No results found: A review of biographical information about award-winning children’s book authors in subscription and free resources

In Brief

Prompted by recent discussions of diversity and representation in children’s literature, this study evaluates resources recommended to students for author study assignments in children’s/young adult literature courses at one university. Striving to provide research materials that reflect the communities and experiences of students at The University of New Mexico—a Hispanic serving research university in a majority minority state—we were curious to see if information about children’s book authors from diverse backgrounds was available in free and subscription sources typically taught during one-shot instruction sessions. To identify strengths and gaps in the content provided by several resources, we examined coverage of authors who have recently received awards that recognize Indigenous authors and authors of color and/or authors who portray characters from a variety of backgrounds. While this study reviews only a sample of available author information, it can provide some knowledge regarding the depth and breadth (or lack thereof) of content available from these resources, which may help librarians responsible for children’s literature when sharing resource recommendations with their communities.

By Laura Soito and Sarah R. Kostelecky

Introduction

As librarians, we strive to meet the information needs of our communities and provide materials that are relevant to our users. However, this can be a challenge when users are searching for children’s literature, considering the documented lack of diversity and representation within children’s materials. Librarians responsible for children’s literature collections (at both public and academic libraries) must take the time to seek out materials written and illustrated by people who reflect the diversity of backgrounds and experiences of the communities they serve.

At The University of New Mexico (UNM), providing access to a variety of children’s books is a priority. UNM is one of a dozen universities that are both Carnegie Classified Research One and Hispanic-serving institutions (The University of New Mexico, n.d.-a) and is located in Albuquerque, the biggest city in the majority-minority state (New Mexico Department of Health, 2019; US Census Bureau Public Information Office, 2012). After Hispanic/Latino students, who comprise 42% of the student population, Native American students are the 2nd largest ethnic group on campus at 5% (The University of New Mexico Office of Institutional Analytics, 2019, p.14)—unsurprising as the state is home to 23 tribal nations. The College of Education is one of the largest colleges on campus (The University of New Mexico Office of Institutional Analytics, 2019) and multiple sections of the Children’s Literature course required for the Bachelor of Science in Education in Elementary Education are offered each semester (The University of New Mexico, n.d.-b).

Children’s literature collection development and use

As a result of the number of students studying children’s literature, Kostelecky, the Education Librarian, spends a great deal of time managing the collection and providing instruction in its use. To include a variety of materials in the collection, one strategy employed is the use of an approval plan to purchase award-winning and honor books. Those winning well-known awards (Newbery, Caldecott, Coretta Scott King) and less publicized awards (American Indian Youth Literature Award, Schneider Family Book Award) are purchased. Additional titles are added to the collection via patron requests and through traditional collection development activities by the Education librarian (e.g., reading book reviews, best of lists).

Instruction in use of the collection for UNM’s Children’s Literature course involves one session in the library where students are working on assignments to 1) locate books based on a theme and 2) find information about books and authors. Working from the UNM LibGuide for children’s literature, students follow along on their own computers and search the library catalog and subject specific databases including Children’s Literature Comprehensive Database (CLCD), EBSCO’s Education Research Complete, and Something About the Author Online [SATA]). The different types of content available (book reviews, literary criticism, classroom studies) and uses of these resources are discussed. The session ends with hands-on searching time using databases and a visit to the children’s section.

One specific assignment students receive in the UNM course is an author study. This involves researching a student’s chosen author, including the individual’s inspiration for writing, their background, and similar information. Author studies can be part of the curriculum for students studying children’s literature in K-12 and higher education settings (Elliott & Dupuis, 2002; Fox, 2006; Jenkins, 2006; Jenkins & White, 2007, 2007; Kennedy, 2012; Meacham, Meacham, Kirkland-Holmes, & Han, 2017; Moses, Ogden, & Kelly, 2015). To assist students searching for information about authors, instructors and librarians try to direct students to useful and high quality resources with this type of content. But which sources currently available will contain this information?

