Randall Munroe’s What If as a Test Case for Open Access in Popular Culture

Photo by Randall Munroe, What If. CC-BY-NC 2.5. Retrieved from http://what-if.xkcd.com/127/

In Brief:

Open access to scholarly research benefits not only the academic world but also the general public. Questions have been raised about the popularity of academic materials for nonacademic readers. However, when scholarly materials are available, they are also available to popularizers who can recontextualize them in unexpected and more accessible ways. Randall Munroe’s blog/comic What If uses open access scholarly and governmental documents to answer bizarre hypothetical questions submitted by his readers. His work is engaging, informative, and reaches a large audience. While members of the public may not rush to read open access scientific journals, their availability to writers like Munroe nevertheless contributes to better science education for the general public. Popularizers outside of academia benefit significantly from open access; so do their readers.

Open Access and the Public Good

Open access (OA) is a longstanding and important discussion within librarianship. As Peter Suber explains, the “basic idea of OA is simple: Make research literature available online without price barriers and without most permission barriers.” For a good grounding in the basics of open access, I refer the interested reader to Suber’s book Open Access; for a quick overview of open access, see this blog post by Jill Cirasella.

Open access has many benefits, both to academics and to the wider public. The benefits to academics are obvious: authors get wider distribution of their work, researchers at institutions with small budgets have better access to scholarly materials, and, for librarians, it represents a partial solution to the serials crisis.

In this article, however, I will focus on the benefit of open access to the public. When scholarship is freely available on the Web, it is available not only to scholars, but to anyone with an internet connection, the research skills to locate these materials, and the proficiency to read them. Open access has the potential to support lifelong learning by making scholarship available to people without any current academic affiliation, whether they are professionals in a field that requires continuing education, or hobbyists fascinated by a particular subject, or just people who are interested in many things and want to keep learning. In The Access Principle: The Case for Open Access to Research and Scholarship, John Willinsky describes the value of scholarly information to several specific segments of the public, including medical patients, amateur astronomers, and amateur linguists.

Both Suber and Willinsky cite critics who argue that most members of the public are not interested in reading scholarly articles or books, that the public cannot understand this material, or even that the information could be harmful to them. Suber criticizes the presumptuous attitudes of those who would make these claims, pointing out that the public’s demand for scholarly information cannot be determined until this information is made widely available. Willinsky objects strongly to the presumptuous attitudes of those who question the ability of the public to benefit from open access:

[P]roving that the public has sufficient interest in, or capacity to understand, the results of scholarly research is not the issue. The public’s right to access of this knowledge is not something that people have to earn. It is grounded in a basic right to know.

Willinsky’s argument for the public’s moral right to access scholarly research is both stirring and compelling. This is especially true for librarians, for whom access to information is a professional value.

Open access need not rely on any demonstration that the public has met some arbitrary threshold of interest and education. Without believing in a need for such proofs, I would nevertheless like to present one case illustrating how open access can benefit the public.

The public is, by its very nature, diverse. It includes the amateur and professional users of information cited above. The public also includes popularizers who can use open access scholarly literature in unexpected ways, not only to more widely distribute the fruits of scholarly research but also to create projects of their own. By looking at the role of one such popularizer, Randall Munroe, I will question two assumptions: first, that the public is so uniformly unsophisticated, and second, that they all need to read the open access literature in order to benefit from its wide availability.

What If

What If, a weekly blog that answers hypothetical questions using science and stick figure illustrations, is the work of Randall Munroe. Munroe is a former National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) roboticist but is better known as a webcomic artist. His primary project is popular webcomic xkcd, which explains itself with a disclaimer:

Warning: this comic occasionally contains strong language (which may be unsuitable for children), unusual humor (which may be unsuitable for adults), and advanced mathematics (which may be unsuitable for liberal-arts majors).

