions can have an empathetic, well planned out structure behind them, libraries could do an even better job of providing people with information about their community, their world, and any topics they’re interested in studying. I’m not just talking about public libraries: I think every library can better fulfill its mission by fostering more direct, in-person interaction.

The idea of high quality, high bandwidth, human interaction also argues that we might consider investing far, far more into what we currently think of as library programming. It would mean adapting our spaces to accommodate these changes. It would mean additional training for staff. It would mean learning more about what our neighbors and students and faculty want to know. The seeds are there, and a lot of libraries are already doing amazing work in this area. But what if we’re only just at the earliest stages of a movement?

To continue this idea, there’s no reason libraries can’t become the first thing people think about when they’re looking within their community or on their campus for activities that involve storytelling, visual art, and music. As with library conferences, the ability to digitize stories, visual art, and music hasn’t diminished our desire to experiences these things in person. When I look at representations of art, I want to see the original. When I hear mp3s of a band I like, I want to attend a live performance.

These impulses seem unlikely to change. If anything, we want more art, more scholarship, more experiences we can sample digitally and experience in person. The environment that fosters more art and scholarship is an environment that values and protects intellectual freedom, both for its producers and its consumers. Libraries will remain an important element within that environment.

Libraries = Intellectual Freedom

Libraries are already one of the leaders in intellectual freedom. We work hard to ensure privacy and freedom from censorship. But we’re not there yet. Exhibit A: our willingness to sacrifice our cardholders’ privacy in order to get the latest ebook bestsellers onto Kindles.

Here’s what I see for the hundred-year library. There’s an open source software project called Tor that allows people to surf the web anonymously, providing the highest level of intellectual freedom we can make readily available given the internet’s current structure. There are servers with Tor installed on them all over the world. To make use of them, you install client software onto your computer. Unfortunately, there aren’t all that many Tor servers, they only have so much bandwidth, and anonymizing web surfing isn’t as fast as serving web pages the regular way.

But there are an awful lot of libraries in this country and all over the world. They tend to be pretty well distributed geographically, and they tend to have a pretty fair amount of bandwidth. There’s no reason we couldn’t use that bandwidth for Tor, or whatever solution succeeds it. And there’s no reason we couldn’t install Tor software on our computers and teach library users to install the software on their computers. And because there’s no reason we can’t, and lots of good reasons we should, I figure there’s a pretty good chance it will happen.

So we can provide anonymous web access to anyone who wants it. Can we also provide internet access to everyone? One of the underappreciated aspects of the One Laptop Per Child initiative was the idea that each laptop could be a node on a wireless mesh network, enabling internet access to daisychain wirelessly from laptop to laptop. Mesh technology has come a long way since One Laptop Per Child was first proposed. Again, libraries tend to be pretty geographically dispersed. Think about what we could do with our own network, which we could connect to the rest of the internet, but only if we wanted. It wouldn’t be that hard to do, and it’s getting easier all the time.

Finally, I see libraries helping people to publish anonymously. Right now, it’s difficult to publish anonymously and it seems to be increasingly difficult to share our thoughts while also protecting our identity. Anonymity can be a touchy, scary topic. I think the positives on this one outweigh the negatives.

Libraries = Our Culture, Preserved

As long as we’re talking about helping people to publish, we should also talk about our traditional role of helping to organize the cultural record. I think it’s pretty obvious that each year there are more books, articles, and posts published than at any time in human history. And also more images, audio, and video. Libraries need to take a far more active role in helping to organize and preserve this material. In addition, we have a tremendous amount of material that’s yet to be digitized, and a tremendous amount that needs to be preserved.

I give Google credit for its ambition. We have a much better sense now about what’s involved in mass digitization efforts, and we have much better hardware and software, in part, as a result of the Google books project. We also need to acknowledge that Google plucked the low-hanging fruit. Books are typeset. They’re generally well cataloged. A huge percentage of the material that remains to be digitized and still needs to be preserved is lacking either or both. I’m talking about diaries and blueprints and hand-written medical records.