Based on Kostelecky’s experience, when students select more well-known authors, the library’s databases are sufficient for discovering author information. Yet these same resources were inconsistent in coverage of authors from non-dominant identities and Indigenous authors and authors of color. When looking for authors to highlight as examples during one-shot library sessions, Kostelecky had difficulty finding information across all sources about some authors she wanted to highlight (e.g. Nicola Yoon, Francisco X. Stork). Because the library included little to no information about these authors , what other sources could be recommended? If UNM Libraries purchase materials that are not useful to support students in these courses, should their subscriptions be continued?

These questions and experiences led us to conduct an initial exploration of the availability of author information found in both subscription and free resources. The author search list was built from recent award-winning authors from a variety of children’s and young adult literature awards and honor books. We hoped to gain an understanding of the strengths and gaps of different resources which include content about children’s book authors, paying particular attention to coverage of Indigenous authors and authors of color. While this study is only a sample, we believe it can provide useful information and highlight the strengths and gaps in commonly-used sources for researching children’s literature.

Literature Review

While the focus of this literature review is not centered on issues of diversity and representation in children’s literature, we recognize these issues as part of the context within which libraries function and support their users. The annually updated data on published children’s books about or written by Indigenous people and people of color from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center presents a good snapshot of the current publishing landscape. Of the 3,703 titles the organization reviewed in 2018, 778 or 21% were authored by Indigenous people and people of color and 1014 or 27% were about Latinx, African/African-American, Asian Pacific American and American Indian/First Nations people total (Cooperative Children’s Book Center, n.d.). This organization also recognized the contributions small and independent publishers made in 2018 towards increasing the numbers of diverse books available. Though the numbers of books by and about Indigenous people and people of color have generally increased since 2012, these numbers still could be improved upon as they do not currently reflect the diversity found in the U.S. overall (Maya & Matthew, 2019).

Supporting diversity in children’s literature

This continued lack of diversity in published materials has resulted in concerted efforts by individuals and organizations to highlight and make visible quality literature for children and young adults which represent the experiences of people across a range of ethnicities, backgrounds and cultures. For example, We Need Diverse Books (WNDB) is a nonprofit organization started in 2014 (Charles, 2017) that works to award and publish books by and about people of color. In addition to their book award, WNDB provides mentorships for authors, offers an app to help readers find books and edited a published anthology in partnership with a major publisher (We Need Diverse Books, 2017). There is also the blog American Indians in Children’s Literature by Nambé Pueblo scholar Debbie Reese which is a useful source to find recommended books by and about Native American/First Nations/Indigenous peoples. Reese thoroughly reviews and evaluates titles considering stereotypical imagery, misinformation and missed opportunities to share information about the history and culture of Indigenous people. These examples are just two of many resources that bring visibility to diverse literature for young people.

Selection and knowledge of diverse children’s books

While there are many resources to utilize to discover multicultural children’s books and quality children’s books overall, some studies have identified pitfalls that still limit teachers and librarians in choosing books to share with young readers.

One recent study (Fullerton et al., 2018) analyzed picture book recommendations made by professors and librarians knowledgeable about children’s literature for use in a new public library storytime space. The researchers analyzed the books chosen by the “expert groups” (as they term them), identifying characteristics of the recommended books and searching for patterns among the rationales for their selections. They found the award-winning status was a prominent factor in book selection for both expert groups (Fullerton et al., 2018, p. 88). Looking at ethnicity of the book authors among the title selections, 86% of the books librarians and 67% of the books professors chose were by white authors. Respectively, 20% and 39% of their chosen books featured main characters representing children or adults of color. (Fullerton et al., 2018, pp. 85-86). Interestingly, no books featuring LGBT characters or representing characters with disabilities were chosen. Both groups, librarians and professors, acknowledged the positive influence of awards, reviews and multicultural representation had on their book choices. This article emphasizes the important role librarians can play in recommending books to users. The study also illustrates why it is necessary for both librarians and professors to actively select and recommend books by and about underrepresented groups because people may not necessarily choose those materials without the conscious effort.