It would be fair to describe xkcd as a nerdy joke-a-day comic with stick figure art, but I should point out immediately that Munroe has often used it to explain scientific concepts. Notable comics include “Lakes and Oceans,” which illustrates the depth of the Earth’s lakes and oceans in a way that gives a better idea of their scope, and “Up Goer Five,” which uses the simplest possible vocabulary to explain how the Saturn V rocket works. Munroe’s science education agenda is thus visible even in xkcd.

The connection to science education is clearer in What If, in which Munroe uses real, scientific information to provide serious answers to ridiculous hypothetical questions posed by his readership, such as:

What if everything was antimatter, EXCEPT Earth? (“Antimatter”)

What would happen if one person had all the world’s money? (“All the Money”)

At what speed would you have to drive for rain to shatter your windshield? (“Windshield Raindrops”)

Munroe answers these questions using math, science, humor, and art. He pitches his answers appropriately to a smart and curious, but not necessarily scientific, audience. In fact, several questions have been submitted by parents on behalf of their children.

A good example is the first of the questions listed above: “What if everything was antimatter, EXCEPT Earth?” In about 500 words, Munroe covers the proportion of matter to antimatter in the universe, the solar wind, Earth’s magnetic field, the effect of space dust on the Earth’s atmosphere, and the dangers of large asteroids. This sounds like a lot of information, but with Monroe’s straightforward style and amusing illustrations, it is easy to read and understand.

Figure 1: An illustration from “Antimatter.” CC-BY-NC 2.5 Retrieved from https://what-if.xkcd.com/114/

So, What If is humorous and silly, but the questions are taken seriously, and in fact provide real scientific information. Having read this particular post, we know more not only about the prevalence of matter and antimatter, but also about the Earth, asteroids, and more.

What If is extremely popular. In 2014, Munroe published a book including some of the questions he’d answered in the blog along with some others which he felt deserved fuller attention. The book, the #6 overall bestseller on Amazon as of December 10, 2014, has been successful in reaching a large audience. While bestseller status is not necessarily an indicator of the book’s value, it does suggest that a high level of public awareness of this work.

Sourcing Information for Hypothetical Questions

As a guest on National Public Radio’s Science Friday, Munroe explained that What If is driven partially by his own desire to know the answers to the questions that people send him. He likes hypothetical questions, partly because “they’re fun,” but also:

A lot of the time it ends up taking you into exploring a bunch of weird questions or subjects in the real or practical science that you might not have thought about. (Munroe, “Interview”)

Through What If, Munroe uses research to explore questions and information sources. Munroe delves into many different types of sources in order to answer these questions.

Munroe’s sophistication as an information user manifests itself in his use of a wide variety of sources to answer many different kinds of questions. He uses Wikipedia as a starting point and YouTube as a useful source of visualizations, but he’s clearly familiar with a wide variety of ways to search the web and kinds of sources available there. He uses specialized web tools like Wolfram Alpha, a “knowledge engine” built to perform computations and provide controlled web searching. He takes advantage of online educational materials for the clarity with which they explain basic concepts and present mathematical formulae. He consults commercial catalogs to get the specifications on various products—unsurprising behavior for a former engineer! He consults blogs and enthusiast resources, such as amateur aviation and auto-repair sites, where there is a large and knowledgeable fan community. Amid this landscape, academic sources certainly have a place. They provide detailed information and a look at ongoing research, as I’ll discuss further below. Munroe’s frequent use of articles in ResearchGate and arXiv suggests that these repositories are also among his favorite sites.

Munroe’s teasing links to conspiracy sites also hint that he is well aware of the need to evaluate information for accuracy and confident in his ability to do so. He makes an effort to link to high-quality sites, although he has on one occasion (“All The Money”) admitted defeat (when trying to find the angle of repose for coins) and resorted to linking to a message board posting. Still, he carefully considers the information he uses; even when using a fairly standard resource like Google Maps, he looks carefully at the route it recommends. In “Letter to Mom,” he notes with surprise that Google Maps does not take advantage of the Buffalo Valley Rail Trail as a walking route and jokingly suggests it may be haunted. He also acknowledges other kinds of gaps in the information that’s available. His investigation into the amount of data storage available at Google (“Google’s Datacenters on Punch Cards”) works around the fact that Google does not disclose this information by looking into the cost of their data centers and the power that they consume.

