Racing to the Crossroads of Scholarly Communication and Democracy: But Who Are We Leaving Behind?

In Brief

Scholarly communication has tremendous potential to help build and sustain a democratic society. Nevertheless, in our race to the crossroads of scholarly communication and democracy, it is important to examine this work through the critical lens of broader librarian professional values—with particular attention to democracy itself, access, and diversity—to ensure that we are building systems that lead to true democracy for all. Using the feminist theory of intersectionality as inspiration, this paper builds on the talk I delivered as the Vision keynote speaker for the 2017 NASIG Conference and examines the crossroads of scholarly communication and democracy through the critical lens of librarian professional values, taking a close look at the ways in which these values intersect and interact to help ensure the race to the crossroads leaves no one behind.

Introduction

At the 2017 annual meeting of the North American Serials Interest Group (NASIG) held in Indianapolis, Indiana, home of the Indy 500, the theme centered on “Racing to the Crossroads” with a particular emphasis on scholarly communication and access to scholarly materials. Indeed, it seems that work in scholarly communication is racing to a crossroads. There have been any number of developments in open access, publishing, digital scholarship, cross-institutional and international collaboration, and so much more. Academic libraries are increasingly becoming involved in in-house publishing efforts, as well as collaborating with content providers to provide new tools and services to researchers at all points of the research lifecycle (Library Publishing Coalition, 2017; Pooley, 2017). Academic libraries are also playing increasingly vital roles in supporting all levels of institutional research: from brainstorming to literature reviews, to data collection and analysis, to drafting, to publication submission and self-archiving. As academia races to the crossroads of scholarly communication, libraries are clearly proving essential to this forward motion.

Nonetheless, with all this racing, it is important to pause and reflect, “Who is being left behind?” This reflection on who is being excluded from the forward motion in scholarly communication is of particular interest when considering where we are racing—to the crossroads—which brings to mind intersections of participation and identity. In fact, this reflection on intersections and exclusion is required if we are to examine the race in light of the role scholarly communication plays in promoting democracy and democratic involvement.

Intersectionality, Democracy, and Professional Values

In reflecting on crossroads and the intersection of democracy and scholarly communication, the theoretical framework of intersectionality naturally comes to mind. Intersectionality is a critical theory, developed by legal scholar and Black feminist Kimberlé Crenshaw, in which identity is viewed as a matrix of both oppression and domination (Crenshaw, 1991; Dhamoon, 2011). Any single individual is comprised, not of a single identity, but of a multitude of identities that carry their own privileges and oppressions. For instance, a person can be white and have race privilege, but also be working-class and bear the oppression of a classist, capitalist system. Intersectionality is a useful framework in which to examine library and information science work, particularly as it relates to the relationship between scholarly communication and democracy. When examining the race to the crossroads, intersectionality encourages us to think intentionally about intersections of identity and reflect on who is not participating in the race or who is being held up in traffic.

One way to guide this intersectional examination of the race is through the lens of our professional values, as expressed by the American Library Association (ALA) in its Core Values of Librarianship. This document, meant to be a codification of the “essential set of core values that define, inform, and guide our professional practice,” includes a set of concepts deeply relevant to a critical examination of our race to the crossroads of scholarly communication and democracy (ALA, 2004). These values—which include democracy itself, as well as access, diversity, education and lifelong learning, intellectual freedom, the public good, and social responsibility (ALA, 2004)—are themselves interconnected and embody intersectionality. It is not possible to pursue one without also seeking to pursue the others. For example, diversity cannot exist without a commitment to social responsibility and the public good, as systemic exclusion and oppression exist fundamentally within our society to impede the democratic inclusion of marginalized groups. Likewise, intellectual freedom and the ability to participate in the democratic process are meaningless without access because one can never fully engage with knowledge unless they have access to it. In so many ways, these vital professional values intersect in the race to the crossroads of scholarly communication and democracy. In this article, I will pay particular attention to the intersections of democracy, access, and diversity, as they are of particular relevance to the practice and potentialities of scholarly communication work.