Think about the area where you live. There’s probably an area nearby with really pretty, really old houses? About how old are those houses?

When we look across the Atlantic, I think we can get a pretty good indication that those houses are still likely to be used as homes one hundred years from now. Maybe even five hundred years from now when you start to seriously consider retiring. The people who live in those houses five hundred years from now are going to be interested in learning about the people who lived in their homes before they did, the origin of their homes, and all the changes they’ve experienced along the way.

We have a lot of that kind of material in the library where I work, and probably in the libraries where you work as well. It’s really difficult to digitize, to make accessible, and to archive. I expect we’ll figure it out in the next hundred years.

Libraries = ≈

Just as it does today, the hundred-year library will continue to mitigate the effects of inequality. When I talk about the business that libraries are in, sometimes I say that we’re information coops. When I’m feeling a bit more frisky, I’ll say that we’re coops for low-cost, infrequently needed, durable goods. But when I’m feeling my best, I say we’re in the business of opportunity redistribution.

Fortunately for libraries, opportunity redistribution is in society’s collective best interest. We may want our kids to get in to the best school, but we want all the other kids to get in on their own merit.

So how do libraries redistribute opportunities? Helping to support education is obvious, and it’s going to continue to be important, but it’s not enough. Think about the things we’re fortunate enough to take for granted, but are comparatively inaccessible for huge swaths of our campuses and communities. I’m talking about museum passes, tickets to cultural events outside the library like movies, concerts, fitness classes, and music lessons. These things can be shared. So can tools, seeds, grafts for trees. Automobiles, even once they start driving themselves. Even once they start flying.

I’m interested in evidence of the most pressing needs, the ones where libraries can make the most difference. My guess is that it’s closely tied to students, especially younger students.

As with universities as a whole, and like doctors and hospitals, my guess is that libraries can create their own successful alumni and philanthropists, their own grateful patrons. Educating someone, saving their life, that’s it’s own reward. I don’t think colleges and universities or physicians do their work in order to collect donations later on. And I’m not suggesting libraries should, either. But I think if we help the people with the greatest need, if we change their lives, they’re going to succeed and they’re going to want to share that success with others by supporting the agencies that supported them.

Libraries = Cooperation

Most of the ideas I’ve discussed for the hundred-year library require interlibrary coordination, and I think every one that doesn’t require cooperation would benefit from it. Fortunately, cooperation is an area in which we excel. I’m pretty sure we could already use consortia for our consortia, and a hundred years from now, we’ll need consortia for our consortia of consortia.

And I’m all for it. As others have pointed out, if we got rid of ALA and started all over from scratch, what we’d create would look a whole lot like ALA. The same goes for OCLC. I figure what we really need, in addition to ALA and OCLC, is one or two or three more really big tent library organizations. Maybe that will be the Digital Public Library of America.

I don’t know what organizations will emerge, but I do know that if we’re going to set up mesh networks and provide anonymous access to everyone and digitize all the things that need digitizing and take a really thoughtful, evidence-based approach to diversifying and redistributing opportunity, we’re going to have to work together to do it.

Strategies

One strategy for helping us improve our ability to redistribute opportunity, and to operate more effectively in general, is to become more familiar with our history. Dr. Vann didn’t spend the 1950s studying the work of library education pioneers from Dewey through Williamson because their ideas seemed quaint or archaic. She studied them because she believed their ideas and experiences could help improve library education in the 1960s, 1970s, and beyond.

We also need to think about the truly long-term, which means believing that decisions we make now will affect us and those around us for a long, long time. For me, it’s easier to take that leap if I can persuade myself that I’m going to be here to experience all of the outcomes of the decisions I make. And by “experience” I mean not just that I’ll be using libraries a hundred years from now, but I’ll have to accept credit or blame for my actions and inactions. Aubrey de Grey may not be right about our life expectancy, but I see only upside in acting as though he is.