In short, throughout What If, Munroe displays a high awareness of the information landscape and a strong ability to find, interpret, and appropriately deploy information, even though his information needs may be highly unorthodox.

Sources Used in What If

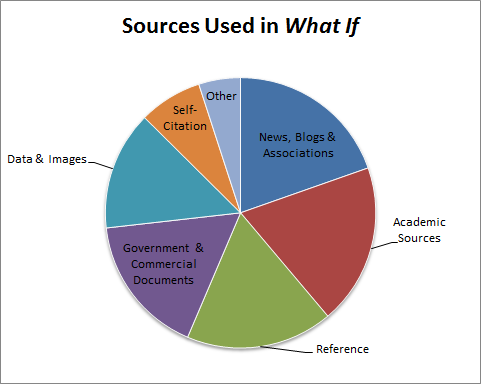

Since links serve as citations in the world of the web, I have gone through the entire run of the blog, which included 120 posts as of December 10, 2014, and analyzed the links.

This is an informal analysis; I examined and coded each entry but I have not done any validity tests on the categories. This chart is intended only to give an at-a-glance idea of the general types of sources Munroe consults.

Academic Sources include scholarly journal articles, books, and online course-related materials such as textbooks and slides.

News, Blogs, and Associations includes a wider variety of sources, but what they have in common is that they are written not for professionals or academics. Rather, they address either the general public or a specialized, non-professional community. Here I include news reports, blogs by experts, hobby sites, and so on.

Reference Sources comprise popular online reference sources, mostly Wikipedia but also the International Movie Database (IMDB) and similar sources.

Government and Commercial Documents often present analysis and scientific or technical information. NASA is the biggest source here, with many documents written by engineers.

Data and Images include charts, datasets, results from the online search engine/calculator Wolfram Alpha, videos, and so on.

Self Citation links lead back to other What If posts, to xckd, or to Munroe’s blog.

Other includes links to social networks, other webcomics, company front pages, and so on.

Sophisticated Use of Popular Online Information

Not all the sources Munroe uses are scholarly in nature. Of the source types listed above, three of them — Academic Sources, News Sources (etc.), and Government and Commercial Documents — might provide experimental or analytical information about the phenomenon of interest. This accounts for about half of Munroe’s citations. The remainder serve other purposes, such as reference, demonstration, or humor.

Munroe’s use of sources, including nonscholarly sources, demonstrates his sophistication and understanding of the internet. “Popular Reference Sources” is the largest category other than the three mentioned above; this category is dominated by Wikipedia, the most commonly-cited source in What If. Wikipedia is a commonly reviled source in academic contexts, but Monroe uses it in an appropriate and knowledgeable way.

Munroe understands that Wikipedia is a reference source, and generally points to it when introducing concepts with which his readers may not be familiar. In the antimatter example discussed above, Munroe links to the pages on Baryon asymmetry and CP symmetry when discussing the prevalence of matter and antimatter in the universe. By linking to these pages, he avoids unnecessarily introducing technical jargon into the main text of his article but still invites his readers to learn more about it. Most of his uses of Wikipedia are similarly definitional. Occasionally, they are playful, as in “Balloon Car”, where he breaks the word “catenary” into two links, one to the entry for “cat” and the other for “domestic canary.” Note that this moment communicates something about Munroe’s expectations for his audience; they are of course perfectly capable of both recognizing the joke and searching Wikipedia for the correct term (“catenary”) themselves. The links, then, are only a courtesy to readers. Notably, Wikipedia is not cited in the print book.