Intersections With the Value of Democracy

There are many ways to examine how democracy, as a core value of librarianship and main thoroughfare in the intersection with scholarly communication, interacts with other values to ensure that no one is left behind in the race to the crossroads. It is important to note, however, that in looking at democracy as a value, we must be careful to start with true democracy for all, and not the democracy typically reserved for wealthy, literate, landowning white men that has been the foundation of American and other Western forms of democracy for centuries. If we are to take account for those left behind in the race to the crossroads of scholarly communication and democracy, we must engage in reflection that has veritable, inclusive democracy as its foundation.

As mentioned earlier, democracy intersects with intellectual freedom, as people need social, political, and physical agency to acquire knowledge in order to be able to engage meaningfully in the democratic process. In a related way, democracy intersects with the values of education and lifelong learning. Individuals must have access (another core value) to education and educational content in order to exercise intellectual freedom and engage in the self-determination of democracy. Essentially, developing and providing this educational content is a core function of scholarly communication work. There are many examples of scholarly communication facilitating the democratization of research and allowing more people, both within and outside the academy, to engage with subjects of enquiry. SciELO, an open access portal for scholarly publishing based in Brazil with ties throughout Latin America and beyond, has stood at the forefront of providing free and open access to knowledge. Likewise, African Journals Online (AJOL), “the world’s largest online library of peer-reviewed, African-published scholarly journals,” helps to ensure access to knowledge created on the African continent (AJOL, 2018). Both the Wellcome Trust, based in the United Kingdom, and the Gates Foundation, based in the United States, have recently released new public publishing portals, allowing researchers to showcase work, from failed experiments and null results to preprints of work housed in toll-access publications (Wellcome Trust, 2016; Mundel, 2017). Within the field of library and information science (LIS), the new Library and Information Science Scholarship Archive (LISSA) joins the long-standing and internationally renowned eLIS as a place for depositing open versions of LIS scholarship for public access. With these efforts and many more to provide public access to research, the democratization of research is becoming more and more of a reality.

In addition to empowering more democratic research, scholarly communication is enabling intersections of education and lifelong learning with the public good, yet another core value. Open Educational Resource (OER) initiatives are taking off at institutions across North America and around the world (SPARC, 2017; Open Education Consortium, n.d.). In some institutions, public education is becoming a priority in an attempt to bridge the “town versus gown” gap and bring more inclusivity to the academy. At the City University of New York (CUNY), chief librarian, Polly Thistlethwaite, and sociology professor, Jessie Daniels, created JustPublics@365, a series of open courses and workshops designed to bring the work of academia out to the surrounding community and vice versa (Daniels & Thistlethwaite, 2014). The courses included professors, formally enrolled CUNY students, local activists and community organizers, journalists, and community members, all gathered together to learn digital skills and the ways those skills intersect in the various work they all do; but more important, the course, characterized as a “Participatory, Open, Online Course” allowed participants to create and curate knowledge and contribute back to the scholarly and public conversation (Daniels & Thistlethwaite, 2014, p.4). As Daniels and Thistlethwaite (2016) note, “Being a scholar in the digital era means connection to the larger social world . . . It is now possible for scholars to connect their politically committed work to the world beyond the academy in ways that aim to make a difference” (p. 4). Through their work, Daniels, Thistlethwaite, and the staff at CUNY are making strides to include more voices and perspectives in academia to ensure that no one is left behind as they race to the crossroads of digital scholarship and learning.

Finally, democracy and access jointly intersect with intellectual freedom and social responsibility in ways to ensure that fewer and fewer are marginalized or left behind in the race to the crossroads. In its “Rights, Action, and Social Responsibility” initiative, the German publisher DeGruyter partnered with a number of university presses—including Columbia, the University of Toronto, Harvard, Princeton, and the University of Hawaii—to provide open access through the end of 2017 to more than 500 books and journal articles on key topics, such as constitutional history, climate change, truth and ethics, and immigration (Fallon, 2017). Director of the DeGruyter Publishing Partner Program, Steve Fallon (2017), writes, “Broadening access to this scholarship enables more people to address these issues in an informed manner: it helps us . . . to understand the struggles of all members of society.” Real democracy happens when everyone is able to gather at the intersection on equitable footing to learn about and discuss key issues; scholarly communication projects like those at DeGruyter, CUNY, the Wellcome Trust, and the Gates Foundation help to broaden the scope of democracy as a thoroughfare for intersecting with other core library values.