In a 2012 survey of preservice and inservice early childhood educators in Tennessee, Brinson found most participants were unable to identify children’s books with non-white characters (2012, p. 30). The author asked respondents to name two book titles featuring characters representing African-American, Latino-American, Asian-American and Native American ethnicities respectively, and they were unable to do so. While Brinson attributes the educators’ inability to identify diverse books to lack of preparation and exposure to multicultural literature as part of their coursework, it is not clear from the survey if this was the reasoning given by the respondents. However, it is still disheartening to be presented with the study results—that some educators working directly with young children are lacking basic awareness of diverse children’s literature.

Evaluating sources

Librarians and educators supporting patrons in any setting regularly evaluate a variety of resources to connect people with the most useful information. There are many options available to users researching children’s and young adult literature broadly. In the book Children’s Literature in Action: A Librarian’s Guide, Vardell (2014) identifies sources such as Something about the Author, Google, YouTube, Contemporary Literary Criticism, Contemporary Authors, Dictionary of Literary Biography, Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI), TeachingBooks.net, and JustOneMoreBook.com. Kruger (2012) conducted a content analysis to identify which subscription databases were accessible by school libraries across the country, categorizing databases by subjects including language arts. The resources available in the most number of states for this subject were NoveList in 12 states and Gale Books and Authors in seven states, with EBSCO Literary Reference Center in six states surveyed (2012, p. 13).

In a more general comparison of author biography reference sources, Soules (2012) compared coverage among two established library resources, Biography Reference Bank and Contemporary Authors Online, with Wikipedia and other web resources. Her findings show Wikipedia as the most current resource among the databases studied; it deals better with variant forms of names than the commercial databases, and the core content was found to be similar among resources, even though, as one would expect, each resource provided something unique. Wikipedia and the other web resources had a distinct advantage in being easily findable and free, whereas library databases may be less visible and available to users.

Methods

This study compares availability of information about recent award-winning children’s book authors within commonly used or recommended children’s literature reference sources.

The selection of award-winning authors to create our search list is based on multiple factors. First, UNM Library’s approval plan only includes award-winning (and some honor) book purchases; therefore, our library owns all the award-winning titles used for this study. Because award book lists are often recommended to students as a strategy to find quality titles, our approval plans support students by providing local access. Additionally, we thought there might be a higher likelihood of finding Indigenous authors and authors of color within the database sources if they had won an award; we hypothesized that more press and visibility from the recognition potentially would mean more content about them. Also, we chose to focus on award winners, assuming content providers would prioritize developing information about them as well.

The 11 awards we included in this study are the:

- American Indian Youth Literature Award – American Library Association (ALA) affiliate American Indian Library Association (AILA). Honors writing and illustrations by and about Native Americans and Indigenous peoples of North America. Biennial.

- Américas Award for Children’s & YA Literature – Consortium of Latin American Studies Programs. Awards authors, illustrators and publishers who produce quality children’s and young adult books that portray Latin America, the Caribbean, or Latinos in the United States. Annual.

- Asian Pacific American Award for Literature – ALA affiliate Asian/Pacific American Librarians Association (APALA). Awards work about Asian/Pacific Americans and their heritage based on literary and artistic merit. Annual.

- Boston Globe–Horn Book Awards – Horn Book Editor selected panel. Honors children’s/young adult literature published in the United States. Annual.

- Coretta Scott King Book Awards – ALA’s Ethnic & Multicultural Information Exchange Round Table (EMIERT). Honors books demonstrating an appreciation of African American culture and universal human values. Annual.

- Mildred L. Batchelder Award – ALA’s Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). Honors books originating in a country other than the U.S. and in a language other than English and translated into English for publication in the U.S. during the preceding year. Annual.

- Newbery Medal – ALSC. Awarded to author of the most distinguished children’s literature published in the United States. Annual.