In fact, Munroe’s expectation that Wikipedia is a major part of his readers’ information landscape is so strong that he occasionally inserts the Wikipedia tag “[citation needed]” into his articles in an ironic, jokey way, when he takes for granted something that appears obvious. My personal favorite is in post “One-Second Day”, in which he remarks that the Earth rotates, inserts a “[citation needed]” tag and links to the famous conspiracy site, “Time Cube.”

His use of other popular online sources is similar; a good example is YouTube, to which he frequently links when he needs visual aids. In “Extreme Boating”, he links to several videos showing reactions with different substances through which he proposes rowing a boat.

Academic/Analytical Sources

Munroe is an information omnivore who constantly and intentionally mixes popular and scholarly, humorous and serious. Although he uses Wikipedia heavily for background information, he turns to deeper sources when more precise analysis is needed. His sources for this work include academic journal articles, and also government and commercial documents with scientific or technical content. However, the academic articles are of particular interest in a discussion of open access.

The post about antimatter is a good example. In it, Munroe’s links to Wikipedia links to Wikipedia are used to establish the basic concepts relevant to the question. Later in the post, questions come up that scientists still disagree about; here is where books and articles begin to be cited. The antimatter question leads to a discussion of just how much antimatter is in the universe and whether, for instance, antimatter galaxies could exist; this question is addressed with one scientific article that shows this has not yet been observed and another that proposes a new telescope to further examine the question. In other posts, many other questions are examined using similar sources. “Burning Pollen” cites a chemistry paper explaining the reaction between Diet Coke and Mentos in order to explain oxidation. “Laser Umbrella” cites several scientific articles about vaporizing liquids using lasers, as this question has often been studied. In “Speed Bump,” Munroe is working on a question about the fastest speed at which one can survive going over a speed bump, so an article in a medical journal about spinal injuries from speed bumps is useful.

As noted above, academic articles are not Munroe’s only source of scientific information. Articles from government agencies, particularly NASA, often serve a similar purpose. Munroe also often links to books, either by linking to a book’s record in WorldCat or Amazon, or by using Google Books to link a specific page, often one with a diagram or graph. What If also includes a few links (specifically, twenty-five of them) to educational materials such as class sites, lecture slides, and online textbooks.

For statistics and other kinds of quantitative information, Munroe often turns to other sites. Some of the government documents provide this sort of information, as do commercial entities such as rope manufacturers, cargo transporters, and so on. What If includes citations to data safety sheets and international standards, most notably in “Lake Tea,” which needs to cite standards for several different types of tea in order to answer a question about the strength of the brew made from dumping all the tea in the world into the Great Lakes. He uses Wolfram Alpha, the “computational knowledge engine” for calculations and conversions and Google Maps for locations and distances.

Contributions of Amateurs and Journalists

Finally, popular sources also have a place in What If. Munroe often links to news, professional and hobby associations, and blogs, both those produced by passionate amateurs and those used by professionals to connect to a lay audience. These include the New York Times and Slate, but also the popular Bad Astronomy blog, a visualization blog known as Data Pointed, aviation history enthusiast sites, and a linguistics blog by scholars at the University of Pennsylvania. In most cases, these are used because they provide specific, current information by knowledgeable people.

Thus, academic journals do not have a monopoly on useful scientific information. However, at 13% of all links, they comprise a substantial portion of Munroe’s research.

Open Access in What If

Munroe is aware of the open access movement; he has illustrated the available amount of open access literature (“The Rise of Open Access”).

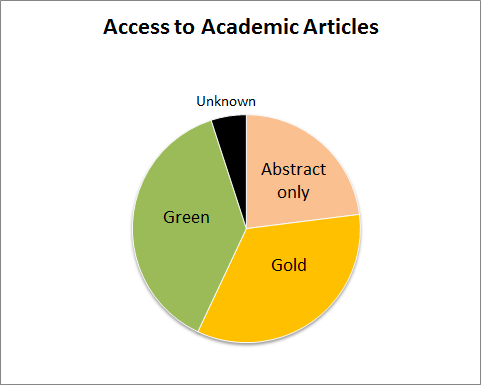

As of December 10, 2014, Munroe had referenced 100 academic articles in What If, and about 72 of them can be considered open access because their full text is freely available to the public in one way or another.