Intersections With the Value of Access

If democracy is the main thoroughfare of the intersecting crossroads, then access is a key side street that both intersects with and enables democracy and other core values. Indeed, access generally, and open access in particular, are hallmarks of scholarly communication work and the role it plays in building a democratic society. Questions of access are also essential to engaging in self-reflection, as a profession and a society, on issues of exclusion—that is, in recognizing who has access to participate in democracy, in scholarly publishing, in public discourse, and who does not. Librarian and historian Robert Darnton (2012) notes, “The history of libraries has a dark side. Far from demonstrating uninterrupted democratization in access to knowledge, it sometimes illustrates the opposite: ‘Knock and it shall be closed’” (p. 2).

As discussed earlier, access is essential to the value of intellectual freedom, as individuals cannot engage with knowledge unless they have access to it. Access also, along with democracy, intersects with the public good and social responsibility. The public cannot enjoy the fruits of the democratic process without access to the knowledge on which that process is based. Projects like JustPublics@365 at CUNY or the “Rights, Action, and Social Responsibility” initiative at DeGruyter are meaningless without public access for everyone to engage with the relevant learning and research. This access becomes even more crucial when the knowledge material in question has been created by members of marginalized communities, who often do not have access to the ivory towers and research bastions in which their content may be locked. Access is vital to true democracy that provides equitably to all, a democracy that goes beyond the systemic oppression and exclusion that marks modern Western democratic principles.

In addition to intersecting with the public good and social responsibility, open access can also enable democracy through the promotion of diversity. It is important to note, however, that open access only has the potential to amplify diverse voices and perspectives but does not do so automatically without intentional action to dismantle systems of exclusion (Hathcock, 2016). As Charlotte Roh (2016) writes in her article on library publishing and diversity, “Library publishing [via open access] allows new voices to find their way into the disciplinary conversations, reach new audiences, both academic and public, and impact existing and emerging fields of scholarship and practice in a transformative way” (p. 83). One example of this potential broadening effect of access is a recent Mellon grant to the University of Arizona Press to republish out-of-print Indigenous and Latinx studies texts as open access monographs (University of Arizona Libraries, 2017). This Mellon grant of $73,000 to open up such foundational cultural texts comes at a time when the state of Arizona recently lost an ongoing legal battle over its attempt to ban ethnic studies from K through 12 public schools (University of Arizona Libraries, 2017; Harris, 2017). As University of Arizona Libraries’ Dean Shan Sutton explains, “I hope that by promoting a deeper understanding of how our shared history influences our world today, we can be a catalyst for broader recognition of how diverse communities and cultures are a foundation of the American experience” (University of Arizona Libraries, 2017). Similarly, the U.S. Library of Congress, newly under the direction of Carla Hayden, pursues work on its National Digital Initiatives to “expand the use of” and access to the American cultural patrimony curated and preserved in its collections (Library of Congress, n.d.). Both the Library of Congress and the University of Arizona Libraries are intentionally and conscientiously working to improve access to materials so that no one is left behind in the race to the crossroads of democracy.

Nevertheless, it is important, when examining the value of access, to bear in mind that true access involves so much more than posting material online. As Daniels and Thistlethwaite (2016) acknowledge, “The conditions that constrain attention to some ideas and support attention for others cannot be addressed with technology alone; they require social and political adjustments” (p. 118). In the realm of open data, software developer and educator Jer Thorp posits five criteria for the designation of truly open data. Thorp (2016) argues that data are not open merely because they are posted online for free, public access, that what we have now is largely no more than “open-ish data, openesque data at best.” To create data that are “actually open,” they should also be made accessible in other key ways, such as making them available in multiple languages or providing understandable documentation, to avoid shutting some users out of access (Thorp, 2016). In the realm of open educational resources, educators and open pedagogy leaders Robin DeRosa and Maha Bali both advocate the importance of acknowledging and correcting for the digital divide when providing open resources to students (DeRosa, 2017, “Costs and Access”; Bali, 2017). They note that those most in need of open educational resources may not have the technological skills or infrastructure to access it. With this consideration in mind, the Foundation for Learning Equality works to bring open educational resources to countries and regions lacking the infrastructure to access these resources on their own. Similarly, the Wikimedia Foundation (2018) and the Swiss open source company Kiwix are working to provide global offline access to Wikipedia and other Wikimedia sites. It is through the critical work of the Foundation for Learning Equality, DeRosa and Bali, Thorp, Wikimedia, and others that inequities in access can be dismantled to ensure true democratic participation for all.