Which is one way of explaining Paul Graham’s work on his hundred-year language, which he named Arc. The project is ambitious, perhaps even megalomaniacal. Which may be why it works equally well to interpret it as a project based in altruism or as a project bred from selfishness. Whether his goal is to start a project that he’ll never himself get to finish or use in its realized form, or his goal is to use the best programming language on the planet even if he has to write it himself, his goal is to create something so spectacularly good that it will benefit everyone. As is clear from his essays and other writing related to Arc, he’s willing to fail, publicly, in its pursuit.

I hope libraries are ready to do the same. I hope we’re ready to work individually and together to identify the hundred-year library for ourselves. And I hope we’re ready to work publicly and without fear of failure to bring it about in a span far shorter than a hundred years.

References and Further Readings

Bobinski, G. S. (1986). Doctoral Programs in Library and Information Science in the United States and Canada. Library Trends, 34(4), 697-714.

Graham, P. Arc. Accessed November 14, 2012.

Richardson, J. V. (1982). The spirit of inquiry: The Graduate Library School at Chicago, 1921-51. Chicago: American Library Association.

Vann, S. K. (1971). The Williamson reports: A study. Metuchen, N.J: Scarecrow Press.

Williamson, C. C. (1971). The Williamson reports of 1921 and 1923: Including Training for library work (1921) and Training for library service (1923). Metuchen, N.J: Scarecrow Press.

This article is adapted from a keynote I delivered for Tenn-Share at the Nashville Public Library on September 28, 2012. It was also influenced by a chapter I wrote for Library 2025 (ALA Editions, 2013), edited by Kim Leeder and Eric Frierson. Thanks to Robert Benson and Kim Leeder for their help in turning a speech into an article.

Thanks for this Brett. Thought-provoking, and I think you have taken the key values of libraries (or what they should be valued FOR) and extrapolated them nicely into a future.

You leave me with a question, that may be best answered by others, using your article as a jumping-off point. If those of us who teach in library schools are teaching for the 1912 library, then what do we need to be specifically teaching for the 2112 library? Values, like those expressed in the article, we already do by the truckload through every unit we teach – if we are doing are job right.

It would be great to see library educators publicly discuss their thoughts on training librarians to work in the library of 2112.

As an apprentice library school educator (I’ve completed two years of PhD course work and I taught a library school course two summers ago), what’s most striking to me is how little evidence we collect about the academic achievements of the students we recruit and their relative success after graduation. Williamson recognized the importance of this data and did as much as he could to collect, analyze, and publish this information in his reports. Sadly, almost 100 years later, we still don’t consistently publish information about standardized test scores for library school applicants or matriculates, their undergraduate GPAs, our acceptance rates, students’ salaries before and after library school, or how long it takes graduates to find a job. We don’t have the sort of certification that Williamson advocates, and we haven’t come up with an alternative way to assess the knowledge students acquire in the pursuit of their degree. We have no useful longitudinal studies about the career arcs of graduates. We have a truckload of values, but the lawyers and the MBAs have actual data. Until we have something resembling empirical evidence, it’s difficult to believe that we’ll make any rational reforms. Even if we did, how would we know?

That said, I think the library of 2112 is going to require far, far greater understanding of technology than we typically impart. It’s not just that new librarians should be able to look at the Meadville Public Library in Pennsylvania and think, “That’s cool, they’re using open source software.” The goal should be for new graduates to be able to critique their choices and contribute to even better software than Meadville is currently using. I’ll know we’re headed in the right direction when the postings at jobs.code4lib.org are being filled by overqualified new library school graduates.

This post was well organized, educational, terrifying and inspirational. Now I’m curious what my library could be doing differently to prepare for 2113. I sincerely hope that, as our patrons’ lives became increasingly virtual, they will continue to be drawn to the library for a dose of old-fashioned, interpersonal togetherness; the rock concert illustration was fitting. Thanks for this!

Pingback : In The Library with the Lead Pipe | Blog & Twitter Investigations