- Pura Belpré Award – ALA affiliate REFORMA (the National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish-Speaking) and ALSC. Awards a Latino/Latina writer and illustrator whose work best portrays, affirms, and celebrates the Latino cultural experience in an outstanding work of literature for children and youth. Annual.

- Schneider Family Book Award – ALA. Honors author or illustrator for book that embodies an artistic expression of the disability experience for child and adolescent audiences. Annual.

- Stonewall – Mike Morgan & Larry Romans Children’s & Young Adult Literature Award – ALA’s Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Round Table (GLBTRT). Awards English language books that have exceptional merit relating to the gay/lesbian/bisexual/transgender experience. Annual.

- Tomás Rivera Book Award – Texas State University’s College of Education. Honors authors and illustrators who create literature that depicts the Mexican American experience. Annual.

For each award, names of authors, editors, and illustrators of award-winning books were collected from the awards website for the years 2013-2018. From this resulting list, six authors were identified as having won multiple awards and five the same award in more than one year (one author had received both multiple awards and the same awards more than once). Results associated with these authors have been deduplicated in the overall and award-specific counts.

We identified the sources to search based on our ability to access subscription resources as well as prior studies which searched for content using these same databases. We conducted author and illustrator name searches in late December 2018 using these reference sources:

- Something About the Author Online (SATA) is a Gale subscription database which presents biographical and autobiographical information about authors and illustrators for children and young adults. Beginning as a print resource in 1971, SATA now totals more than 300 volumes and is available both online and in print (“Something About the Author Online,” n.d.). SATA is an established reference source for libraries and was specifically recommended in Booklist for academic libraries that serve education and literature programs. (Bunch, 2009).

- NoveList is a subscription database with the primary purpose of supporting librarians with reader’s advisory service. It is a division of the EBSCO company and counts 25 librarians among its staff (EBSCO website). This study used NoveList K-8 Plus which offers reading lists and book reviews specifically for kindergarten to 8th-grade children (EBSCO website). This resource was accessed via the Albuquerque Public Library as UNM Libraries do not have a subscription, but the database is available to the community at large using a current public library card.

- GoodReads is a website which describes itself as “the world’s largest site for readers and book recommendations” (GoodReads website). Created in 2007 by husband and wife Otis and Elizabeth Khuri Chandler (website), the site was eventually acquired by Amazon. GoodReads is a well-known social media platform where users keep track of books they have read, discuss books and find book recommendations. A useful feature of the site relevant to users looking for author information are the author-created blogs and Q&A with site readers, though not every author utilizes these tools.

- Wikipedia is a free encyclopedia, with crowd-sourced content that has grown to over 5.8 million articles in English Wikipedia alone. Since its inception in 2001, it has grown to become one of the most accessed sites on the internet (“Wikipedia,” 2019). There are nearly 15,000 articles associated with WikiProject Children’s Literature, which is an effort to improve coverage of children’s and young-adult literature on Wikipedia.

To evaluate the presence of authors in SATA, author names were referenced against the most recent index at time of data collection (volume 334) and searched in the online interface. For NoveList, author names were searched using the “author” dropdown search box option. To search GoodReads we used the default keyword search box using the author’s name, which results in a list of books associated with that name. If the author’s name was listed, we clicked on their name, which led to an author page with some information. GoodReads authors were considered present if their profile contained more than their name, a title list, and metadata related to GoodReads membership. While some authors use blog and Q&A features, these were not considered as part of the profile.

The first pass of Wikipedia searching was conducted using links from the articles pertaining to these children’s book awards. Authors not found were then searched using the standard English Wikipedia search. All authors were also searched in Wikidata, a related free, crowd-sourced knowledge base, which provided verification of the English Wikipedia search results and helped to identify the presence of Wikipedia articles in languages other than English.

In addition, each author was searched in Google using the insert link feature in GoogleSheets. The nature of the top result was noted, and if the top result was not applicable to the author in question or duplicated by a source already considered in our study, a standard Google search was performed to identify the next available hit from the first page of results.