Intersections With the Value of Diversity

One other key side street in the crossroads between scholarly communication and democracy is the core value of diversity. In many ways, diversity exists as the most important and pressing value in the race to the crossroads of democracy and scholarly communication. Diversity forces us to take a critical look at our tools, practices, services, and other values to address that vital question asked at the beginning of this article, “Who is being left behind?” Following the path of diversity as a core value also encourages us to reflect on other related questions, essential to ensuring true democracy and access to information for all: Whose voices are being heard? Who is privileged with access? Who is at the forefront of democracy? Who benefits most from the “public good” or “lifelong education”? In essence, the value of diversity interacts with and empowers work both within and through all of the other core values of our profession.

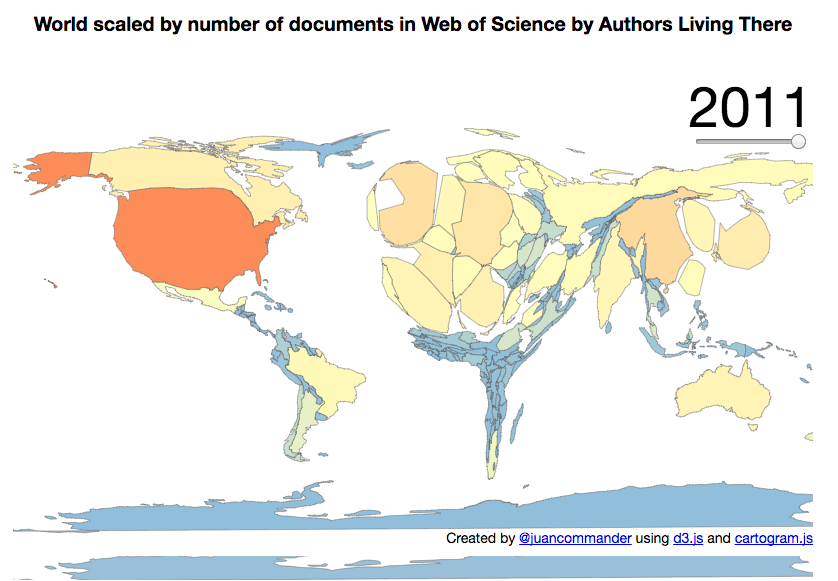

Addressing issues of diversity demands that we engage with key reflective questions like the ones above, lest we end up with exclusionary products and practices that privilege democratic participation of some over others. A particularly unfortunate example of this lack of reflective interrogation in the race to scholarly communication lies in a recent special Black Lives Matter issue of the Journal of Political Philosophy that failed to include a single black contributing author, or any author of color for that matter (Goldhill, 2017). The all-white journal issue, which focused on issues of importance to black communities and other communities of color, was merely one of a long line of issues that solely featured the voices and perspectives of white philosophers (Goldhill, 2017). In their race to participate in an ongoing social discussion, the editors of the Journal of Political Philosophy never stopped to question who was being left behind or whose voices were being excluded. Likewise, on a more global scale, similar failures to engage in critical interrogation of diversity issues surfaces in the ways scientific citations are indexed and cataloged. In his map scaling the continents of the world based on citations indexed in Clarivate Analytic’s Web of Science, a widely recognized science citation index, Juan Pablo Alperin (2011) strikingly demonstrates how the work of certain world regions is privileged over that of others (Image 1).

Image 1. Scaled map of the world based on location of Web of Science authors by Juan Pablo Alperin using CartoDB.

Asia and Africa, the two most populous continents on the planet, are mere slivers of their representative sizes, whereas North America and Europe are highly enlarged with the number of their representative citations. The scientific work being done on the Asian and African continents are largely underrepresented in Web of Science, while publishing priority is given to the work of North American and European researchers.