Within the Open Access movement, authors often refer to two ways to achieve open access—the “gold road” and the “green road.” Gold open access is provided by open access publishers who make their content freely available rather than using paywalls and subscriptions. Green open access is achieved when authors publicly archive their content online, with the permission of their publishers.1

For the purposes of this pie chart, anything that Munroe has linked from a repository or an author’s page is considered green open access, and anything linked from the journal’s website is considered gold open access. Because I am attempting to capture the perspective of a reader interested in a particular article rather than that of a publisher or librarian, I am ignoring some nuances important to open access advocates. In particular, I am counting all open access articles that are available through the publishers’ sites as “gold,” even including those which are available via hybrid models The hybrid model, in which subscription journals make some articles available to the public, contingent on author fees, does not support all the goals of the open access movement. However, it does make content available to readers within the journal itself so from a reader’s point of view, it makes sense to classify these articles as gold open access.

“Gold” and “green” open access were used about equally in What If (34% and 38%, respectively). “Gold” open access included some links to very well-known open access publications such as PLOS One, but also a wide variety of other journals and some conference proceedings. The “green” open access links were to repositories; arXiv, the open access repository of physics papers, appeared frequently, as did academic social networks like ResearchGate and Academia.edu, and of course, many university repositories and faculty websites. Munroe occasionally links to articles that are not freely accessible, including some from major publishers such as Nature, Springer, and Elsevier. For these articles, only the abstracts are available. These comprise 23% of the academic articles cited. This is a substantial proportion of all academic articles, but much smaller than the proportion of open access materials.

Why Open Access Matters to What If

Although Munroe occasionally links to an article that is not freely accessible, open access articles are preferable for obvious reasons. Munroe is a professional cartoonist, not an academic, so his profession does not automatically grant him access to subscription resources. Moreover, he cannot assume that his readers have access to any given closed-access resource. If Munroe succeeds in inspiring in his readers the kind of curiosity about the world that characterizes his own work, they will need resources that they are actually able to access. Open access is thus important to both the success and the quality of What If.

What If is an example of what can be achieved when information, and scholarly information in particular, is made readily available outside of academia. While Munroe depends on information from a variety of sources, the information he gleans from open access academic works is especially important because it connects him directly to the science.

Imagine a non-academic freelancer attempting to write a weekly column like What If in an environment in which all or most scholarly information is available only by subscription. Without academic affiliation, it is very difficult to obtain scholarly material in the quantity in which it is used in What If. To pay the access fee for each article needed would soon become prohibitive. Most current scholarly materials are not held in public libraries, many public libraries limit or charge for their interlibrary loans, and waiting for articles to arrive could affect the weekly publication schedule. Under such circumstances, it is not surprising that popularizers in the past have tended to be either academics or journalists, two professions which grant their practitioners access to information.

What If is driven by Munroe’s wide-ranging curiosity and that of his readers. What If began with the questions that xkcd readers sent to him; he found he too was curious about the answers. Because of the time he spent researching these questions, he decided to write them up and post them on his website. This is suggestive of the way that being an audience member sometimes works on the internet: Munroe’s readers felt sufficiently connected to him to send him these questions, and he felt sufficiently interested in the questions to research and respond to them. The ability to answer the questions to his satisfaction depends on the availability to both Munroe and to his readers of reliable information.