Results

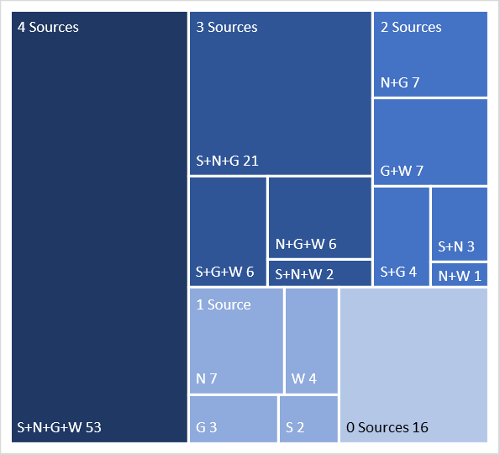

Overall, most award winners were found to have some biographical information available in the selected sources, though coverage varied by author. Of the 142 winners of the selected 2013-2018 awards, 126 (89%) were found to have coverage in at least one source, with 53 (37%) having coverage in all of the selected sources. See Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Reference source frequency combinations. The dark blue box represents authors found in all four of the sources, while the lightest blue represents authors found in none of the resources. Resources are represented by S= Something about the Author, N=NoveList, G=GoodReads, W=English Wikipedia. Frequency counts for each combination follows resource abbreviations.

Coverage varied both by award and resource. See Fig. 2. Authors were overall most likely to be present in GoodReads, with 140 (99%) of authors having a GoodReads profile and 107 (75%) of these profiles having more content than just names and title lists. Authors were least likely to be found in English Wikipedia with 79 (56%) authors having articles. Recent winners of the Batchelder Award were notably not found in English Wikipedia; however six of eight of the winners of this award had articles in other language editions. Overall, all winners of the Newbery Medal were found in all sources, while winners of the American Indian Youth Literature Award were most commonly omitted, with coverage ranging from 13-42% by source.

Figure 2: Proportion of 2013-2018 award winners present in selected biographical reference sources. Award and sources with highest proportion of coverage are displayed in blue, while pairs with the lowest coverage are displayed in red. GoodReads data represents entries containing more than minimal content.

| Award | Something About the Author | NoveList | GoodReads | English Wikipedia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Indian Youth Literature Award | 13% | 29% | 25% | 42% |

| Américas Award for Children’s & YA Literature | 82% | 73% | 91% | 45% |

| Asian Pacific American Award for Literature | 68% | 77% | 77% | 36% |

| Boston Globe–Horn Book Awards | 79% | 84% | 84% | 79% |

| Coretta Scott King | 67% | 67% | 100% | 100% |

| Mildred L. Batchelder Award | 75% | 88% | 63% | 0% |

| Newbery Medal | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Pura Belpré Award | 86% | 86% | 86% | 71% |

| Schneider Family Book Award | 82% | 82% | 100% | 68% |

| Stonewall – Mike Morgan & Larry Romans Children’s & Young Adult Literature Award | 70% | 70% | 100% | 80% |

| Tomás Rivera Book Award | 62% | 69% | 69% | 46% |

| All Awards | 64% | 70% | 75% | 56% |

Using general Google searches, it was possible to locate information about most authors. Searches most commonly returned a personal website (107), followed by sites provided by publishers, agents, or employers (11). Some searches returned other people, social media accounts, news articles, or cultural organization websites (such as from poetryfoundation.org) as the top results. Overall, four authors were not readily found by name using a Google search.

Considering depth of content, SATA and Wikipedia articles tended to be the most detailed, while NoveList and GoodReads were more likely to present brief facts with little to no narrative. SATA entries were consistently organized, with each article typically including sections with personal information, address, career, memberships, awards or honors, and a bibliography. Most articles contained a Sidelights section with a contextual description of the author’s life and works. In addition, SATA presented readers with a list of biographical and critical sources. Some articles contained photos of the authors or illustrations related to their work, or were followed by autobiographical narratives.