These examples demonstrate the ill-effects of failing to account for diversity in the race to the crossroads of scholarly communication and democracy. These acts of erasing marginalized knowledge from the scholarly record not only affect the nature of research and knowledge today but provide very skewed dominant narratives to knowledge seekers of the future. Nonetheless, there are ways to intentionally bring diversity into the intersectional mix. For example, the Mellon Foundation recently awarded over half a million dollars to the Association of American University Presses (AAUP), along with the presses at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), University of Washington, Duke University, and the University of Georgia, to develop diversity residencies for members of underrepresented groups interested in working in academic publishing (Association of American University Presses, 2016). This Mellon grant to diversify scholarly publishing comes at a time when it could not be needed more; as Alice Meadows noted at the 2015 meeting of the Society for Scholarly Publishing (SSP), “There’s a problem with racial diversity overall in terms of representation. There’s a teeny tiny number of ethnic minorities working in scholarly publishing; it’s terrible” (Cochran et al., 2015). Similar diversity programs exist in LIS with the aim of bringing more members from underrepresented communities into the profession, including programs such as the Association of Research Libraries’ (ARL) and Society of American Archivists’ (SAA) Mosaic Program, the ALA Spectrum Scholarship Program, and the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Diversity Alliance.

On a more global scale, organizations like Force11 are working to build a Scholarly Commons, a group of communities unified by a set of principles geared toward building more open and accessible scholarship, with a particular focus on ensuring that the Commons represents a global and inclusive collective of scholarly communities (Force11, 2017). Each of these efforts to promote diversity in the race to the crossroads of scholarly communication and democracy help to build a more representative scholarly community in the service of true democracy. Essentially, racing to the intersection means nothing if, when we arrive, we see only the same faces.

Moving Forward

Scholarly communications has tremendous potential to help build and sustain a democratic society. Nevertheless, in our race to the crossroads of scholarly communication and democracy, it is essential that we engage critically with our professional values—with particular attention to democracy itself, access, and diversity—to ensure that we are building systems that lead to true democracy for all. Our goal should be to build what archival scholars Michelle Caswell, Ricardo Punzalan, and T-Kay Sangwand (2017) describe as “real democracy,” where power is distributed more equitably, where white supremacy and patriarchy and heteronormativity and other forms of oppression are named and challenged, where different worlds and different ways of being in those worlds are acknowledged and imagined and enacted” (p.6).

Thus, the race forward to the crossroads of scholarly communication and democracy should inevitably involve frequent “rest stops” for critical introspection and reflection, stops to lend transportation (perhaps public transportation) to those left behind or to clear away roadblocks for others, and even detours into new and unexpected areas. As library dean Lareese Hall (2017) notes, “It is in the places of intersection that real change and magic happen” (para. 10).

I’d like to extend heartfelt thanks to my internal reviewer, Sofia Leung, my external reviewer, Megan Wacha, and my publishing editor, Annie Pho, for your friendship, solidarity, and work in making this article so much stronger than I could’ve made it on my own. You are amazing, powerful women who make my “race” so much smoother.

References

African Journals Online. (2018). African Journals Online: Home. Retrieved from https://www.ajol.info.

American Library Association. (2004). Core values of librarianship. Chicago, IL: Author. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/corevalues.

Alperin, J. P. (2011). [Interactive web-based map]. World scaled by number of documents in Web of Science by authors living there. Retrieved from http://jalperin.github.io/d3-cartogram/.

American Association of University Presses. (2016). AAUP member presses to launch diversity fellowship [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.aaupnet.org/news-a-publications/news/1395-aaup-member-presses-to-launch-diversity-fellowship.

Bali, M. (2017, April 5). Keynote: Maha Bali – Hiding in the open [Video file]. Retrieved from https://oer17.oerconf.org/sessions/keynote-maha-bali/#gref.

Caswell, M., Punzalan, R., & Sangwand, T. (2017). Critical archival studies: An introduction [Editors’ note]. Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 1(2), 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.24242/jclis.v1i2.50.

Cochran, A., McNamara, S., Michael, A., Tissenbaum, M., Meadows, A., & Kane, L. (2015, May 29). Mind the gap: Addressing the need for more women leaders in scholarly publishing [Video file]. Retrieved from https:// youtu.be/sDS0lWz7lNU.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299.

Daniels, J., & Thistlethwaite, P. (2016). Being a scholar in the digital era: Transforming scholarly practice for the public good. Chicago, IL: Policy Press.

Daniels, J., & Thistlethwaite, P. (2014). Engaging academics and reimagining scholarly communication for the public good. New York, NY: The Graduate Center at CUNY. Retrieved from http://library.gc.cuny.edu/themify/wp-content/uploads/JP365%20Report%20Final%20031014.pdf.