The Readership of What If

Munroe writes What If for a general audience. However, he believes that whether his audience is general or technical, “the principles of explaining things clearly are the same. The only real difference is which things you can assume they already know…” (“Not So Absurd”). Munroe expresses skepticism toward assumptions about general knowledge:

[R]eal people are complicated and busy, and don’t need me thinking of them as featureless objects and assigning them homework. Not everyone needs to know calculus, Python or how opinion polling works. Maybe more of them should, but it feels a little condescending to assume I know who those people are. I just do my best to make the stuff I’m talking about interesting; the rest is up to them. (“Not So Absurd”)

Munroe resists the idea that his audience needs to learn how to do the things that he knows how to do, like using good estimation techniques to understand the size of a number. Instead, he states that “the rest is up to them.” What If uses links according to this principle; anyone can understand the articles without reference to their sources, but the sources are nevertheless available for their reference.

The nature of What If as a question-and-answer site ensures that Munroe is always addressing at least one of his readers directly. Linking his sources, then, becomes part of the answer. Munroe does not simply dispense answers, rather, he encourages his readers to see where the information is coming from. Occasionally, he even makes comments on the things that he links, for example: “a positively stunning firsthand account” (“Visit Every State”), “one of the worst scanned pdfs I’ve ever seen” (“Enforced by Radar”), “a wonderful chart” (“Star Sand”), and so on. In one case (“All the Money”), he links to a book in Google Books and refers to a specific page so that a reader can find the information that he used. Like any citation, these links make it possible for a reader to consult the author’s sources. To a non-academic audience, however, citations are a meaningless gesture if they are not to open access resources. Thus, open access resources are important not only for Munroe to access his sources, but also so that he can share them with his readers. This attitude–that readers should be able to access cited sources in a click–contrasts strongly with that of open access critics who claim there is little public interest in scholarly works. Although in most cases it is not clear how many readers click through, YouTube videos linked from What If do see increased views; many commenters on such videos indicate that they arrived via links from What If.

Why What If Matters for Open Access

Why does it matter what resources are available to the author of a silly blog with stick figure illustrations? Although What If contributes to ongoing science education, the stakes are lower than they are for some of the other things that can be accomplished with open access, such as providing education and medical information to rural, underfunded, or poor areas.

I want to be clear that the purpose of open access is not only to benefit those who are highly educated, famous, and have a large platform of their own. I must also acknowledge that, as a white man on the Internet, Munroe’s path to popularizing scientific information is far smoother than that of others who do not share his privilege. However, I still think What If matters for open access, for several reasons.

First, scholarly information is sneaking into popular culture. What If shows how scholarly information can be relevant to people in their daily lives, even if they only use it to amuse themselves by thinking about unlikely scenarios. This increases the reach of scholarly research and contributes to public science education. There is interest in this information beyond a scholarly or professional context.

In the fields most of interest to Munroe, mathematics, physics, astronomy and earth and environmental sciences, open access has increased faster than most other fields (Bjork et al). Munroe relies on open access in a way that many humanities popularizers like Idea Channel’s Mike Rugnetta do not. However, as open access in the humanities increases, I hope to see projects that make use of it in interesting ways.

Second, What If has a very large audience. As of December 10, 2014, the book based on the blog was the #6 bestselling title on Amazon. Although many readers may never consult the book’s sources, they still benefit from their availability through the existence of What If. Munroe’s role here is that of a popularizer; he reads the scholarly literature that is relevant to his writing and produces something more accessible for the public. What If joins a host of science blogs in recontextualizing science for a different audience (Luzón). Popularizers have been writing since long before the beginning of the open access movement, but open access can make it much easier for popularizers to succeed, especially those who live outside of academia or journalism.

Additionally, although many readers might not click through the links in a What If entry to read the scholarly research that Munroe cites, those who are interested have the ability and the access to do so. What If mediates the information with accessibility and clarity, but because it exists as a born-digital work and because most of the links are to open access materials, readers are invited to examine Munroe’s sources.

Finally, Munroe and his readership stand as an example of a sophisticated, curious, and playful public who, although they may not be members of the scholarly community, have a strong interest in the work that is produced there.