NoveList content focused on a description of works or writing style that could be helpful for reader’s advisory, such as when searching by theme or genre. The author entries frequently contained information about the author themselves (gender, ethnicity, and nationality) and characteristics of their works (i.e. tone, writing style, character portrayal). Of the authors with NoveList entries, only one quarter had narrative descriptions.

The information available in GoodReads entries was not consistent from one author to the next, with some entries containing no more than minimal name and title list information, to basic facts such as birthday, nationality, place of residence, a website, or social media handle, or a more detailed narrative description of the author and their works.

Like SATA, Wikipedia articles were usually more detailed and contained citations to external sources for more information. Article headers and content were not necessarily consistent but usually included information related to the author’s life (early life, personal life, education, career), awards/honors, and works. Some authors’ pages contained information about other careers, or information related to advocacy efforts, controversy, or censorship issues. Infoboxes in some articles summarize basic facts, such as birthdate, nationality, education, notable works, awards, or official website. Articles also provide links to authority control databases such as the Library of Congress Name Authority File and Virtual International Authority File.

Discussion

Highlight multiple sources

Based on this initial study, a good strategy for librarians supporting students researching children’s book authors includes instruction highlighting a variety of resources, both subscription and freely available, and the benefits and gaps of each. Libraries provide valuable information through subscription resources and often primarily direct users to them rather than to freely available sources, understandably, as we want to increase usage and justify their ever increasing purchase prices. Yet reviewing the results of the searches we conducted, these are not always the most relevant or useful sources for some types of information and content, like Indigenous author information. This reinforces the importance of emphasizing to students the use of multiple sources to gather information, especially for content about underrepresented people and communities.

While our study is exploratory, we found that GoodReads contained some content about almost all the authors; it is a source that would be useful for librarians to share with students for similar research. While Wikipedia often seems to rise to the top of results when searching for topics in daily life, here it was the least likely to have information about this particular set of children’s book authors. This is perhaps not surprising, given notability guidelines on Wikipedia that indicate need for secondary sources and our findings that content in these sources may also be lacking. Considering our initial results, library instructors may focus on activities where students navigate free and subscription resources and discuss the information needs each type may satisfy, thus applying the Searching as Strategic Exploration frame from the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.

Promoting the use of multiple sources could also bridge the transition between research as a student (when subscription databases are readily available) and research as a community member (since accessing paid content often requires travel/authentication/awareness of source). Acknowledging this access divide with students may surface new opportunities for them to learn research strategies and practice information evaluation across a range of sources with the benefit of librarian support. Discussion and activities to highlight this issue can introduce larger concepts of costs of information and ways information is controlled.

Help to close gaps

Our findings illustrate the varying impact of these book awards. The Newbery Medal is the most publicized and well known award which often translates into increased sales of the winning book and longer book circulation over time for winning authors (Kidd, 2007). This notability likely accounts for the 100% coverage of the Newbery-winning authors across all of our searched resources. Yet Newbery books are often critiqued for the lack of diverse authors honored (Yokota, 2011) though there has been some slight improvement in the last two years (Hertzel, 2018; Italie 2019). Ideally, all book awards would receive similar publicity and information resources provide broader coverage of all authors.

Libraries as organizations can work to improve visibility of a diverse range of children’s book authors and their publications. For instance, subject database and approval plan content gaps can be highlighted to vendors, clearly giving the message that content reflective of our diverse communities is required if our purchases are to continue. This is a way to leverage our organizational purchasing power to advocate for specific content development.

Individuals also have openings in which they can contribute information for others to use. We can see that many authors have been featured in SATA multiple times, and both GoodReads and Wikipedia provide opportunities for users to improve content. GoodReads users with 50 books in their libraries can apply for librarian status to edit book and author data, and GoodReads Authors are able to edit their own profile content. The author Q&A and blog features on GoodReads, while not formally part of an author’s profile, provide opportunities for students to connect with authors and dig deeper into the context of their writing.