Darnton, R. (2012). Digitize, democratize: Libraries and the future of books. Columbia Journal of Law & Arts 36(1), 1-19.

DeRosa, R. (2017, January 22). Extreme makeover: Pedagogy edition [Blog post]. actualham: the professional hub for Robin DeRosa. Retrieved from https://robinderosa.net/higher-ed/extreme-makeover-pedagogy-edition/

Dhamoon, R. K. (2011). Considerations on mainstreaming intersectionality. Political Research Quarterly 64(1), 230-243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1065912910379227.

Fallon, S. (2017). Rights, action, and social responsibility. Retrieved from https://www.degruyter.com/page/1419.

Finnell, J., & Hall, L. (2017, March 8). Nothing tweetable: A conversation or how to “librarian” at the end of times. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. Retrieved from https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2017/nothing-tweetable-a-conversation-or-how-to-librarian-at-the-end-of-times.

Force11. (2017). WP1: Self critique. Retrieved from https://www.force11.org/group/scholarly-commons-working-group/wp1-self-critique.

Goldhill, O. (2017, May 27). Philosophers published a “Black Lives Matter” series written entirely by white professors. Quartz. Retrieved from https://qz.com/992782/philosophers-published-a-black-lives-matter-series-written-entirely-by-white-professors.

Harris, T. (2017, August 23). Arizona ban on ethnic studies unconstitutional: U.S. judge. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-arizona-education/arizona-ban-on-ethnic-studies-unconstitutional-u-s-judge-idUSKCN1B32DE.

Hathcock, A. (2016, October 6). Open access keynote [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5_7SXNW-5DQ.

Library of Congress. (n.d.). National digital initiatives. Retrieved from http://digitalpreservation.gov/ndi.

Library Publishing Coalition. (2017). Library publishing directory. Atlanta, GA: Author. Retrieved from https://www.librarypublishing.org/resources/directory/lpd2017.

Mundel, T. (2017, March 24). Another step forward in making scientific data available for everyone [Blog post]. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@trevormundel/another-step-forward-in-making-scientific-data-available-for-everyone-febe9bcf8e7e.

Open Education Consortium. (n.d.). About the Open Education Consortium. Retrieved from http://www.oeconsortium.org/about-oec.

Pooley, J. (2017, August 15). Scholarly communications shouldn’t just be open, but non-profit too [Blog post]. The London School of Economics and Political Science Impact Blog. Retrieved from http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2017/08/15/scholarly-communications-shouldnt-just-be-open-but-non-profit-too.

Roh, C. (2016). Library publishing and diversity values: Changing scholarly publishing through policy and scholarly communication education. C&RL News 77(2), 82-85. Retrieved from http://crln.acrl.org/index.php/crlnews/article/view/9446/10680.

SPARC. (2017). Open Education. Retrieved from https://sparcopen.org/open-education.

Thorp, J. (2016, October 5). Open for who? [Blog post.] Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/memo-random/open-for-who-ce698a8de79c.

University of Arizona Libraries. (2017, April 10). Grant supports creation of open access humanities books. UA News. Retrieved from https://uanews.arizona.edu/story/grant-supports-creation-open-access-humanities-books.

Wellcome Trust. (2016, July 6). Wellcome to launch bold publishing initiative [Press release]. Retrieved from https://wellcome.ac.uk/press-release/wellcome-launch-bold-publishing-initiative.

Wikimedia Foundation. (2018, July 18). Wikimedia Foundation and Kiwix partner to grow offline access to Wikipedia [Blog post]. Wikimedia Blog. Retrieved from https://blog.wikimedia.org/2018/07/18/wikimedia-foundation-and-kiwix-partner-to-grow-offline-access-to-wikipedia/.

Pingback : Racing to the Crossroads of Scholarly Communication and Democracy: But Who Are We Leaving Behind? – The Idealis

Pingback : Racing to the Crossroads of Scholarly Communication and Democracy: But Who Are We Leaving Behind? – In the Library with the Lead Pipe – Scholarly Communication at Scale

Pingback : The SCOOP: Open Access Week 2018: Ensuring Open Access is Equitable and Inclusive | ATLA Newsletter

Pingback : Reading That Inspired Me In 2018 – Krista McCracken