Conclusion

To read What If requires the playfulness to put serious academic work to a silly purpose, the curiosity to learn about the universe in new and unusual contexts, and the sophistication to understand the larger information landscape from which all this proceeds. What If’s readers have the ability to understand the Wikipedia jokes, to have a basic awareness of the existence of both high- and low-quality information on the internet, and to integrate scholarly concepts into this larger landscape.

One of the most intriguing aspects of What If is its repurposing of scholarly information in ways unlikely to occur to more traditional popularizers with an explicitly educational mission. What If is not the work of an academic trying to produce more accessible information for the public; rather, it is the work of one member of the public putting academic work to use in a way that is meaningful for his audience. Munroe’s work draws on scholarly research, but it is markedly different from anything that we would expect to find in an academic context.

Given the success of What If, it is clear that there is a readership for unexpected reuses of scholarly information. Without open access, What If could not exist. As open access expands and the public finds its way to materials it did not previously have available, what other intriguing projects might we see?

Thanks to Hugh Rundle and Jill Cirasella, who pushed me to think through the things that were messy and unfinished in this article, and who asked lots of good, difficult questions. David Williams helped me with the images and Kelly Blanchat answered a copyright question for me. Thanks also to Steven Ovadia, for arranging the 2014 Grace-Ellen McCrann Lectures, at which an early version of this paper was originally presented, and to everyone who encouraged me to turn that presentation into an article.

References and Further Reading

Bjork, B. C., Laakso, M. Welling, P. & Pateau, P. “Anatomy of Green Open Access.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 64.2 (2014): 237-250. doi: 10.1002/asi.22963. Web. Preprint available at <http://www.openaccesspublishing.org/apc8/Personal%20VersionGreenOa.pdf>

Cirasella, Jill. “Open Access to Scholarly Articles: The Very Basics.” Open Access @ CUNY [blog]. May 18, 2011. Web. <http://openaccess.commons.gc.cuny.edu/about-open-access/>

–. Interview with Ira Flatow. Science Friday, NPR. 5 Sep. 2014. Web. <http://www.sciencefriday.com/segment/09/05/2014/randall-munroe-asks-what-if.html>

–. “Randall Munroe of xkcd Answers Our (Not So Absurd) Questions.” [Interview by Walt Hickey.] Five ThirtyEight, September 2, 2014. Web. <http://fivethirtyeight.com/datalab/xkcd-randall-munroe-qanda-what-if/>

–. “The Rise of Open Access.” Science 342.6154 (2013): 58-59. Web. doi: 10.1126/sciencef.342.6154.58

–. What If. Web. <http://what-if.xkcd.com>

–. xkcd. Web. <http://xkcd.com>

Luzón, María José. “Public Communication of Science in Blogs: Recontextualizing Scientific Discourse for a Diversified Audience.” Written Communication 30.4 (2013): 428-457.

Panitch, Judith and Sarah Michalak. “The Serials Crisis: A White Paper for the UNC-Chapel Hill Scholarly Communications Convocation.” Scholarly Communications in a Digital World: A Convocation. January 27-28, 2005. Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Web. <http://www.unc.edu/scholcomdig/whitepapers/panitch-michalak.html>

Suber, Peter. Open Access. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012. Web. <http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/open-access>

Willinksy, John. The Access Principle: The Case for Open Access to Research and Scholarship. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012. Web. <http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/access-principle>

- Many journals allow self-archiving by default, either immediately or after an embargo period. Other journals may agree to allow self-archiving after negotiation with the author. In some cases, journals allow authors to keep their copyright, so their permission is not required. [↩]

For more stories of users, both general public and academic, who benefit from OA, see: http://dash.harvard.edu//stories

Sorry, use this link instead: https://osc.hul.harvard.edu/dash/stories

Pingback : Editor’s Choice: Randall Munroe’s What If as a Test Case for Open Access in Popular Culture | Digital Humanities Now

Pingback : Latest Library Links 10th April 2015 | Latest Library Links

Pingback : Weekly Web Harvest (weekly) |

Pingback : Open Access Week 2015: A Roundup - Symplectic