Readers of Wikipedia are encouraged to click the edit button at the top of articles to contribute content. In addition, course instructors and librarians can develop assignments to engage students in contributing to Wikipedia. As examples related to children’s literature courses, students have worked on adding or improving articles about authors, banned books, and children’s book characters. Wiki Education provides a wealth of resources to support teaching with Wikipedia, including training materials, an assignment dashboard, and consultation. In our experiences, students have often found Wikipedia assignments to be more meaningful than simply writing a paper to be read by their course instructor.

Moving beyond Wikipedia, Allison-Cassin and Scott have recently shown how the related Wikimedia platform for structured data, Wikidata, can be leveraged to improve access to information about local musicians and Indigenous peoples and culture. Wikidata is fast becoming a top source for Linked Open Data and can be incorporated into other platforms, such as library catalogs, to support discovery and connection (Allison-Cassin & Scott, 2018; Smith-Yoshimura, 2018). Projects like these provide inspiration for anyone to improve the quality and availability of information about children’s book authors.

Conclusion

If libraries want to help students connect to a diverse range of authors and their works, they should not only consider what is included in library collections (print and digital), but also the resources that facilitate these connections. The study results make clear that finding information about authors often involves searching multiple resources. Even authors who have been recognized for their work via a book award can have limited content available about them across multiple reference sources. As we move forward, it is important to remember that information sources are not static and that we have opportunities not only to advocate for better coverage, but also to contribute incrementally to crowdsourced resources.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the time and effort given to improve this work by our peer-reviewer Michelle Martin, internal reviewer Amy Koester and publishing editor Ian Beilin. Thank you all for sharing your thoughts and knowledge with us.

References

Allison-Cassin, S., & Scott, D. (2018). Wikidata: A platform for your library’s linked open data. The Code4Lib Journal, (40). Retrieved from https://journal.code4lib.org/articles/13424

Brinson, S. A. (2012). Knowledge of multicultural literature among early childhood educators. Multicultural Education, 19(2), 30–33.

Charles, R. (2017, January 3). ‘We need diverse books,’ they said. And now a group’s dream is coming to fruition. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/books/we-need-diverse-books-they-said-and-now-a-groups-dream-is-coming-to-fruition/2017/01/03/af7f9368-d152-11e6-a783-cd3fa950f2fd_story.html

Cooperative Children’s Book Center. (n.d.). Publishing statistics on children’s books about people of color and First/Native Nations and by people of color and First/Native Nations authors and illustrators. Retrieved March 12, 2019, from Cooperative Children’s Book Center website: https://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp

Elliott, J. B., & Dupuis, M. M. (2002). Young adult literature in the classroom : Reading it, teaching it, loving it. Newark, Del. : International Reading Association.

Fox, K. R. (2006). Using author studies in children’s literature to explore social justice issues. Social Studies, 97(6), 251–256.

Fullerton, S. K., Schafer, G. J., Hubbard, K., McClure, E. L., Salley, L., & Ross, R. (2018). Considering quality and diversity: An analysis of read-aloud recommendations and rationales from children’s literature experts. New Review of Children’s Literature and Librarianship, 24(1), 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614541.2018.1433473

Hertzel, L. (2018, February 16). Bookmark: The Newbery and Caldecott – as well as the other ALA awards – are bringing recognition to diverse books. Star Tribune. Retrieved from http://www.startribune.com/bookmark-the-newbery-and-caldecott-as-well-as-the-other-ala-awards-are-bringing-recognition-to-diverse-books/474223993/

Italie, H. (2019, January 28). Meg Medina wins Newbery medal, Sophie Blackall the Caldecott. The Seattle Times. Retrieved from https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/meg-medina-wins-newbery-medal-sophie-blackall-the-caldecott/

Jenkins, C. B. (2006). “Did I tell you that you are the BEST writer in the world?”: Author studies in the elementary classroom. Journal of Children’s Literature, 32(1), 64–78.

Jenkins, C. B., & White, D. J. D. (2007). Nonfiction author studies in the elementary classroom. Portsmouth, NH : Heinemann.

Kennedy, A. (2012). Author studies: An effective strategy for engaging pre-service teachers in the study of children’s literature. Children’s Literature in Education, 43(1), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-011-9155-y

Kidd, K. (2007). Prizing Children’s Literature: The Case of Newbery Gold. Children’s Literature, 35(1), 166–190. https://doi.org/10.1353/chl.2007.0014

Krueger, K. S. (2012). The status of statewide subscription databases. School Library Research, 15, 1–23.

Maya & Matthew. (2019). Children’s books as a radical act. Retrieved April 8, 2019, from Reflection Press/School of the Free Mind website: http://www.reflectionpress.com/childrens-books-radicalact/

Meacham, S., Meacham, S., Kirkland-Holmes, G., & Han, M. (2017). Preschoolers’ author-illustrator study of Donald Crews. The Reading Teacher, 70(6), 741–746. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1579

Moses, L., Ogden, M., & Kelly, L. B. (2015). Facilitating meaningful discussion groups in the primary grades. Reading Teacher, 69(2), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1392

New Mexico Department of Health. (2019, January 31). Health indicator report of New Mexico population – race/ethnicity. Retrieved April 9, 2019, from New Mexico Department of Health, Indicator-Based Information System for Public Health Web website: https://ibis.health.state.nm.us/indicator/view/NMPopDemoRacEth.NM_US.html

Smith-Yoshimura, K. (2018, August 6). The rise of Wikidata as a linked data source. Retrieved March 25, 2019, from Hanging Together website: http://hangingtogether.org/?p=6775

Soules, A. (2012). Where’s the bio? Databases, Wikipedia, and the web. New Library World, 113(1/2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074801211199068

The University of New Mexico. (n.d.-a). The programs. Retrieved March 7, 2019, from http://www.unm.edu/welcome/about/programs.html

The University of New Mexico. (n.d.-b). UNM Catalog 2018-2019. Retrieved March 22, 2019, from http://catalog.unm.edu/catalogs/2018-2019/colleges/education/teach-ed-ed-lead-policy/undergraduate-program.html

The University of New Mexico Office of Institutional Analytics. (2019). The University of New Mexico spring 2019 official enrollment report. Retrieved from http://oia.unm.edu/facts-and-figures/oer-spring-2019.pdf

US Census Bureau Public Information Office. (2012, May 17). Most children younger than age 1 are minorities, Census Bureau reports. Retrieved April 9, 2019, from United States Census Bureau website: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-90.html

Vardell, S. M. (2014). Children’s literature in action: A librarian’s guide (2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=5301673

We Need Diverse Books. (2017, April 28). Our Programs. Retrieved March 21, 2019, from We Need Diverse Books website: https://diversebooks.org/our-programs/

Yokota, J. (2011). Awards in literature for children and adolescents. In S. A. Wolf (Ed.), Handbook of research on children’s and young adult literature. New York, NY: Routledge.

Appendix

Full Description of Figure 1

- 4 Sources

- 53 authors were found in Something About the Author, NoveList, GoodReads, and English Wikipedia

- 3 Sources

- 21 authors were found in Something About the Author, NoveList, and GoodReads

- 6 authors were found in Something About the Author, GoodReads, and English Wikipedia

- 6 authors were found in NoveList, GoodReads, and English Wikipedia

- 2 authors were found in Something About the Author, NoveList, and English Wikipedia

- 2 Sources

- 7 authors were found in NoveList and GoodReads

- 7 authors were found in GoodReads and English Wikipedia

- 4 authors were found in Something About the Author and GoodReads

- 3 authors were found in Something About the Author and NoveList

- 1 author was found in NoveList and English Wikipedia

- 1 Source

- 7 authors were found in NoveList

- 4 authors were found in English Wikipedia

- 3 authors were found in GoodReads

- 2 authors were found in Something About the Author

- 0 Sources

- 16 authors were found in zero sources

Pingback : WikiConference North America 2019: Reliability - Hanging Together